Inflation is on the rampage around the world, causing anxiety, deprivation, and even bank failures. Governments need someone to blame, and who better than greedy capitalists?

Have you ever heard a politician say, ‘I’m sorry. I screwed up. I didn’t listen to good advice, and I broke the economy. People are now suffering because of my poor decisions. I know it doesn’t mean much now, when everyone is saying I told you so, but I humbly apologise. Please don’t vote for me in the next election. Elect someone smarter than me to pull the country out of the mess I caused.’

No? Me neither.

I have heard a ton of politicians blame other people, however. Everything is always someone else’s fault.

The average inflation rate around the world was 7.4% in 2022. That is up from 4.35% in 2021 and 3.18% in 2020.

Of course, there are proximate reasons for this. The pandemic lockdowns, now a fair distance in the rear-view mirror, caused a violent upheaval of supply chains that made everything more expensive.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine more than a year ago caused disruptions in the supply of food and fuel, and even a government economist can tell you that a decrease in supply without a commensurate decrease in demand causes rising prices.

Still, these disruptions do not explain the stubborn persistence of inflation, which despite steeply rising interest rates shows few signs of returning to the fairly modest levels we have become accustomed to since the 1980s.

Blame

My rule of thumb whenever I see a problem with the economy is to assume, unless proven otherwise, that government caused it. This rule rarely fails in our modern world in which governments have grown into mighty Leviathans, and endlessly regulate and tax and subsidise and bail out and otherwise interfere with the self-correcting price mechanism of the market.

It helps that I, like most advocates of free markets, have been warning about the threat of inflation for decades.

But politicians and policy makers can hardly be expected to blame themselves, now, can they? They need to cast about for another culprit. And they’ve found it.

‘How company profits are keeping prices high,’ wrote a compliant Mathis Richtmann for Deutsche Welle on behalf of presidents, central bankers and chief economists. (I’m not claiming a conspiracy here: he probably isn’t aware of it because he lives and works in an echo-chamber populated by politicians, bankers and government-employed economists.)

In their defence, they can indeed point to profit margins that in many industries hit record highs in 2022. World leaders, like Joe Biden, were outraged.

They can even point to a correlation effect that as profit margins came down from those highs, consumer price inflation also eased. But correlation isn’t causation, and as we shall see in this case, both are effects of a different cause.

Wages vs profits

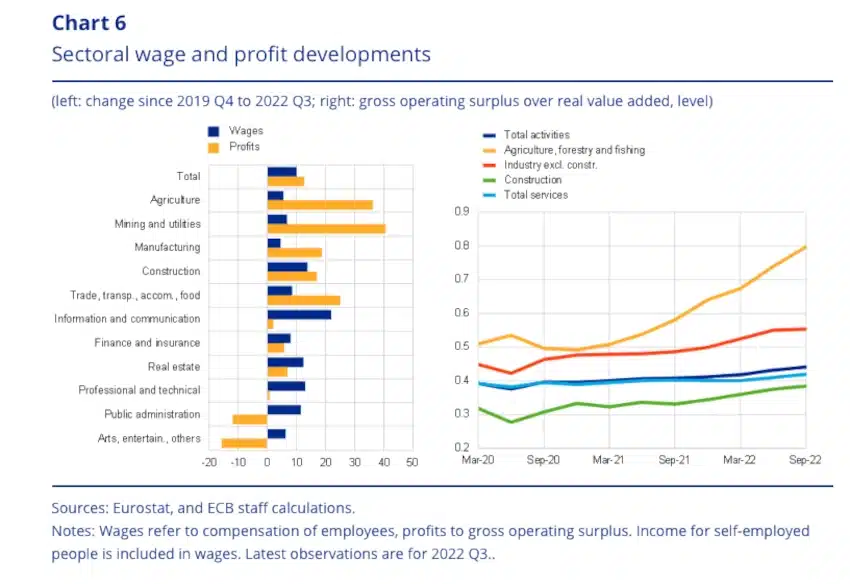

The Richtmann piece points to a chart used by Fabio Panetta, a board member of the European Central Bank, at a recent conference, which shows that in some sectors, like agriculture, mining and utilities, trade, transport, accommodation and food, operating profits have in recent years exceeded wage growth.

It doesn’t point out that the opposite was true in other sectors, like information and communication, finance and insurance, real estate, professional and technical services, public administration, arts, entertainment and others.

It also doesn’t count the untold number of businesses that failed during the pandemic lockdowns, and which are not making any profit at all anymore.

A banker quoted in the piece claims that ‘it was the fog of uncertainty during the pandemic and war that led companies to hike prices’.

Plausible

All this sounds superficially plausible, if you don’t stop to think too much.

Greedy capitalists exploiting crises to fleece the common people? Of course! Isn’t that what the socialist elites that populate the media, academia and government always say will happen if government doesn’t keep a firm rein on business?

Nobody ever points to the amazing products and services and life-saving inventions and modern conveniences that these supposedly greedy capitalists continually produce for us. That doesn’t fit the caricature.

So why is it that corporations weren’t so greedy a few years ago? Have they only recently discovered their ability to raise prices? Why didn’t they exploit the ‘fog of uncertainty’ of the 2008 financial crisis to raise prices and cause inflation, or the ‘fog of uncertainty’ of the 9/11 attacks in 2001?

Where does all the money come from that now appears on the income statements of some – though by no means all – big companies?

Has everybody just been going along with it? Has nobody tried to compete with these super-profit generators? Has nobody tried to economise by reducing their consumption and thereby denying these companies excessive profits? Have these companies just been under-pricing their wares all along, and only now decided to pick the pockets of the poor? Why? Why now?

Prices are not set in a vacuum. Prices are not based on cost, either. Prices are entirely dependent on what customers are prepared to pay. If that price happens to be higher than cost, then a product will be produced. If not, the product won’t be produced – at least, not for long.

A price is always agreed to by both a supplier and a customer; both must believe they benefit from the transaction that establishes the price.

Extra money

So, where does all the extra money come from that has suddenly appeared as headline profits in financial statements?

From the government, of course. Central banks around the world have been printing money hand over fist – known as ‘quantitative easing’ – and pumped it into the economy.

As the monopoly on issuing currency, they have also kept interest rates artificially low – known as ‘easy money’ – in order to ‘stimulate the economy’.

On top of this, governments have provided ‘fiscal stimulus’ from their taxpayer-funded budgets.

In previous crises, most of the quantitative easing and easy money went to banks, to the top of the financial system, where it was issued as cheap loans and went straight into the kinds of assets rich people buy – like stocks and houses – to cause asset inflation.

The dot com bubble that burst in 2000 was fuelled by easy money and a steadily increasing money supply. So was the housing boom that crashed in 2007, exactly as free-market advocate Ron Paul predicted in eerie detail in 2001.

The long stock market boom from 2008 to 2021, which not even the pandemic could slow down, was funded by easy money as well as exceptionally large amounts of new money that was printed in the wake of the global financial crisis.

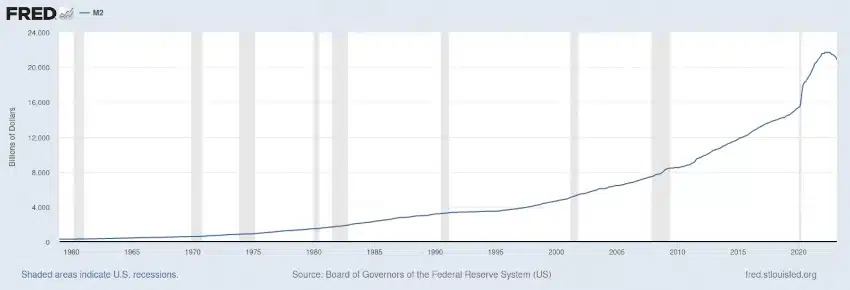

The response to the 2020 pandemic was accelerated money printing. This chart shows money supply over time in the US, but something similar goes for many other major central banks.

Direct to consumers

For the first time, a lot of this money – literally trillions of pounds, euros and dollars – was funnelled directly to consumers, in the form of cash handouts, paycheque protection loans and other subsidies. This way, politicians could appear like they were doing something to ease hardship. Who doesn’t love a politician throwing cash around?

It is no surprise, then, that for the first time, monetary inflation became apparent not only in asset price rises, as before, but also in consumer price inflation.

People had more money to spend because governments gave them that money.

It shouldn’t surprise anyone that all that extra money eventually turned up in profit-and-loss statements, because that is what happens to money that gets spent.

When they say ‘follow the money’, it isn’t about where the money ended up, but where it came from.

It came from governments and central banks, which as a matter of deliberate policy sharply ratcheted up the money supply, which caused both price inflation and the opportunity to make high profits.

Governments love inflation

What government policy makers also won’t tell you is that they actually love inflation. One important effect of monetary inflation is that it devalues the currency. As a consequence, both debt and savings are reduced in value.

Governments have lots and lots of debt which they would love to inflate away. So do rich people. Rich people have large loans and mortgages and credit card debt. That debt also gets inflated away, at the expense of people who save in bank accounts or pension funds. In this way, monetary inflation redistributes money from the poor to the rich.

That is the hidden special interest behind the money supply inflation that causes price inflation: governments and central banks cause it, and governments and wealthy elites benefit from it.

Scapegoats

By deflecting blame onto the companies that simply price their products as they always have, at what the market will bear, the policy makers and politicians are escaping culpability themselves. Listen to all 15 minutes of Ron Paul’s speech from more than 20 years ago.

Read the work of the economists that came before him who were critical of inflationary monetary policy, like Ludwig von Mises, Henry Hazlitt (also here) or Friedrich Hayek. They’re not arcane, or difficult to understand.

They all explained how printing money to artificially keep price inflation positive is a means to deflate government debt and funnel money from the poor to the rich.

Governments were told printing money would cause high inflation. They ignored the warnings.

Now companies are just responding to economic conditions as they found them, and they’re supposedly at fault? They’re just the scapegoats.

Those conditions were created by governments and central banks. They are the culprits, and they alone should be held to account, instead of trying to deflect blame on to the innocent for the entirely foreseeable effects of their own ham-fisted and self-serving economic policy.

[Image: Gerd Altmann from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend