This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

2nd December 1989 – The Peace Agreement of Hat Yai is signed and ratified by the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) and the governments of Malaysia and Thailand, ending the over two-decade-long communist insurgency in Malaysia.

The first Europeans to arrive in Malaysia were the Portuguese who conquered the city of Malacca City in 1511. For the next few decades, the region which would become modern Malaysia, was heavily contested between the Portuguese and some of the local Malay Islamic Sultanates, who had dominated the region before the arrival of the Portuguese. This fighting left all sides weak, and in 1641 the Dutch East India Company arrived and captured Malacca. From this point on the Dutch would become one of the major powers in the region, eventually establishing a vast colonial empire across the Southeast Asian Archipelago, which would eventually become the modern nation of Indonesia.

The Dutch would rule much of Malaysia, until the Napoleonic wars of the early 19th century, which saw the arrival of the British in the region as a major power. Much as happened in South Africa, the British captured Malaysia whilst the Netherlands was under French occupation, but after initially handing the colony back to the Dutch after Napoleon’s defeat, the British would assume control over Malaysia in 1825 as part of a treaty with the Dutch to divide up the region.

Malaysia did not however exist at the time as a unified region, and rather was a broad political term for a variety of colonies under British rule, which included the Straits Settlements, various Islamic sultanates under British Control, as well as the British colonies in northern Borneo, east of the Malay peninsula.

In 1925, the Chinese Communist Party established a number of branches across South East Asia, Malaysia was in the sphere of the South Seas Communist Party and was mostly supported by a small group of Chinese labourers and intellectuals based out of Singapore. In 1930, these overseas Chinese parties were dissolved and reformed into a number more local communist parties, one of which was the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) which would become the predominant communist party in Malaysia. The party remained fairly small and weak during the 1930s however, continuing to be based mostly amongst the Chinese minority and even unknowingly elected a British agent as its Secretary General in 1939.

During the 2nd World War Malaysia came under the occupation of the Japanese, which greatly weakened British control over the region as the perception of British invincibility was shattered. As the Japanese invasion began, the British authorities were desperate for more troops turned to the MCP for help, who until now they had been working to supress and freed all the communist prisoners, they held in exchange for the MCP joining the anti-Japanese defence. Once the British in Malaysia surrendered, the MCP continued to fight against the Japanese occupation as partisans.

Once the Japanese had been expelled, it took a few weeks for the British troops to return, a power vacuum which was briefly filled by the various partisan groups who had fought the Japanese including the MCP. This greatly strengthened the MCP’s military power as for a short time it was able to collect funds and openly recruit.

Their hold over the colonies weakened, the British set about reforming the Malaysian colonies, hoping to centralize them, and in 1946 established the Malayan Union, which unified the various protectorates and colonies of the Malay peninsula into one colony. The new Union allowed anyone resident in the former colonies to become citizens of the new union and stripped the political powers of the various sultans who had previously had local control of much of the region.

There was major opposition to this union from mainly the Malay majority, many of whom wanted to see the Sultans have their political power restored, and by others who resented the large numbers of Indian and Chinese Malays who would be granted citizenship in the new Union. After two years of protest the union was reformed into the Federation of Malaya which restored many of the Sultans’ political powers and tightened citizenship laws. This federation consisted of the sultanates of Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Malacca, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Penang, Perak, Perlis, Selangor, and Terengganu but did not include the city of Singapore, or the British colonies in Northern Borneo which had also been considered part of British Malaya.

As these changes were taking place, the MCP which had initially in the aftermath of the 2nd World War sought to move towards independence peacefully, turned quickly in favour of a military solution.

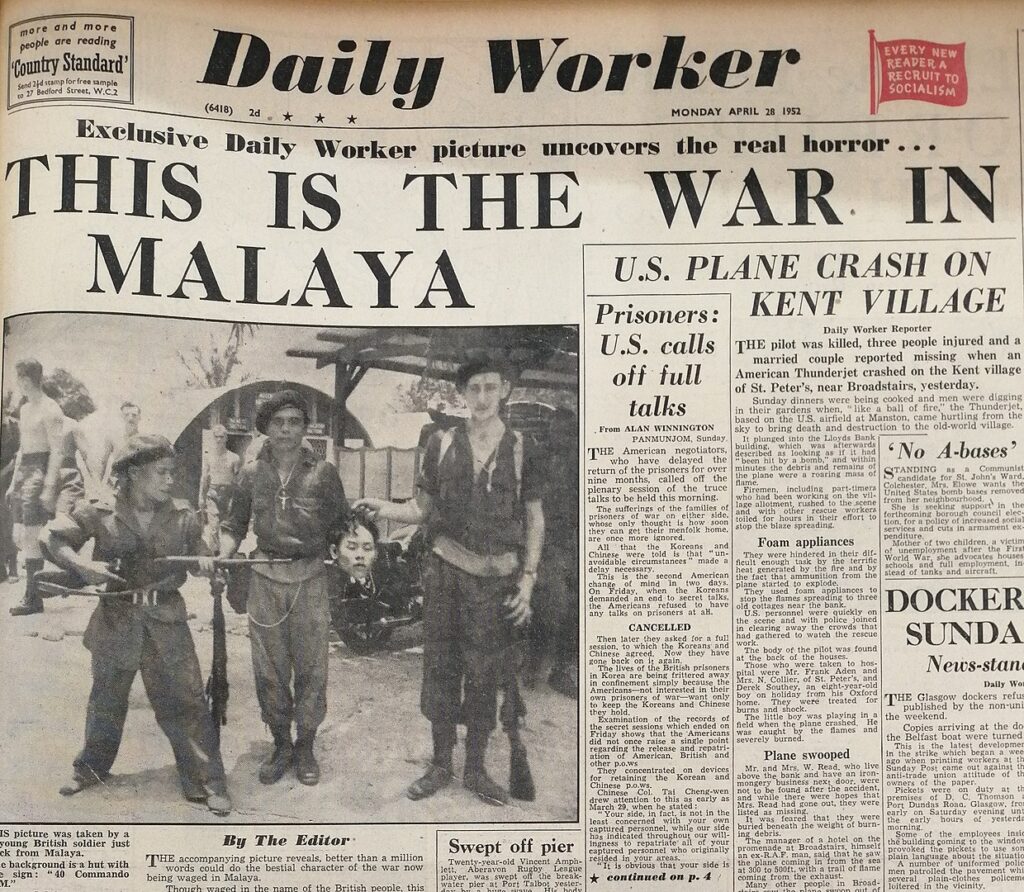

After a number of communist activists were killed by British authorities, the MCP and its large number of partisan fighters from the 2nd World War, led a number of attacks on plantations across the Malay peninsula. In response in 1948 the British government declared the Malayan Emergency. This began a brutal conflict which has become popularly known as “Britain’s Vietnam war”.

The communist forces were however quite small and the British deployed troops from across their empire to help deal with the insurgency, drawing troops from Kenya, Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Fiji, Nepal, Australia, New Zealand as well as support from the army of Thailand.

The British carried out a policy of scorched earth, attempting to destroy the food and supply sources of the communists, who mainly drew support from rural Chinese-Malays. This included the use of internment camps into which suspected communist sympathisers were forcibly moved to prevent them supplying the communists. The communists fought by carrying out raids on colonial forces, assassinating and torturing anyone sympathetic to the British and by ambushing British patrols.

The relative isolation of the communists from foreign assistance, the British numerical and material superiority as well as the experienced British commanders who had learned Jungle warfare fighting the Japanese in WW2 saw the Commonwealth forces slowly crush the communists.

In 1955, the communists seeing defeat as inevitable, sought to negotiate with the Malay government and the British authorities. These talks would fail, but by 1957 the communist forces had almost entirely disintegrated.

As the war raged on, the British had been preparing for decolonization, and on the 31st of August 1957, the Federation of Malaya became independent of the British Empire.

In 1958, the last communist forces were forced north to the border with Thailand and in 1960 the now independent Malay government declared the communist emergency over.

A few years later, in 1963 the Federation of Malaya joined together with the newly independent colonies of Singapore, North Borneo, and Sarawak to form the modern nation of Malaysia.

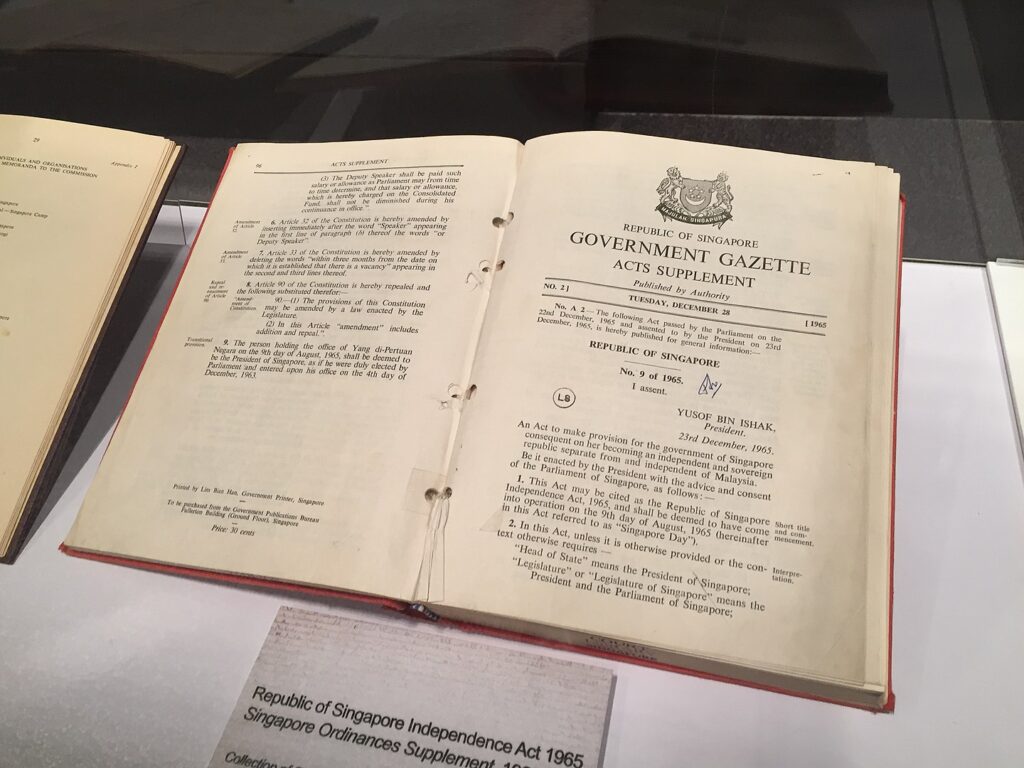

Tensions quickly flared between wealthy Singapore and the rest of Malaysia, as the Singaporeans and Malaysians had major political disagreements. There was also simmering racial tensions between the Malay majority and the Chinese minority who dominated in Singapore. Malaysia demanded that pro-Malaysian affirmative action be implemented in Singapore and after a series of race riots, Malaysia expelled Singapore from Malaysia, forcing it to become independent.

Lurking in the shadows, the Malaysian communist party despite its defeats in the first war, had not been entirely destroyed, and during the 1960s as Malaysia went through its painful birth as a nation, the communists reorganized, retrained and began planning for a 2nd uprising. Now with support from the communists in China, Vietnam and the Soviet Union, the MCP also made efforts to win over Malaysia’s Muslim majority by claiming there was no incompatibility between Islam and Communism.

On the 17th of June 1968, the MCP began a 2nd war against the Malaysian government.

This 2nd uprising was initially much more successful than the 1st, as the communists had much more foreign support and had extensively prepared. As before, they focused on recruiting from the Chinese minority, using the pro-Malay affirmative action policies to stoke resentment amongst disaffected Chinese youths.

Whilst having more foreign support than before the major communist nations still did not commit many resources to the MCP, and the Malaysian government received help from, Thailand, Singapore, the British, the Americans, the Australians, the New Zealanders, and the Indonesians, as well as some limited support from South Vietnam.

The insurgency remained quite small, and in 1970 was torn apart by a major internal conflict, which greatly weakened it as it splintered into multiple factions. Nevertheless, it continued to simmer away in the jungle with the Malaysian government never quite managing to put it down.

In 1974, the pressure began to increase on the communists to surrender as China decided to realign with the west against the Soviets, and opened diplomatic relations with the Malaysian government, who asked them to pressure the MCP into surrendering.

Change was slow to come, and it was only in 1988 that the MCP’s leaders finally decided to open negotiations with the Malaysian government.

The resulting Hat Yai agreement was a total defeat for the communists forcing them to disband their armed units, cease militant activity, destroy their weapons and pledge loyalty to His Majesty the Yang di Pertuan Agong of Malaysia.

Signed on the 2nd December 1989, the agreement brought an end to a communist insurgency which had raged on and off for 40 years.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend