DETROIT: This isn’t the first-time electric vehicles have been popular.

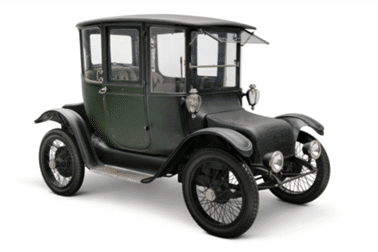

In 1914 Clara Ford, Henry Ford’s wife, opted to drive a Model 47 Brougham from Detroit Electric instead of her husband’s Model T that had been on the market since 1908. The reason was simple. She didn’t have to turn a crank to start the car and there were no troublesome gears to fiddle with. Driving was easy—get in and go.

Clara’s electric car could speed along at 20 mph and go 80 miles without a charge. She drove her Detroit Electric for a dozen years.

But in the 1910s, electric vehicles (EVs) were already losing to the internal combustion engine (ICE). Roads had improved. Consumers wanted to travel longer distances. Electrics had a short range and no charging infrastructure. Gasoline had become abundant and cheap. The electric starter eliminated the crank. Mufflers diminished engine noise.

EVs are winning

Fast forward 100 years and EVs are winning. Pressured to reduce carbon emissions to prove their green credentials, governments are declaring war on ICE vehicles. In Norway by 2025 all new cars, urban buses, and delivery vans must be carbon zero. In China, the world’s largest car market, the province of Hainan, is the first region to ban the sale of cars powered with fossil fuels by 2030. The European Union will ban the sale of ICE vehicles in 2035. California, the world’s fourth largest economy, is phasing in restrictions leading to only zero emission vehicles being sold by 2035.

In the US, South African-born Elon Musk and Tesla are in the vanguard of the EV revolution. Tesla’s first family vehicle, the model S, arrived only ten years ago. Today three million Tesla cars have been sold. EV enthusiast Sandy Munro, the respected independent Detroit-based engineer, says “Musk rattled the industry and turned everything upside down.”

Ford chief executive Jim Farley says the EV transition is happening much faster than expected. He believes 2023 will see the beginning of mass EV adoption. To position Ford for the new era, Farley is creating separate ICE and EV divisions and spending billions on new facilities in the Midwest state of Kentucky. Ford wants to sell 600 000 EVs by 2024 and two million by 2027.

Likewise, General Motors, Ford’s in-state rival, says it hopes to sell one million EVs by 2025. This year GM has doubled its share of the US EV market to 8%, even though that accounts for a mere 5% of GM production. Tesla remains dominant with a 63% market share.

China will dominate

Data suggests China will dominate the EV market. It is already number one in EV production. Five million EVs are rolling on Chinese roads and the market is exploding because of Beijing’s requirement that 40% of vehicles sold in 2030 must be non-polluting. Chinese companies sold three million EVs in 2021, a huge increase over the previous year. Four of the top five manufacturers are Chinese (BYD, SAIC, Chery, GAC) with Tesla having only a 6% market share. Much of the production from Tesla’s Shanghai Gigafactory is exported.

To be clear, it’s not just government mandates accounting for the surge in EV sales and popularity. Consumers increasingly want to do the right thing, making a tangible statement that they are helping to combat climate change. EV buyers like the rapid acceleration and ease of operation. Maintenance is minimal with no oil changes or transmission repairs. EVs have earned high safety ratings. With electricity being cheaper than gasoline in the US, there are cost savings in excess of $1 000 annually from not having to fill the tank. Charging stations are proliferating. There’s a $7,500 tax credit on some models. And some EVs are reasonably priced. The compact Chevrolet Bolt sells for $26 000, with a range of 259 miles. Early market leader Nissan Leaf costs $28 000 and has a 212-mile range.

Nonetheless sceptics abound. Suburban Washington service station owner James Spicer, who drives a Toyota Tundra, says EV pickups and vans are only for short-haul runs by plumbers and electricians. “Try pulling a boat 50-miles with an EV,” he says, “and watch the driving range quickly collapse.” Others point to the contradiction of fossil-fuel generating plants making electricity to charge EV batteries. There’s also the risk of fire from exploding batteries and a shortage of lithium and rare earth minerals used in batteries.

Engineer and industry consultant Sandy Munro dismisses these complaints. He argues there are plenty of chargers and more all the time. He says batteries will be recycled and mineral shortages overcome. Munro believes we’re in the midst of a great transition and “it’s game over for legacy manufacturers slow to wake up.”

As to the question posed at the beginning—Are EVs the Future of Driving?, the answer at this stage is a resounding yes.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend