This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

2th October 1263 – The Battle of Largs, in which the Kings of Scotland decisively defeat the Norwegians, leading to the Scottish capture of the Western Isles

In the declining years of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries, the British Isles came under repeated attack from various peoples from Scandinavia.

The most successful of these were the Angles and Jutes who, along with the Saxons from North Germany and the Frisians from the Netherlands, managed to settle the largest most prosperous part of the British Isles, that being what we today call the lowlands of Scotland and England.

The next great wave of Scandinavians began to arrive after 793 when a group of Danes sacked the monastery of Lindisfarne in northern England.

For the next 100 years raids, trading expeditions and invasions steadily increased across Britain and Ireland. In the mid-800s, Scandinavians, mainly from Norway and Denmark, began to settle the British Isles. They established settlements in Ireland, most notably Dublin, heavily colonised the north-eastern part of England and the Northern and Western Isles of Scotland.

Eventually most of these Scandinavian settlers would integrate into the local communities or swear allegiance to the local kings. The major exception to this was the Western Isles of Scotland, which continued to be inhabited by Norwegians who swore allegiance to the Kings of Norway rather than the Kings of Scotland. Originally these were independent settlers, but during the 1100s the Norwegian kings managed to get these people to swear fealty to them.

The Western Isles of Scotland are cold and windswept, and have numerous inlets and tiny islands. This geography perfectly suited the Norwegians, who were masters of the sea, and whose native Norway is similar, with its many fjords.

By the start of the 13th century, the kingdom of Norway was a sprawling kingdom spread across the North Sea. The king had as his vassals the lords of the islands of the Faroes, Shetland, Orkney, Hebrides, the Isle of Mann, Iceland and the two small Norse settlements in Greenland (These would die out during the Bubonic Plague and not be restored for centuries.)

By the 13th century, Scotland had been through many changes over the preceding few centuries, changes which are poorly understood due to the lack of written sources in this period. The Pictish people who once ruled modern Scotland had disappeared, possibly being absorbed into the Anglo-Saxon and Gaelic peoples. From this cultural mix emerged a new identity, that of the Scots.

During the 9th century, the two major kingdoms of the northern British Isles had united to form the Kingdom of Scotland, or Alba as it was sometimes known. Scotland would conquer the Anglo-Saxons in the lowlands and even northern England for a brief time. During the 11th century Normans, who had conquered the Kingdom of England to the south, began to appear more often in the Scottish nobility. These Scoto-Normans would come to rule over Scotland in the 12th century.

For the first half of the 13th century, the Scots increasingly consolidated their kingdom, centralising power and adopting a style of kingship more like that of the Anglo-Normans and French.

Part of this reform was the efforts of the Scottish crown to bring all the Norwegian-controlled regions in western Scotland under their control.

In 1249, the Scottish King Alexander II offered King Haakon of Norway, a payment in return for the Norwegians ceding control of the Western Isles to them. This was rejected and so Alexander invaded the Western Isles and nearly captured them for the Scottish Crown. He died suddenly on 6 July, passing the throne to his 8-year-old son Alexander III.

As was so often the case in Medieval kingdoms, when the throne passed to a child the kingdom would be embroiled in serious internal strife. The invasion of the Western Isles disintegrated upon the king’s death and Scotland was plunged into internal chaos as various regents fought for control over the young king.

When Alexander was finally declared a full adult at the age of 21 in 1262, he immediately began to make preparations to finish his father’s conquest of the Western Isles. Initially he followed his father’s plan of buying the islands but once again this was rejected.

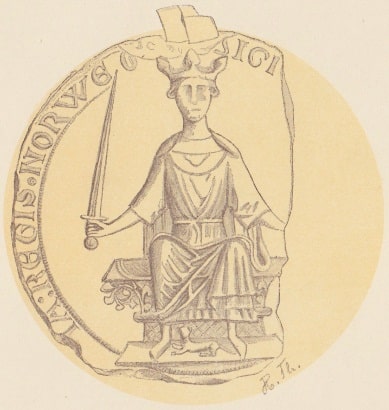

News of the Scottish intentions prompted the Norwegian King Haakon to assemble a huge fleet of warships and set sail for Scotland to repulse the Scottish invasion. In the summer of 1263, the Norwegians arrived at the mouth of the river Clyde, the Firth of Clyde.

They managed to capture some castles and then entered into negotiations with the Scots, both sides fiercely debating the sovereignty of the islands. The Scots were outnumbered and hoped that by negotiating they could win time to raise more troops.

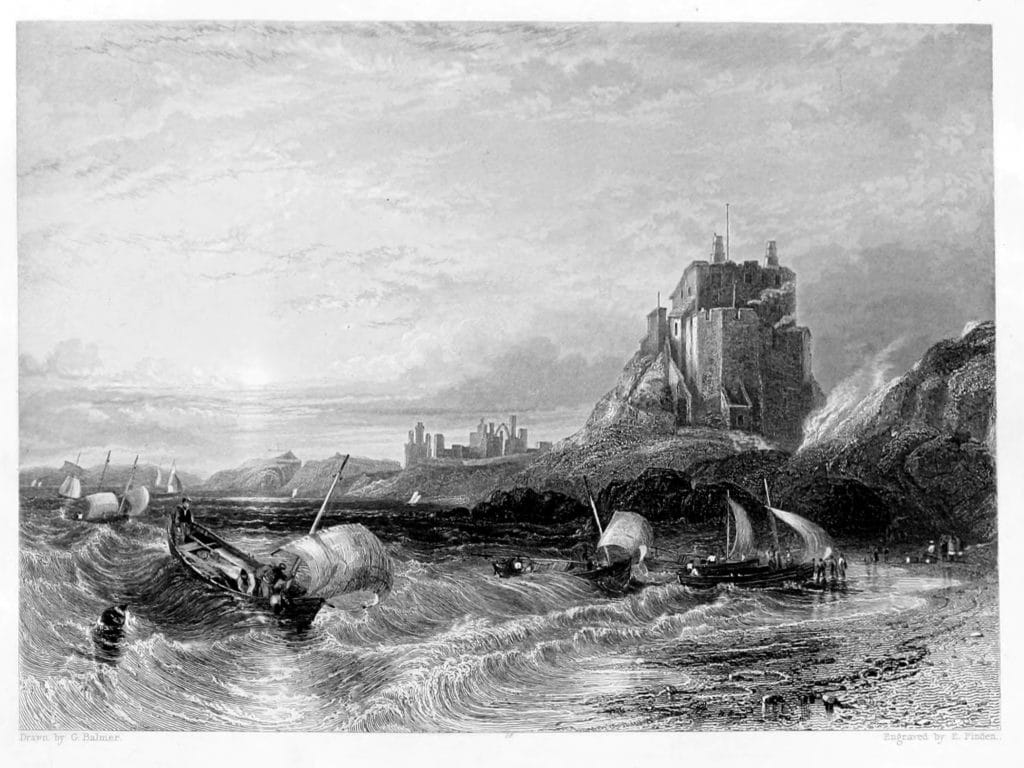

At the end of September 1263, the Norwegian fleet was ravaged by a fierce storm which destroyed some of its ships and ran others aground, forcing the Norwegians to begin salvaging operations.

As this was happening, on 2 October the main Scottish army arrived at Largs, where the Norwegians were anchored, to face off against the Scandinavians. Consisting of heavy knights in the style of the Normans, supported by levied infantry, despite being outnumbered, the Scots gave off a powerful impression.

The Norwegians were split into two groups, a smaller group standing guard on a mound inland from the beach and the main force which was spread out on the beach salvaging the wrecked ships.

According to the Icelandic Sagas which describe the battle, the Norwegians on the mound tried to withdraw to the beach but discipline collapsed as the Scottish vanguard attacked them and they fled in disorder towards the beach.

With a mass of disorganized men fleeing towards them and not being properly organized, the Norwegians decided to retreat to their ships and flee. There was fierce fighting on the beach as the Scots attacked, forcing some of the Norsemen to use the beached ships as forts from which to push back the Scots. After some time, the Scots withdrew from the beach to consolidate, and the Norse took the opportunity to sail away, having suffered heavy losses due to their disorder.

King Haakon had lost a great deal of men, supplies and ships in the storm and the battle and decided to retreat to Orkney to spend the winter there recovering. Haakon’s campaign never recovered as he soon fell ill and died while in Orkney.

Negotiations continued but Alexander spent the next few months winning over the local Norse lords and punishing those who supported the Norwegians.

In 1266 the Norwegians finally signed a peace pact, the Treaty of Perth, handing over rule of the Western Isles and the Isle of Mann to the Scots.

This effectively ended Norwegian power in the region; the Scandinavians would never again seriously threaten the British Isles.

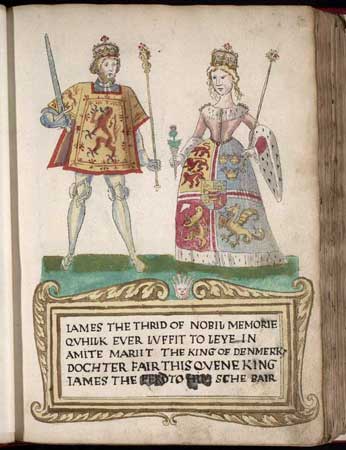

The last few islands of Orkney and Shetland would be absorbed by Scotland in 1471 as payment for the dowry of a Norwegian princess.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend