This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

11th November 1918 – Józef Piłsudski assumes supreme military power in Poland – symbolic first day of Polish independence

The First World War saw one of the most chaotic shuffles of European political geography in the history of the continent.

As the war intensified, each side attempted to drag more and more factions and countries into the conflict on their side to secure victory.

One of these groups was the Polish nationalists.

As the war dragged on, the Central Powers, Germany and Austria, promised in 1916 that from the territory of the Russian Empire, an area known as Congress Poland, they would create a Polish state.

The Germans hoped that this would be a puppet state indirectly under control of the German government, and would motivate Poles within Germany, Austria and the Russian Empire to support the Central Powers.

Many Poles were nationalists who longed for the restoration of a Polish state after partitions had destroyed an independent Poland at the end of the 18th century at the hands of Prussia, Russia and Austria.

Despite the destruction of the Polish state Poles continued to revolt against Russian rule in particular, and attempted to reestablish Poland (which you can read about in this edition of This Week in History). Despite the failure of these revolts, Polish nationalism was not diminished in the slightest.

On 5 November 1916, the German’s issued the so-called ‘5th of November Act’, promising the creation of a new Kingdom of Poland. The Act was extremely vague in its terms, and the Germans largely planned to ignore it if they won the war, but it would prove influential in recreating Poland.

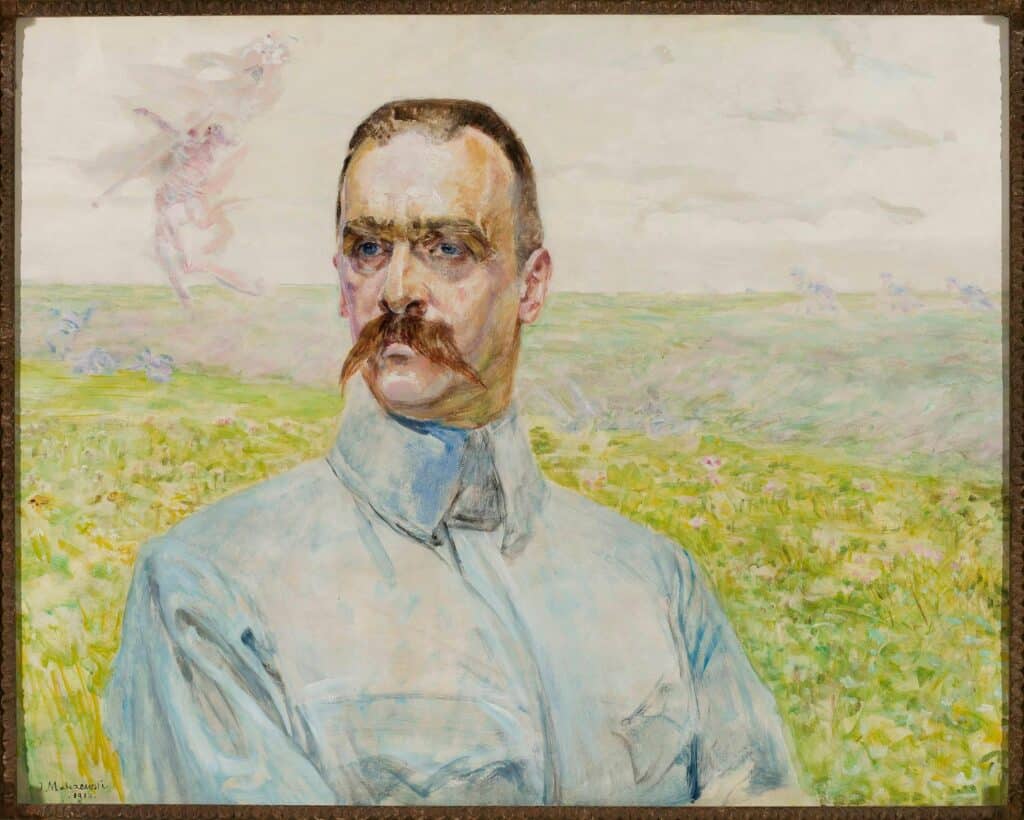

A month later, in December 1916, a Polish government was created in accordance with the Act, and hich was called the Provisional Council of State. This was chaired by a man named Józef Piłsudski, a Polish noble, born in modern-day Lithuania.

As a Polish activist, Piłsudski had previously been exiled to Siberia by the Russian Empire for his nationalist activities. He had also been a member of the Polish Socialist Party, and had maintained armed resistance against the Russian Empire in the early years of the 20th century.

Prior to the outbreak of the First World War, Piłsudski had begun organising the beginnings of a Polish army, which by 1912 had reached 12 000 members, training under cover as members of ‘rifle clubs’.

At the start of the war, Piłsudski hoped that the Central Powers would defeat Russia, and would then in turn be defeated by the French and British, and that this would be the only path to secure permanent Polish independence.

Piłsudski established the ‘Polish Legions’ as part of the Austrian army, but often defied orders so as to operate as independently as possible in pursuit of his own nationalist objectives.

In 1917, Russia was knocked out of the war, and – as planned – Piłsudski switched allegiance to the Entente powers of Britain and France. When in July 1917 Germany and Austria ordered Polish troops to swear allegiance to the German Emperor, most of them, at Piłsudski’s urging, refused. They were subsequently either arrested or forcibly drafted into the Austrian army to be sent to fight in Italy.

Piłsudski was imprisoned by the Germans.

However, his hardline stance had made him a hero among the Polish nationalists, who now saw him as the foremost Polish leader.

On 8 November 1918, three days before Germany lost the war, Piłsudski was released from prison and travelled back to Poland.

With Germany about to lose the war, the Polish government, now called the Regency Council, broke free of German control.

On 11 November, the Regency Council declared Piłsudski head of the Polish armed forces and declared the independence of Poland. Piłsudski managed to negotiate with the German garrisons to peacefully leave the capital, Warsaw; most of these troops abandoned their weapons to the Poles.

A few days later Piłsudski was placed in control of the Polish government, and he quickly worked to bring all of the Polish political authorities peacefully under the banner of the new government.

He also managed to bring on board the Polish Socialists and enacted many of their demands, which involved better working conditions and women’s suffrage. However, when greeted as ‘comrade’ by some of his former socialist allies, Piłsudski said: ‘Comrades, I took the red tram of socialism to the stop called Independence, and that’s where I got off. You may keep on to the final stop if you wish, but from now on let’s address each other as “Mister”.’

Poland had been devastated by the war, and Piłsudski had to quickly reestablish both the economy and the army to avoid the country being swept up in the chaos enveloping Europe, especially the former Russian Empire, which by this point was embroiled in a brutal civil war and faced multiple revolts in the Baltic countries, the Caucasus and Ukraine.

Within two years Poland would face a Soviet invasion as part of an effort to reincorporate Poland into the Soviet Union, and would defeat the Soviets at the Battle of Warsaw, covered in this edition of This Week in History.

Poland was here to stay.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend