The post-Covid lockdown shocks, inflationary pressures, recession, and rising discontent across the world are increasingly threatening governments.

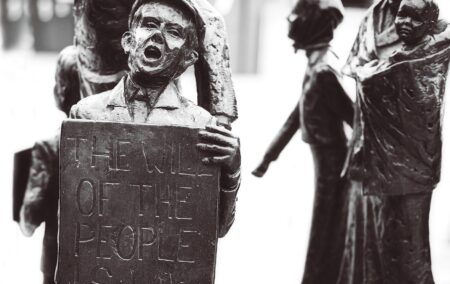

Nationalism and populism have run their course for the moment, and what seems to be strengthening is support for democratic values and accountability.

A few years back there was a widespread, but certainly not pervasive, international disillusionment with democracy. Its slow processes did not allow for rapid action to protect jobs, grow the economy, and defend national interests. And in authoritarian countries many were happy with the stability and growth, and with that could accept a certain degree of repression.

Donald Trump in the US was able to tap into a strong vein of support from the disaffected who wanted a leader who would offer protectionism, a strong defence, and could rally against the woke and liberal in the US culture wars.

Trump has now peaked. He failed to bring about a landslide victory in the midterm elections. And some of those he endorsed tried to distance themselves from him as they attempted to widen their voter appeal. His announcement of his candidacy for President in 2024 was not followed by a wave of endorsements or enthusiasm in his party. Many Republicans might view Trump as a liability, as he mobilises a strong turnout by Democrats at the polls. A Trump exit could mean there might be greater moderation and a less toxic atmosphere in US politics.

In Brazil, President Jair Bolsonaro, the Trump of the South, lost to Lula da Silva, despite Lula having spent time in jail for corruption. The tide may now have turned against right-wing populism, at least for the moment.

Some politicians in developing countries were looking longingly at the Beijing Consensus, China’s authoritarian economic and political growth model, rather than the Washington Consensus. But the recent mass demonstrations in China and the country’s deep-seated problems as well as its lack of democratic flexibility have shown the Beijing Consensus model to be beset with problems. Authoritarian governments are more vulnerable to violent overthrow than democratic ones. And besides, in a democracy a party overthrown at the polls has a chance at power again in the next election.

Strong desire

Demonstrations in both China and Iran have convincingly shown that there is a strong desire for democratic accountability that neither of these governments can ignore. Russian President Vladimir Putin may yet face internal political outrage over the invasion of Ukraine.

In China, the recent demonstrations are a protest against the lockdowns as part of the zero-Covid policy, but they are also a cry for greater freedom.

For some time across China, there have been a growing number of protests against the illegal grabbing of land and harsh police action, but this time the demonstrators are taking aim at a national issue, the zero-Covid policy. Reports by the BBC quote the protesters as calling for the resignation of Xi Jinping, who just weeks ago received another term in office as head of the Communist Party.

The demonstrators are clearly prepared to put themselves at great risk. In China, on the whole, demonstrators are within bounds if they protest against local issues. As soon as they step onto national issues they begin to challenge Communist Party authority.

A heavy police crackdown is now ending days of protests, but their scale has to indicate considerable dissatisfaction and that the Chinese authorities have a big problem on their hands. Scrapping the zero-Covid policy might be seen as backing down, and therefore is a course the Chinese Communist Party would be reluctant to take. It would also allow more people on the street who might wish to demonstrate.

Mounting pressures

This occurs at a time when there are mounting pressures on Chinese economic growth. The country’s population growth rate is below what it was before the one-child policy was scrapped in 2015. China’s export-oriented growth is meeting the constraints of protectionism. In the West there is now disillusionment with the idea that faster growth and greater contact with open societies would yield to democratic gains in China.

So the rulers could have a problem, particularly as the country’s great economic success and relative social stability lie behind the authority of the Chinese Communist Party.

In Iran there have been weeks of demonstrations across the country despite multiple deaths of protesters. The protests were sparked by the death in detention of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old woman who had been jailed by morality police for not wearing a headscarf or hijab. The nationwide protests are probably the most serious challenge to the ruling clerics since the Iranian Revolution in 1979. Defiance against the theocracy appears to be growing, but it might be a long leap for these to translate into regime change.

These protests and those in China show that 2023 might provide a rough ride for other authoritarian regimes. As with the Arab Spring in 2011, violent demonstrations can quickly spread from country to country.

And Russia might also face domestic challenges. It is very difficult for the Russian government to play its defeats in Ukraine as anything but defeats. Russia is showing its increasing frustration in Ukraine. It has conscripted many more and sent them to the battlefront with little effect so far. It is now targeting power stations to ensure the Ukrainians suffer through winter. The war is far from over, but NATO support for a very determined ally fighting with great agility could still impose a greater cost on Russia. While Western sanctions might not be having the desired impact so far, they could in time. And having to spend increasing amounts on a wasted military campaign is diverting resources from ordinary Russians and will have to drive up economic suffering and discontent.

Problem with revolution

Never before has the Russian invasion been so risky for Putin’s political future. While there might yet be mass protests, if change comes it will be by one faction pushing out another and not through democratic election. That’s the problem with revolution. People on the streets demonstrating for accountability don’t often understand that.

In South Africa, judging from the low turnout at the polls – only around 30 percent in last year’s local government election – there is a deep disillusionment with democracy. People may see democracy as desirable but useless in bringing what they need. The opposition parties will have to counter this disillusionment to get people to the polls and restore faith in democracy. After so many years of ANC rule, that is a key but very difficult task.

[Image: TitusStaunton from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend