This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

3rd March 1857 – Second Opium War: France and the United Kingdom declare war on China

At the dawn of the 19th century, China, ruled at the time by the Manchu Qing dynasty, was a power in decline. Though still one of the world’s largest economies and a great power in Asia, China was increasingly outclassed by the industrialising powers of Europe.

Despite the growing importance of European trade, the Chinese state tightly controlled trade with Europe and from 1757 to 1842 it forced all trade with European merchants to pass through the port of Canton (modern day Guangzhou).

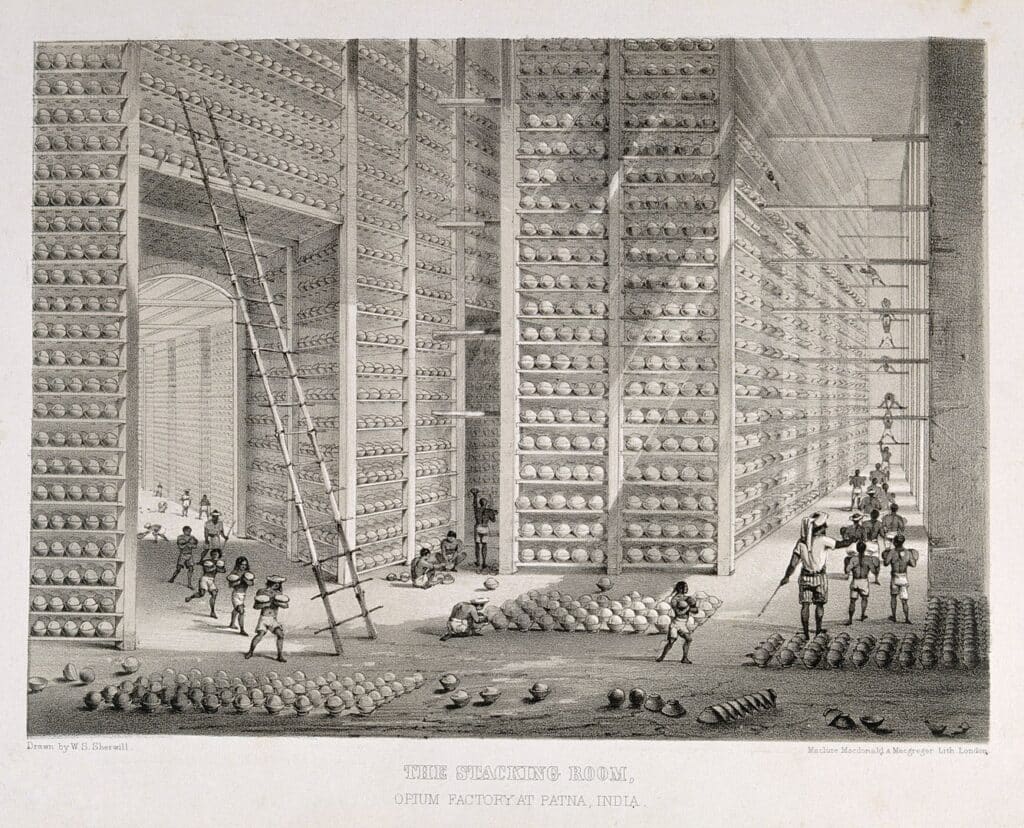

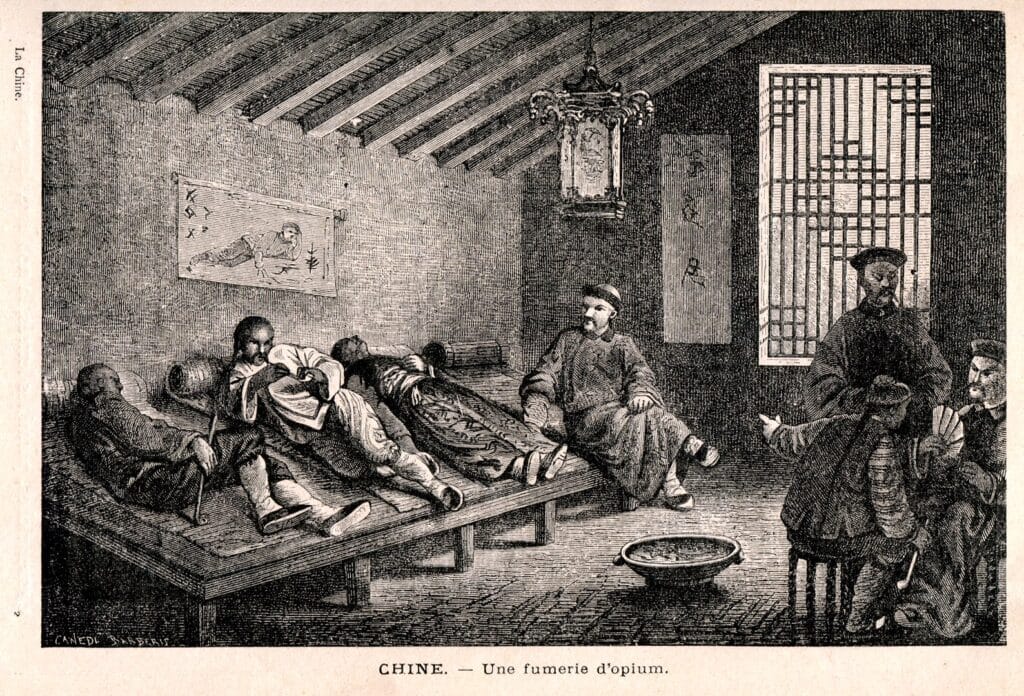

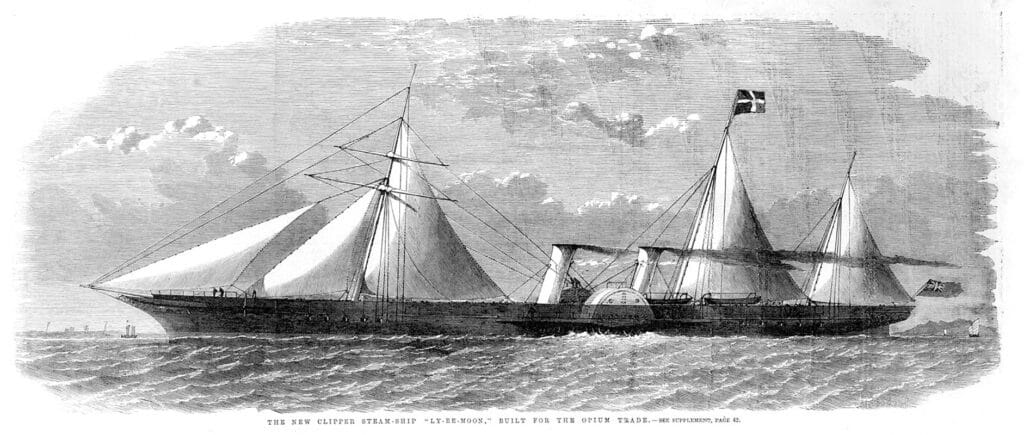

In the 18th century, the British had begun to allow the growing of opium in their colony in Bengal, selling the drug to smugglers who imported huge amounts into China, so building a vast market of opium addicts, and undermining the control of the Chinese state over foreign trade.

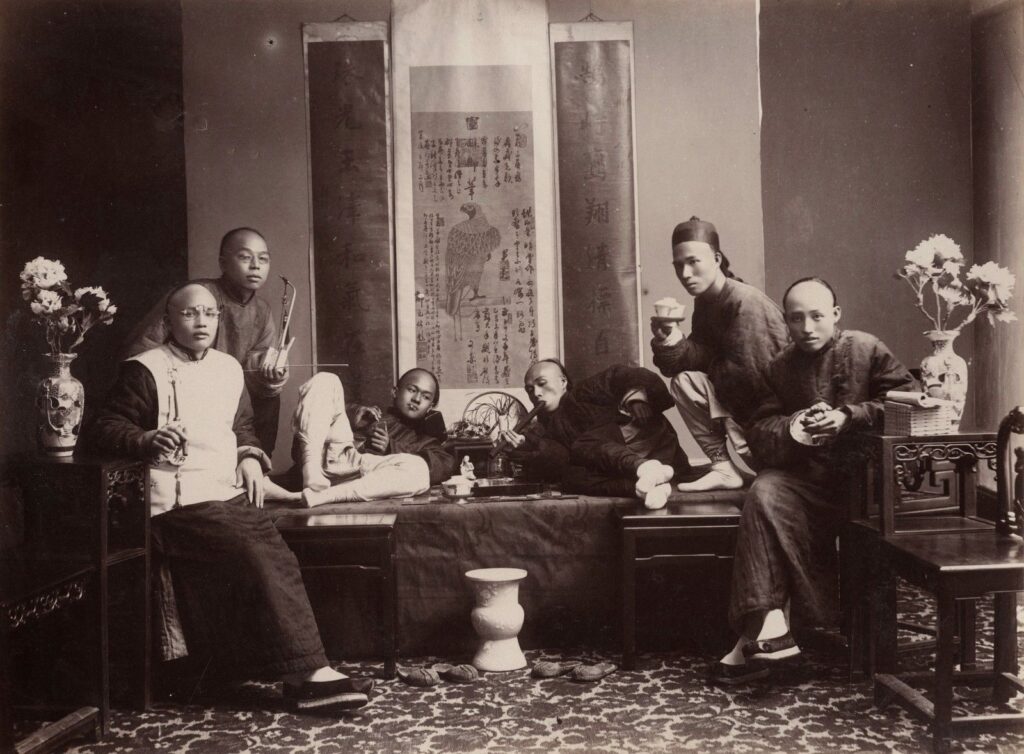

The growing list of problem created by the opium trade for the Qing state – chiefly, addiction and weakening control over trade networks – compelled the Qing emperor to take action.

Some proposed that the Chinese state legalise opium and tax it to force the trade back into the realms of legal control by the state, but the emperor believed this would only worsen the addiction problem.

In 1839 the emperor appointed a new governor to Canton, charged with completely crushing the opium trade. The new governor even wrote a letter to the recently crowned Queen Victoria appealing for her aid in stopping the trade. The letter was never shown to the young queen.

Things came to a head in mid-1839 when British sailors were sheltered from a murder charge by the British authorities after the killing of a Chinese villager; in September, war broke out.

Over the next three years, the British humiliated the mighty Chinese state, defeating Chinese troops in unevenly matched battles and smashing the Chinese fleet in a number of engagements. This was possible due to the excellent quality of the British navy as well as the use of new technologies, such as steam-powered ships.

The Treaty of Nanking signed in 1842 in the aftermath of the Chinese defeat led to the number of ports the British were allowed to trade in being expanded to include Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai. It also established limits on some tariffs, and compelled the Chinese to pay reparations to the British and to cede the island of Hong Kong to the British crown. Opium, however, was not legalised.

In the aftermath, America and the French soon began to demand their own treaty ports with which to trade, and signed similar agreements with the Qing government.

Relations between the Chinese government and the British remained poor in the aftermath of the First Opium War. In 1847, when British subjects were killed by the Chinese, the British launched a minor punitive expedition and seized forts in the Pearl River Delta.

Seeing the new deals the Chinese had signed with France and America, the British sought to expand their concessions. After the arrest of a British merchant crew by Chinese authorities in 1856, the British would declare war again.

This time they demanded the opium trade be legalised, the exemption of British imports from internal tariffs, an end to piracy and a further opening of China.

The French would soon intervene on the side of the British after the execution of a French Christian missionary by Chinese authorities in a province that was closed to foreigners.

During the course of the war, Russia and America would both offer aid to the British, but only America would actually send any troops.

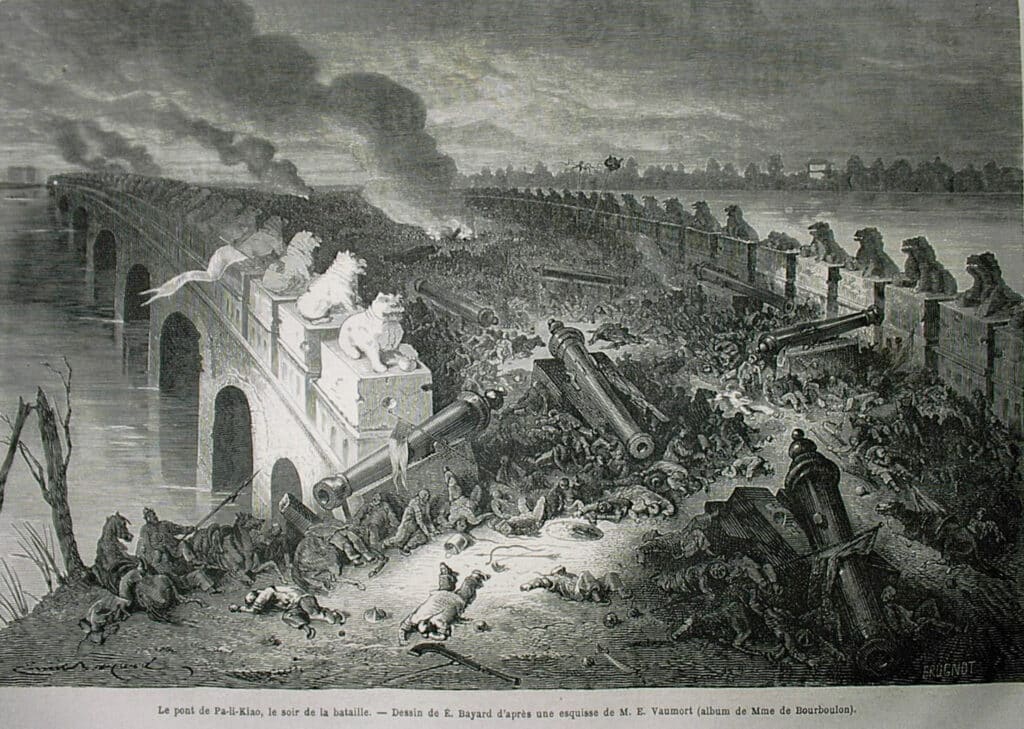

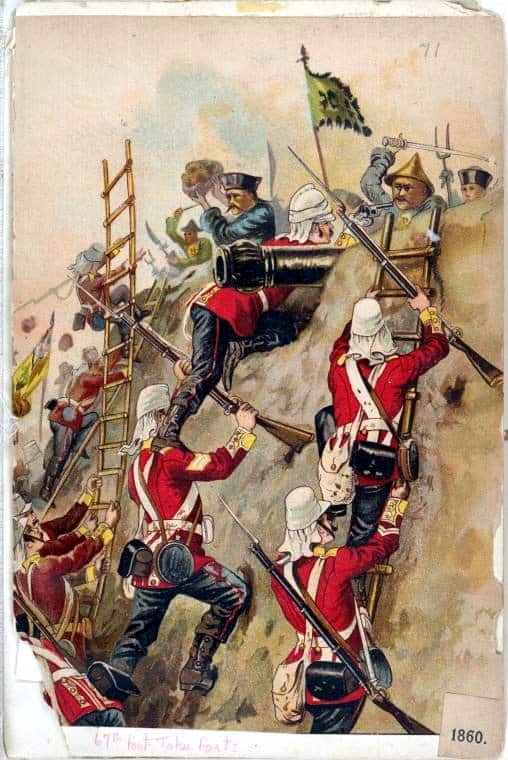

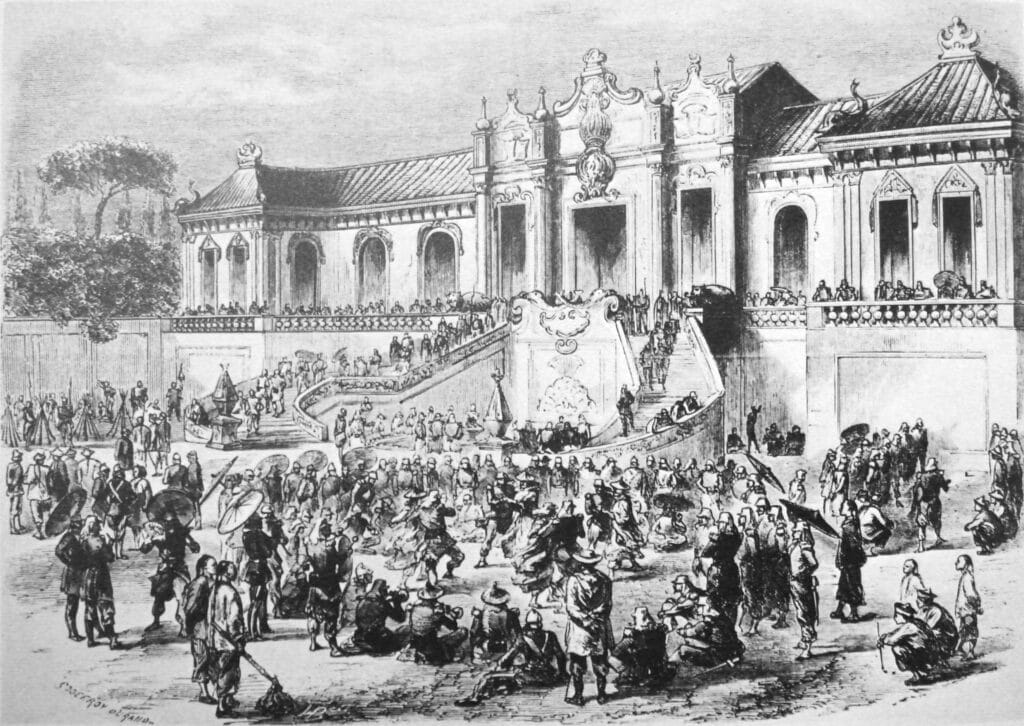

In 1860 the Chinese state would be defeated again, with Western troops entering Beijing and forcing the emperor to flee.

The new treaty opened up another 11 ports to Western trade, allowed Britain, France, Russia and America to establish embassies in Beijing, permitted foreign vessels to sail into the Yangtze River, allowed foreigners to travel across China, instituted further reparations, legalized the opium trade and enjoined China to allow freedom of religion.

The First and Second Opium Wars were part of China’s ‘century of humiliation’ during which Chinese nationalist historians believe China was subjected to repeated humiliations by powerful foreign empires. This view of history still strongly influences Chinese foreign policy to this day.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend