This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

2nd May 1670 – King Charles II of England grants a permanent charter to the Hudson’s Bay Company to open up the fur trade in North America

The first sale of Hudson’s Bay fur at Garraway’s Coffee House in London, 1671

The European fur trade traces its roots to the establishment of greater trading links between Western and Eastern Europe after the 500s. This is when the Slavic and Baltics tribes and kingdoms began to sell increasing amounts of furs from Europe’s colder regions to the more urbanised peoples in Germany, Italy and the Mediterranean.

These furs were mostly the pelts of martens, beavers, wolves, foxes, squirrels and hares. As the population of Eastern Europe grew and began to build larger towns in the 9th and 10th centuries, Russian merchants and explorers began to push east into Siberia to harvest new sources of fur for the growing demand in the west.

For centuries, the east was the only source of fur for Europeans, but starting in the 1500s a massive new source was opened with Europe’s discovery of North America.

Depiction of an indigenous woman wearing a Hudson’s Bay point blanket, circa 1850

Within decades of the discovery of the Americas, hundreds of European fishing and trading ships were traversing the east coasts of modern-day Canada and the United States, engaging in trade with and raiding the local peoples, usually in the pursuit of furs, particularly beaver pelts. Most of the early contact between the Native Americans of the north and Europeans centered on the fur trade, which became hugely important to the economy of many tribes, as the Europeans exchanged iron goods and blankets for furs.

In time, the French emerged as the dominant players in the fur trade, with a French captain being granted a royal monopoly over North American fur trading by the French crown in 1599. The Dutch attempted to break the French monopoly, starting in 1613, but were unable to successfully challenge the dominance of the French.

In 1658 two French fur traders, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseillier, learned from the Cree tribe that there were excellent regions for collecting furs around the poorly explored Hudson Bay.

Arrival of Radisson in an Indian camp in 1660

They would go on an expedition to the area north of the Great Lakes in 1659 and would find great success. However, as they had been denied permission by the French government they were arrested and fined upon their return to the French city of Montreal.

Angry at the French government, the two men sought funding for another expedition from foreigners, in this case the English. They would manage to get financing for a sea voyage to Hudson Bay in 1663 with the backing of English merchants from Boston, but this expedition failed due to thick pack ice.

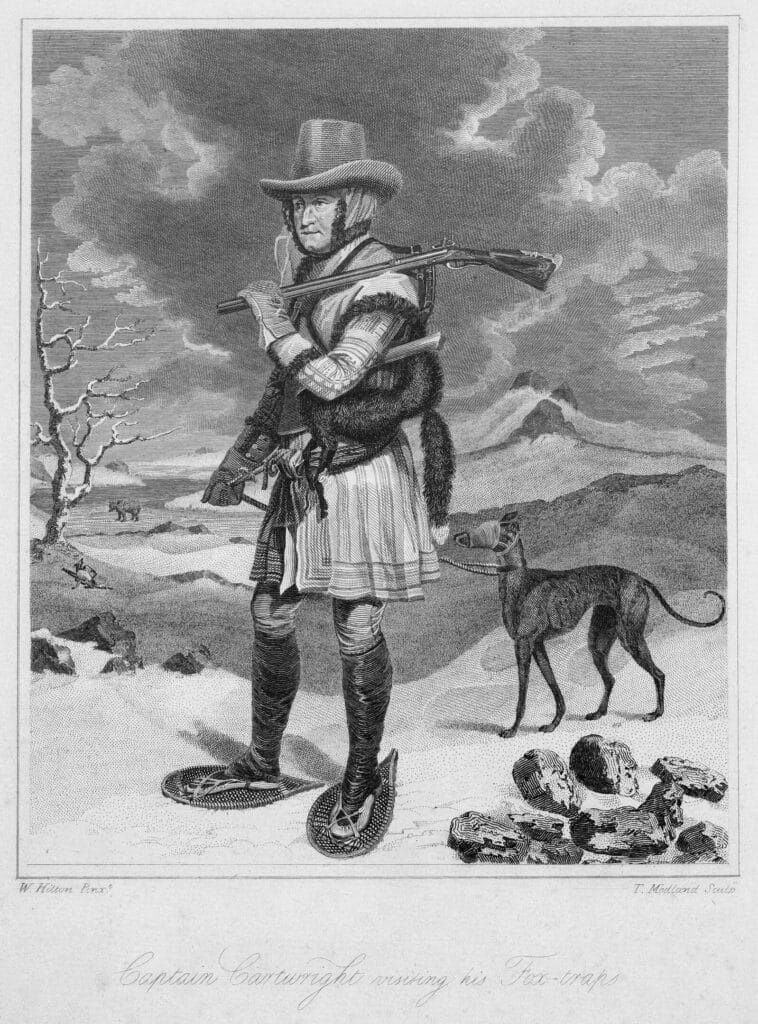

‘Captain Cartwright Visiting his Fox Traps’ in T Medland’s 1792 engraving of W Hilton’s oil painting, circa 1791

The two were taken by an English commissioner, Colonel George Cartwright, to England to raise funds for another attempt. Here, they ended up meeting King Charles II and received sponsorship from the king’s cousin Prince Rupert.

Charles II in Garter robes by John Michael Wright, or his studio, circa 1660–1665

Their next expedition to Hudson Bay set out in 1668.

This expedition was successful, and a small trading fort was established at the mouth of the Rupert River (named for the sponsor of the trip). Their success would give rise to the establishment of the Hudson Bay Company (known then as ‘The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England, trading into Hudson’s Bay’) and the granting of a royal charter allowing this new company a monopoly over fur trading in the region.

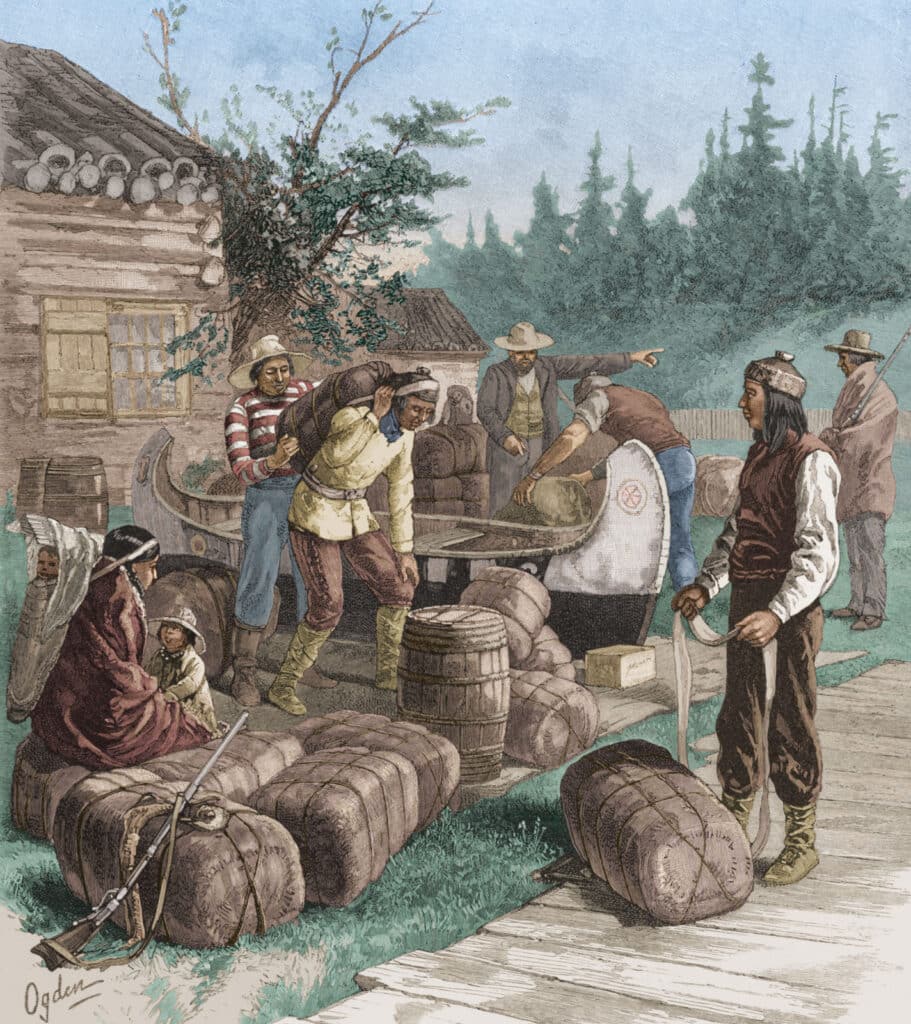

Trading at an HBC trading post

Unlike the French, the English focused their efforts on the coasts, letting the local Native American tribes come to the fort at the end of trapping season, where they would be greeted with a ceremony, following which trading for furs would commence. The French meanwhile were far more integrated with the tribes, establishing numerous small trade stations in native villages across North America, outposts they would use to trade with the tribes. Many of the French traders would integrate into the tribal communities, learning their languages and marrying local women.

By the 1680s, the French sought to displace the English forts, and the two began to regularly attack each other.

After the Nine Years’ War ended in 1697 the French were forced to surrender all of their claims to the area around Hudson Bay to the English and their Hudson’s Bay Company.

The English would not however move to establish more permanent settlements inland until 1774.

In 1763 the French lost the Seven Years’ War to England and gave up all of their Canadian colonies to the English, who now dominated eastern North America without contest.

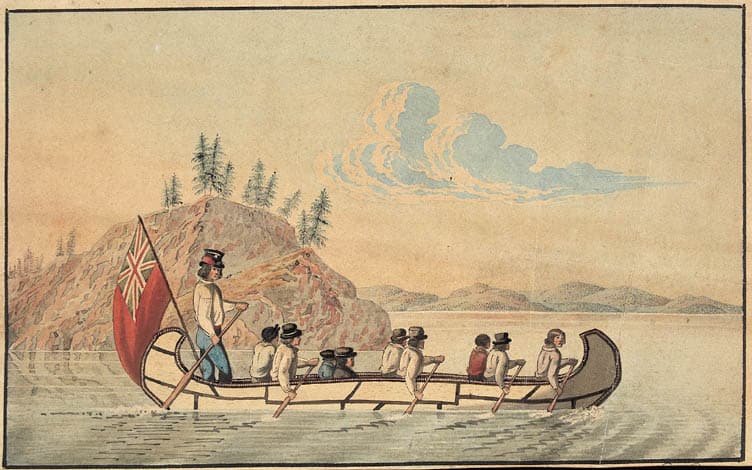

Hudson’s Bay Company officials in an express canoe crossing a lake, 1825

During the late-18th century, the Hudson’s Bay Company had become large and wealthy but was locked in fierce competition with the North West Company, which was based in newly English Montreal.

This competition became so fierce that it led to open conflict between the two companies’ private armies. It wasn’t until after the Battle of Seven Oaks in 1816 that the two companies were forcibly merged by the British government.

Depiction of the Battle of Seven Oaks, a violent confrontation between HBC and the North West Company during the Pemmican War

The Hudson’s Bay Company would continue to play a major role in expanding British influence across Canada and even northern California. Its monopoly was finally ended in the mid-1800s and its influence would shrink.

An HBC store in Vancouver, circa 1890

The company did not die, but adjusted to the modern age by becoming a department store chain. Today the company remains a major retailer in Canada, with 30 000 employees and over 9 billion Canadian dollars in revenue.

The Bay Queen Street in Toronto. It was formerly the flagship store for Simpson’s before HBC converted it to Hudson Bay in 1991 [Canmenwalker, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=114113263]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend