This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

18th May 1804 – Napoleon Bonaparte is proclaimed Emperor of the French by the French Senate

Joséphine kneels before Napoléon during his consecration as Emperor at Notre Dame. Behind him sits pope Pius VII

The French Revolution was in many ways the founding of modern politics. It is from the French Revolution that we get our left wing’ and ‘right wing’ division of politics (based on where each faction sat in the French Estates General).

It also invented the more modern conception of nationalism, and mass conscription of citizens for service in a national army, and it would establish the tragically familiar pattern of radical revolutions mounted against oppression sliding into dictatorships.

In 1789, many French subjects fed up with the misrule of France by the monarchy, the rising cost of food and the lack of taxes paid by the nobility, rose up and initially created a constitutional monarchy. Within three years they would execute their king, transforming themselves into the First French Republic.

Storming of the Bastille

This new republic was incredibly unstable. Outside larger cities some regions of France remained very supportive of the monarchy and launched rebellions against the new government. The Catholic Church was also opposed to the new republic and the monarchies of Europe were horrified at the execution of the king and murder of the nobility which was sweeping France, and so were actively working to crush the new republic.

Despite its supposed founding on a list of human rights and its claim to be based on the will of the people, the republic came quickly to be dominated by a small oligarchy which became ever more dictatorial.

Facing so much opposition, the republic was gripped by growing paranoia and revolutionary fervor, which saw rampant violence and the murder of those considered enemies of the revolution, starting in 1792.

By April of 1793, the rulers of the republic attempted to harness this energy and created the Committee of Public Safety to direct what would become known as the ‘terror’, a directed effort to destroy ‘counter-revolutionary’ elements through public executions and mob violence.

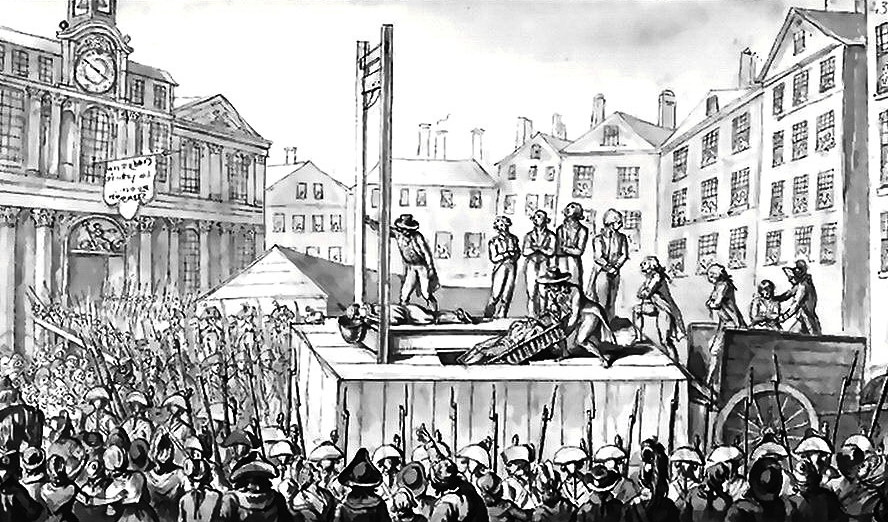

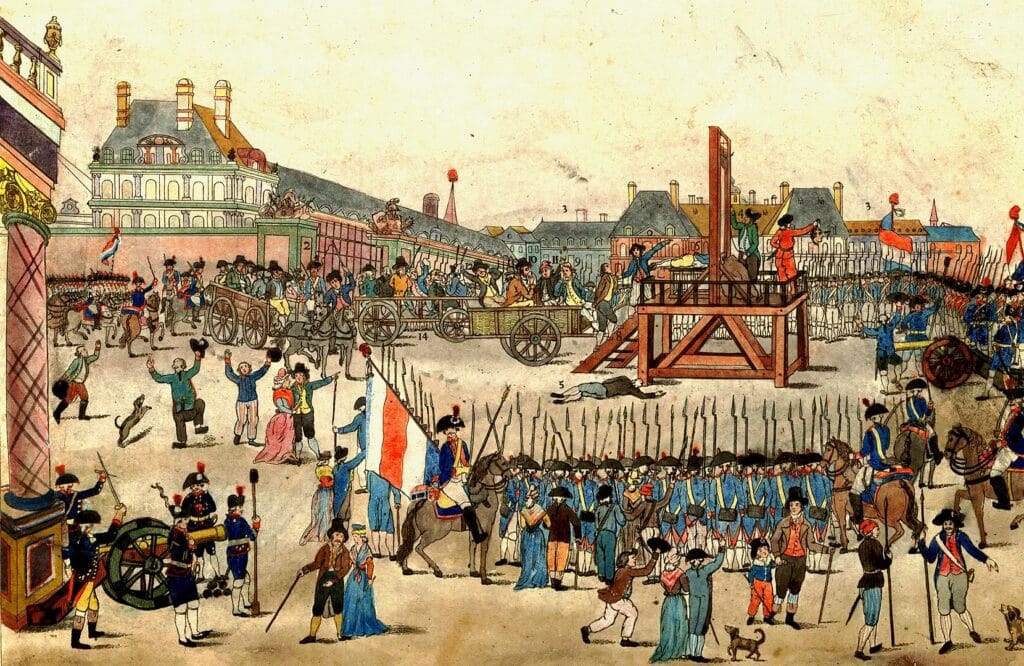

The guillotine in use in 1793

This period of intensified violence soon became a struggle for power between various factions with the dominant faction led by Maximilien Robespierre using it as a way with which to kill political opponents from both the more moderate and more radical factions.

In July of 1794 the paranoia and fear had become so widespread that radical and moderate factions banded together to kill Robespierre, having him and his allies executed on 27 July 1794.

The execution of Robespierre

The new government that emerged attempted to reconcile with the rebels within France, curb the madness of the terror and focus its attention on securing the gains France had recently achieved in its wars with its monarchist neighbours. In 1795 this new government was formalised as the Directory of the French Republic, a committee of five men who would govern France.

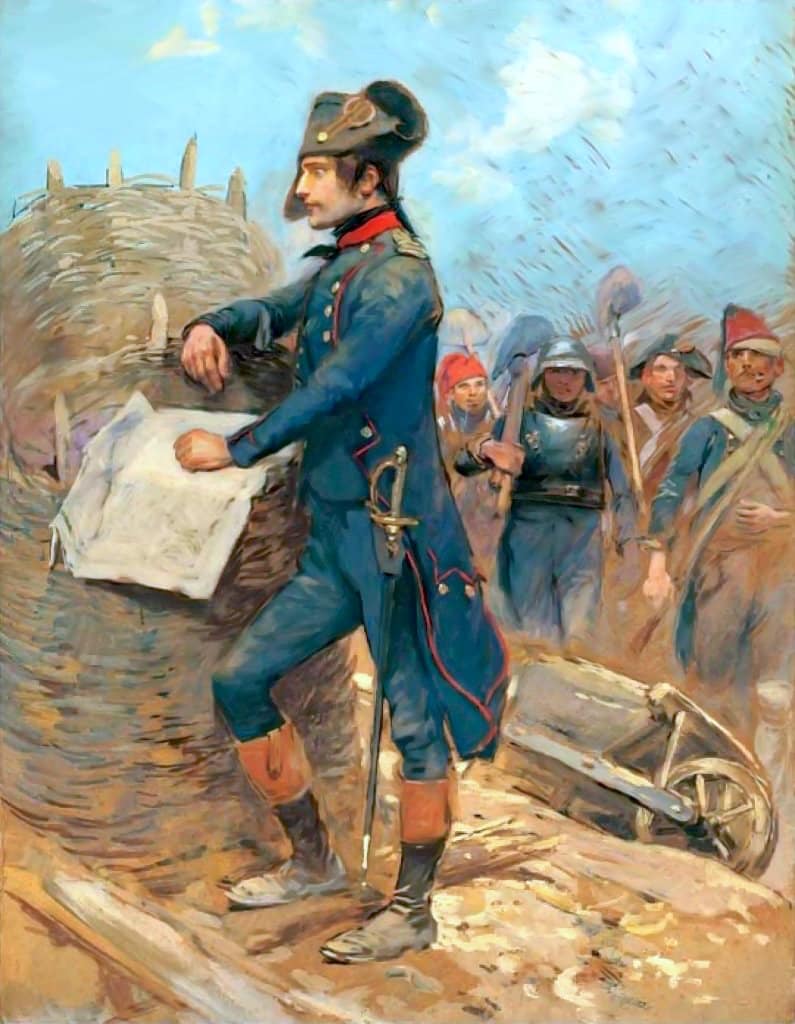

The new Directory faced a number of rebellions, but the most threatening was the October 1795 rebellion just before the formal establishment of the directory. A royalist uprising was defeated with the help of Napoleon Bonaparte, an ambitious army officer who had made a name for himself fighting the British in Toulon but had fallen out of favour due to his refusal to fight the royalists in central France and his perceived closeness to Robespierre.

Bonaparte at the Siege of Toulon, 1793

Napoleon would rise quickly to become the most famous general of the French armies. After his victory over the royalist rebels in 1795, he would be sent to Italy where he would win a stunning series of victories, securing much of Italy for the French and planting the seeds of a cult of personality.

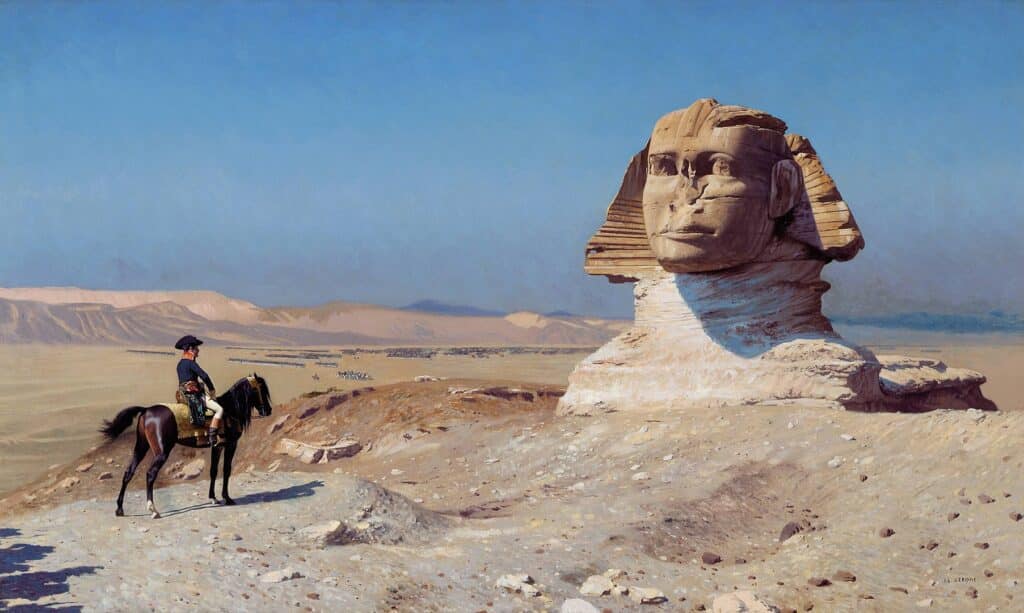

After success in Italy, he would lead a campaign into Egypt and the Middle East in 1798, hoping to carve up part of the Ottoman Empire and link up the French with anti-British Indian forces, with the ultimate goal of destroying the British Empire.

Bonaparte Before the Sphinx (c. 1886) by Jean-Léon Gérôme

During this time, the Directory was plagued with infighting and after some setbacks in 1799 Napoleon, now the most famous and successful of the French generals, returned to France, abandoning his troops in Egypt, and orchestrated a coup which saw the dissolution of the Directory and the creation of the French Consulate, a government with Napoleon as the de-facto military dictator in the guise of First Consul.

After the turmoil, terror and infighting and chaos of the years since the revolution, the French were largely welcoming of a strongman leader who had built a cult of personality around himself.

Over the next few years Napoleon won more victories against numerous European coalitions sent to defeat him and only solidified his power ever more over France. In 1804, in an attempt to defuse royalist plots to remove him, Napoleon planned the creation of a neo-Roman French Empire with himself as the new Emperor.

After holding a referendum in which he was supported by 99% of voters, Napoleon was proclaimed Emperor of the French by the French senate on 18 May 1804 and in December of that year was crowned.

Napoleon I on his Imperial Throne by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1806

Napoleon would rule as the absolute ruler of France until his defeat in 1814. And after a brief return to power in 1815, he would die in exile on the island of St. Helena in 1821.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend