‘We are damned if we don’t find a solution to unemployment – and it’s not really that difficult.’ This was the headline of a short, pithy article in Business Maverick, published on 31 August 2021.

Written by associate editor Sasha Planting, its conclusion was powerful and memorable: ‘Every decision made (by the best possible people in the job) should be made on the basis of whether it will have a positive outcome for job creation — nothing else. Because we are damned if we don’t.’

Employment, or more accurately a shortage of employment, has arguably been South Africa’s most persistent and serious problem; so much so in fact that it has become almost a part of the background noise, something accepted as baked into the country’s economic and social fabric. It’s worth reflecting on what this means.

The Institute’s annual South African Survey, released last week, puts this into perspective. A comprehensive collection of statistics on the state of the country, the Survey has been produced since the 1940s. It is the definitive, dispassionate account of the country, providing not only a snapshot of the year in review, but also detailed time series’ data and international comparisons.

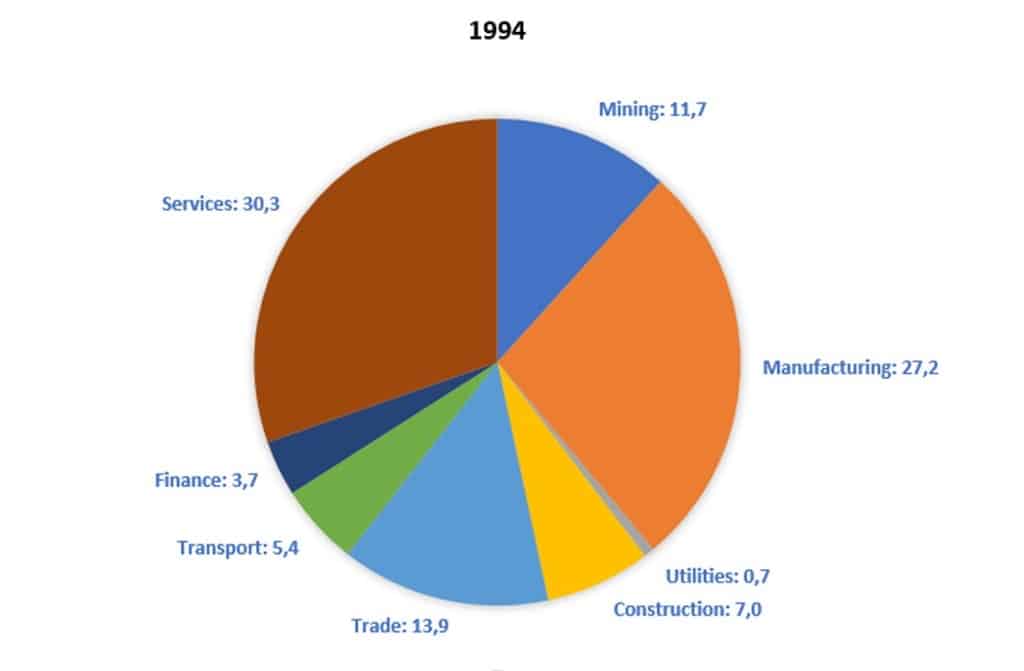

To understand South Africa’s employment crisis, it’s worth first looking at the structure of work and how it has evolved over the past three decades. This is illustrated in the graphs below.

Note that the centre of gravity in the economy has shifted decisively away from the primary and secondary sectors towards services. Mining and manufacturing in 1994 accounted for 38.9% of employment; in 2022, this contribution stood at 16.4%. General services (which includes government) remained broadly constant, from 30.3% to 27.9%. The big growth was in trade and finance: from 13.9% and 3.7% to 21.5% and 23.3% respectively.

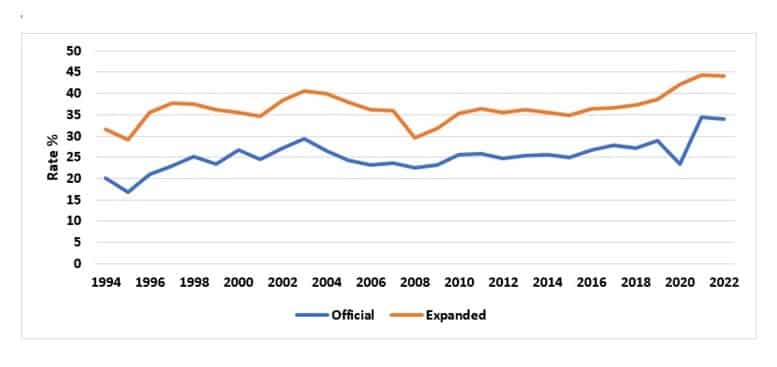

Meanwhile, unemployment has moved upwards; evenly so, but unmistakably.

South Africa officially defines unemployment as lacking work, wanting and being available for work, and actively seeking it. By these measures, the rate has grown from 20.0% in 1994 to 33.0 in 2022. This is serious enough – compare this to economically prostrate Greece at 12.2%, distressed Brazil at 8.9% and even despondent United States at 3.5% – but if the so-called ‘expanded’ definition is considered, the picture is positively catastrophic. The expanded definition dispenses with the requirement that those without work be actively seeking work; it therefore included those who are discouraged from seeking work. By the latter measure, the unemployment rate shot up from 31.5% to 44.1%.

Even this does not sketch the full picture.

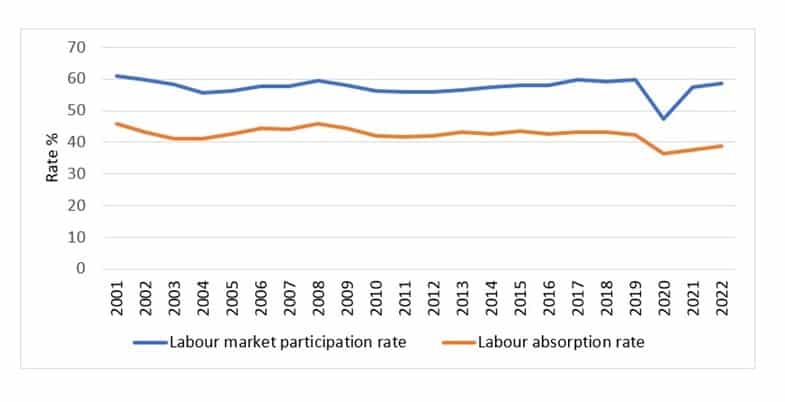

The labour participation rate measures the proportion of the working-age population that is economically active: those who are employed and unemployed but in the labour market. It distinguishes these from the economically inactive, which includes full-time students, homemakers and pensioners.

Fallen slightly

This has fallen slightly, over time – from 60.8% in 2001 to 56.8% in 2022 – although this is not enormously significant. Most South Africans want to enter employment.

More significant is the labour absorption rate. This measures the ability of the economy to take on potential workers. (It is defined as the proportion of the working-age population that is employed, in other words, all those who do any work for pay, profit or family gain.) Just as unemployment has risen, so has the labour absorption fallen. In 2001, the labour absorption rate stood at 45.8%; in 2022, it was at 37.8%.

In sum, the ability of the economy to take on new entrants, not great at the beginning, has fallen to dismal levels.

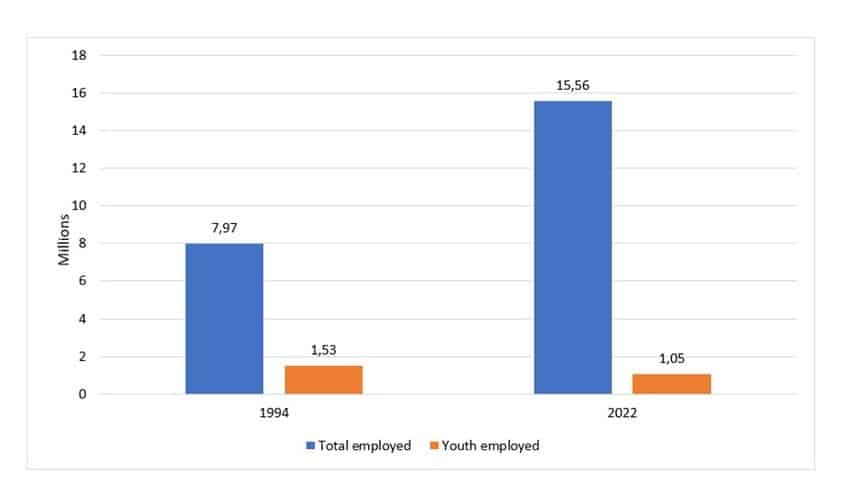

The impact of this is well illustrated by looking at the raw numbers. In 1994, total employment stood at close to 8 million. In 2022, the number of employed had more than doubled, to 15.5 million.

But note too the number of young people employed – those between the ages of 15 and 24 – actually fell, from 1.5 million to a little over 1 million. It’s worth reiterating that: a half a million fewer young people are in employment now than was the case at the time of the transition.

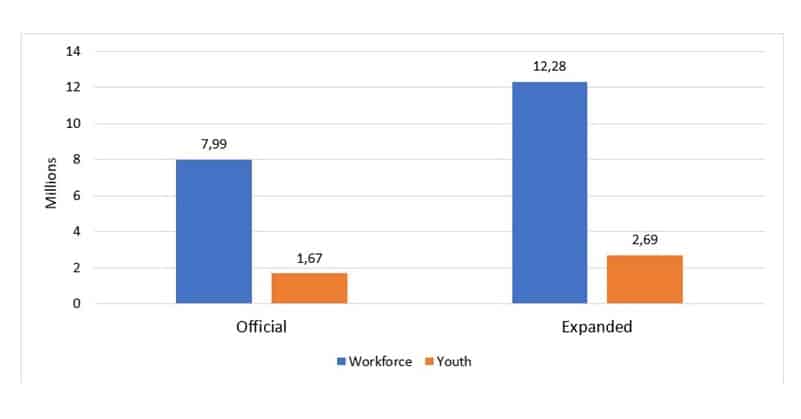

Indeed, a look at the actual numbers of unemployed drives home the severity of the crisis. This is shown in the figure below, which shows the number of unemployed in 2022.

Those officially defined as unemployment amount to just under 8 million; of these, 1.7 million are youth; by the expanded definition, 12.3 million people are unemployed, of whom 2.7 million are counted as youth. (To put that last figure into perspective, for every young person with a job, close to three lack one.)

This, then, is South Africa’s unemployment crisis.

It’s important to view it in context. South Africa’s population stands at 60.6 million. At the time of the transition it was estimated at around 40 million. A burgeoning population demanded a rapidly expanding economy, itself driven by high levels of investments, to furnish those jobs. Yet this has not happened, with the partial exception during the mid-2000s.

Meanwhile, the vicissitudes of the global economy, the fullness of which the country re-entered in the 1990s, meant that what was being done needed to be done that much more efficiently. For parts of the economy, especially manufacturing, this proved fatal. Increased competition combined with the onerous burdens of the labour regime simply proved too much.

With the relative decline of the ‘blue-collar’ economy, opportunities for millions of less educated people were circumscribed.

In addition, a failure of the education and training systems to produce the ‘skills revolution’ that was punted in the 1990s has locked millions of others out of the growth areas. Ironically, a lack of skills overall is one acknowledged constraint for South Africa’s prospects, and this is aggravated further by a migration regime that has never been properly tailored to the needs and capacity of the country it is meant to serve.

Ideologically driven phantasms

To this must be added the failings in power supply, in water, in logistics, in the regulatory regime more broadly (what is gingerly called ‘policy uncertainty’), not to mention ideologically driven phantasms such as expropriation without compensation and race-based ‘empowerment’ policy, and the brakes on job creation become only too apparent.

Above all, this has hit South Africa’s young people hard. Many face a future in which even unglamorous and rudimentary options appear shut. This is not only a tragedy for the wasted potential and frustrated ambitions of millions; it is a very real threat to South Africa’s stability.

As Sasha Planting said, get this right or South Africa is damned. The evidence supports this.

This is an edited version of Corrigan’s remarks at the launch of the Survey last week.

[Image: alejandroavilacortez from Pixabay]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend