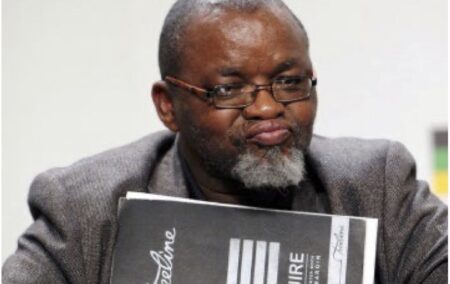

Gwede Mantashe, Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy, has become a familiar sight in politics. He is overly portly, wears a distinctive “bokbaard”, is supercilious in manner, and has a lazy verbal delivery (if you can decipher his mumbling).

He can be funny, though, to us, he’s mostly condescending and dismissive.

His now infamous interview with Kyle Cowan of News24, which Ivo Vegter dealt with in the Daily Friend, shows Mantashe at his most repellant: supercilious, patronising, racist, and wrong. That is less what he said than how he said it: he was combative and irritable.

Clearly, questions about his and his department’s performance are not something he feels he should have to put up with.

Mantashe said:

- The responsibility of the minister of energy is not to connect megawatts to the grid. ‘My responsibility is to approve’;

- Eskom is pitting society against the state;

- Eskom is letting generation capacity lie idle;

- He had approved grid access of about 6 700 megawatts – 3 200MW of which could not be approved immediately due to grid access problems;

- By not resolving load-shedding, Eskom was ‘pitting society against the ruling party’ (see 1. above). ‘Liberal analysts and journalists’ write ‘rubbish’ in the media; and

- Many supporters of some opposition parties wished (load-shedding) would persist ‘because it will give them power’.

Mantashe has an enormous amount of power in his portfolio, so why is he fumbling and irascible? Is it because he doesn’t know what or how to do his job? No doubt, he believes he deserves power because he is the chairman and a powerbroker in the ANC. But, like so many of his colleagues, he just can’t do the job, and as the problems multiply, he seems to become more incapacitated.

An article by Mark Barnes in Business Day recently analysed what has beset governance more fundamentally under Jacob Zuma and Cyril Ramaphosa, and is destroying the fabric of our society.

‘Incompetence, particularly when found in leaders, is an infectious disease of the worst kind. Where it manifests the consequences are dire, if not terminal, for the host enterprise,’ says Barnes.

Barnes notes that once it presents at the top of an organisation, its spread is practically guaranteed. He argues that the more the incompetent try to do, the more obvious their incompetence becomes.

It follows, I suggest, that consequently they end up doing nothing, as a means of disguising their inadequacy.

In the day-to-day management of an entity, competence is tested almost continuously. Says Barnes: ‘All the more so when circumstances are challenging, where difficult decisions have to be made that require knowledge and experience. People who don’t know what they’re doing avoid making any decisions at all.’

Barnes, unfortunately, is right when he says that the most common way incompetent leaders deal with their incompetence ‘is to ensure that those around them are also infected’. This is axiomatic: competence below will highlight competence above. However, even if a manager isn’t competent in every area under his authority, a competent manager knows where the gaps are and hires the right people to fill those gaps.

The filtering down of incompetence ‘becomes the culture of the organisation and merit gives way to failure as a refuge, the safety of failing in numbers. The organisation eventually fails. There are no exceptions’.

Perhaps Mantashe is facing what Barnes predicts: ‘Nobody will respect you, and eventually they’ll stop listening when you’re still holding forth. Some always know what has to be done, and they’ll know you don’t.

‘You’ll become grumpy, develop an inferiority complex and your internal anxiety will eat you up… You’ll become a thug, a bully, a façade of bravado concealing a melted middle of despair.’

Sounds like the Mantashe we know. Mantashe became the minister of mineral resources, and the portfolio was merged with energy in 2019. In four years under his management the department has not even produced a gigawatt of power.

Barnes opines that ‘leaders don’t need to spend most of their time seeking consensus or even asking their followers where they should go — the notion is absurd. Leaders know where the mountain is, often because they’ve been there before’.

This is probably the key element to good leadership; real leaders make tough, often urgent decisions, and they take responsibility. Of course the ‘leader’ who comes to mind inevitably is President Cyril Ramaphosa.

The absence of these traits is most prominent in the President. Ramaphosa is a consensus-seeker. Seeking opinions, as opposed to consensus, goes without saying, but at the end of the day, to qualify as a leader you need to have the courage to make a decision, make it timeously, and above all be prepared to take responsibility for the consequences.

Ramaphosa’s leadership style reflects none of this. Sadly, the missed opportunities are legion. Ramaphosa came into power on the back of the ruinous nine years of Jacob Zuma’s rule. He was measured, reassuring, seemingly experienced and warm. It didn’t take long for him to become considerably more popular than his party.

Theoretically this should have been the perfect opportunity to take the ANC in any direction he chose. He didn’t. He consulted everyone – the tripartite alliance, labour, business, the community. The only person he didn’t factor into the equation was the voter. But a leader shouldn’t have to consult the voter; the voter elected the party to meet the voters’ mandate. Ramaphosa had to just get on with the job and ensure his ministers did too.

Ramaphosa was revealed to be not a businessman, nor a decision-maker, nor courageous. When interviewed after his first year in power by eNCA, he was asked before the formal interview commenced how he had found his first year in office. He said that it had been very hard; much harder than he expected.

His immediate reaction to the parliamentary report into ‘Phala Phala’ was that he would resign. He probably would have been greatly relieved to have stepped down. However Mantashe persuaded him that the ANC’s performance in the 2024 election depended on his personal popularity. This was even though Ramaphosa’s popularity had plummeted after Phala Phala. And the one thing we do know about Ramaphosa is that the ANC’s survival is more important to him than that of the country.

If you find incompetence already entrenched when you arrive, there is no choice but to dismiss the incompetent unless they can be moved to an area more conducive to their skills. This must be done as soon as possible. Removing the incompetent often has two results: first, it takes pressure off everyone else and, second, the person removed may be relieved to be out of a situation he or she can’t cope with.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.