I

As the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution approaches, I’ll offer these revisionist thoughts about the country’s beginnings.

First, it was essentially a civil war. At the time of the 1776 Declaration of Independence the 13 American colonies had a population of 2.4 million of which 61% were ethnically British. Most proudly declared themselves to be English. When fighting began a year earlier one-third of the population, 800 000 people, were loyalists wanting to remain British subjects. Boston lawyer, John Adams, said a third of the people wanted independence, another third did not, and the final third waited to see who would win.

Second, the revolution was led by wealthy elites, slave-owning southern planters, and wealthy merchants in the north. American colonial society—like that of England—was an aristocracy based on land and money. Several of the wealthy planters and merchants among the 53 delegates to the 1st and 2d Continental Congresses were highly educated. John Adams, a Massachusetts delegate to the congress, declared the gathering in Philadelphia, “a collection of the greatest men on the continent.” Importantly, ordinary people who favoured independence did not resent the prevailing social order.

Third, the revolution would have failed without French participation. So much is owed to the Marquis de Lafayette, whose landowning family was among the richest in France. A fixture at the court in Versailles, married and a father at 17, Lafayette was smitten with the lofty ideals of the Declaration of Independence. He was also eager to fight the British at whose hands his father died commanding French troops in the Seven Years War. In June 1777, having arranged with American agent in Paris, Silas Deane, to be a senior officer in the Continental Army, Lafayette purchased a ship and sailed to America. Altogether the French sent 12 000 soldiers and even more sailors to America.

Fourth, land became currency as there was no American money. There were no banks in the colonies, says historian Willard Randall. Some colonies issued their own currency and prices in British pounds fluctuated greatly within the colonies. Colonial governments were chronically in debt and soldiers were paid sporadically, if at all. After the war the British ceded the Northwest Territory to the Americans and several states paid officers and even privates with bounty lands north of the Ohio River. Only in 1792 did the new United States create a national currency.

II

Why did ordinary people support a revolution led by aristocrats? Because no matter the social order, they believed with the British gone they would enjoy greater freedoms and more opportunity. Historian Arthur Schlesinger addressed this issue in 1962:

“The colonists unhesitatingly took for granted the concept of a graded society,” he wrote. Schlesinger continued, “indeed, (the colonists) possessed a self-interested reason for retaining (a graded society). In this outpost of civilization it was man alone, not his ancestors, who counted. Even the humblest folk could hope to better their condition.”

In Europe, including Britain, most land was controlled by the monarch or the church and unavailable to free holders.

Thomas Jefferson, himself an aristocrat with huge land holdings, spoke of a natural aristocracy, a political elite based on merit not birth, what he called “an aristocracy of minds.”

As to the French, the Marquis de Lafayette was a pivotal figure. He was a major-general in the Continental Army and principal aide to General Washington. Returning for a time to Paris in 1779, the well-connected Lafayette partnered with Benjamin Franklin, America’s chief emissary, to secure vital supplies of French money, ships and men.

In 1781 a combined force of Americans and French under Count Rochambeau marched from New York to tidewater Virginia. With a French fleet preventing British ships from entering Chesapeake Bay, Washington and Rochambeau forced Lord Cornwallis’s army to surrender at Yorktown.

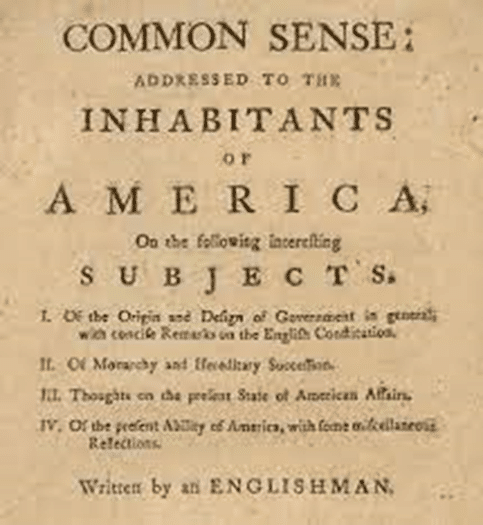

Yes, the revolution was instigated by elites but its triumph is inexorably linked to the inspiring words of Thomas Paine, a tradesman and self-taught intellectual who arrived in America in 1775. In January 1776, months before the Declaration of Independence, Paine published a 47-page pamphlet called Common Sense. Using simple, succinct language, Paine blamed the ills of the colonies on King George III. Only with its own laws and independence from Britain, he argued, could America be free.

“In America the law is king. For as in absolute governments the king is law, so in free countries the law ought to be king; and there ought to be no other…..Ye that oppose independence now, ye know not what ye do; ye are opening a door to eternal tyranny, by keeping vacant the seat of government,” he wrote.

The pamphlet was a publishing phenomenon, read by rich and poor in every colony. Paine was inspired by the bravery of the Massachusetts Minute Men who defied England and battled British regulars at Lexington and Concord in April 1775 in what writer Ralph Waldo Emerson would call “the shots heard round the world.”

Paine biographer WE Woodward wrote that “the publication of Common Sense was like the breaking of a dam which releases all the pent-up water that stood behind it.”

General Washington ordered officers to read the full text of Common Sense to all soldiers. After the war John Adams observed, “history is to ascribe the revolution to Thomas Paine.” The itinerant Englishman, trained as a corset maker, is credited with being the first person to use the term, “The United States of America.”

III

Abraham Lincoln proclaimed in 1865, “our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” These lofty words inspired millions—slaves and indigenous people in the New World as well as European masses yearning to be free.

American patriots prevailed over the world’s most powerful nation. No longer would American colonials be dismissed as second class by their compatriots in Britain. No longer could a venerated Englishman like lexicographer Samuel Johnson call Americans “a race of convicts who ought to be grateful for anything we allow them short of hanging.” Historian J.H. Plumb writes that prior to the Revolution people in Britain thought of America “as a dumping ground for thieves, bankrupts, and prostitutes, for which they received tobacco in return.”

The American Revolution remains one of the grandest events in world history. America for the first time enshrined the promise of freedom, self-government, and the end of the divine right of kings. The Revolution created an American identity.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend