That recycled blocks of onshore shale gas prospects are coming up for auction in, oh, a year or two, reflects the chronic inability of South Africa to support oil and gas production.

South Africa has its knickers in a twist over offshore seismic exploration, based on absurd pretexts such as that the souls of the dead live in the sea.

The Karoo shale gas exploration saga stretches into – what is it now – its 14th year? It has been delayed by environmental fearmongering based on claims that are fabricated or grossly exaggerated, as well as litigation on narrow procedural grounds. Both of these were strategies to delay approvals until the companies seeking to explore gave up in exasperation.

Meanwhile, several big oil and gas rigs (and some $300 million in investment) are descending upon Namibian waters, to exploit its side of the Orange Basin, where a number of finds were made in recent years. South Africa’s side of the same basin lies largely undeveloped.

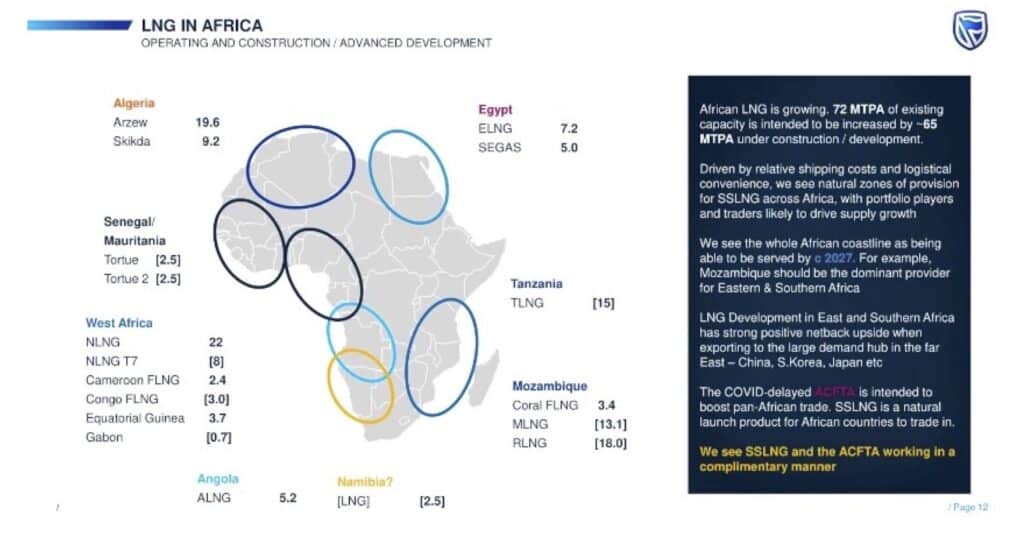

The following slide is from a deck by Standard Bank, which finances several oil and gas projects in Africa. It outlines advanced liquified natural gas (LNG) developments in Africa (the numbers indicate millions of tons per annum):

The government ought to be ashamed that it hasn’t been able to put South Africa on this map, despite years of promises to make oil and gas a key pillar of economic development.

Worked out

Mossgas is worked out, and the PetroSA gas-to-liquids plant in Mossel Bay has not had feedstock since 2020. South Africa’s open-cycle gas turbines all run on diesel instead of natural gas, which is dirtier, less efficient and far more expensive.

What gas the country does have is being imported, predominantly from Mozambique. We could turn dollar outflows into massive dollar inflows by lighting a fire under the responsible ministers and green-lighting exploration and production on an accelerated timeline.

The finds in Namibia are very large, contain both oil and gas, could break even with an oil price between $20 and $30 a barrel (it’s $75 today), and offer an excellent internal rate of return.

Yet the only oil and gas field that is being developed in the Orange Basin, is Ibhubesi, in which the state-owned Central Energy Fund owns a 24% stake. It is expected to come online in 2025, producing mostly natural gas. By the sound of things, most of it will be destined for export via Saldanha Bay.

Two more offshore gas finds, Brulpadda and Luiperd are being developed by TotalEnergies in the Outeniqua Basin about 200km due south of where I live.

They are working on an accelerated schedule by applying for a production right while they’re still exploring and appraising the find. A final investment decision is expected in 2024, and, if positive, the hope is that the fields will enter production in 2027 or 2028.

Declined to zero

And that’s it. There are vast areas of other promising offshore blocks out there, but none are being developed.

The map of exploration and production rights produced by the Petroleum Agency of South Africa has hardly changed since I used it for my book on environmental exaggeration more than a decade ago.

While Africa’s combined gas production has increased by 70% since 2000, that of South Africa has declined to zero.

After 14 or so years of wrangling with environmentalists about the rights to explore for and produce natural gas from the potentially large reserves found deep under the Karoo, the government is largely back at square one, offering exploration blocks for auction that were abandoned by Shell, which got bored of waiting and figured it might actually make some money somewhere else (like in Namibia).

There is also still significant uncertainty about potential future gas offtake facilities in South Africa, which makes the investment landscape more speculative than it needs to be.

Ridiculous

It is ridiculous to argue, as environmental elitists do, that a country with a poverty rate north of 50% and the world’s highest unemployment rate should leave its natural resources in the ground, lest it very fractionally contribute to carbon emissions.

That kind of talk is little more than foreign-funded environmental propaganda that exaggerates the environmental impact of oil and gas drilling, and tries to strong-arm poor countries into compensating for the continued exploitation of fossil fuels by the rich world.

Globally, fossil fuels still represent 82% of all primary energy consumption, and renewable energy makes up 6.7%. Of primary energy consumption, only 21% is electricity (though in South Africa, it’s 31%, which likely reflects the higher use of electricity instead of directly burning fuel for industrial heating applications).

Demand

Energy demand growth is decelerating globally, but not in Africa. Africa’s population will double by 2050, and only 13% of all Africans even have access to electricity.

Even in developed countries, it is clear that the age of fossil fuels is far from over. Developing countries cannot afford to leave their resources undeveloped merely to pander to the fears of domestic and foreign elites.

If Europe can consider gas, alongside nuclear, as a transitional fuel towards a clean energy transition, then why should Africa shun it?

The future, for oil in particular, would look bleak on an emissions reduction scenario targeting 1.5°C warming by 2100, but the world is not on that track, and appears to be aiming for 2.5°C, instead.

That means that future demand for oil may remain stable for longer than expected.

The disinvestment from Russia will lop 15% off the global gas supply, making gas look like a very attractive bet over the next decade or two.

As a continent, Africa produces 3.8%, or less than 3% (depending upon whom you believe) of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions, and South Africa only 1.3%. We are not the problem.

Emissions reduction

As fossil fuels go, gas is remarkable in that it produces virtually no pollutants, and far less carbon dioxide than coal. The US has long been a global leader in emission reduction, having cut its output by almost 20% since it peaked in 2005, and it achieved 61% of those emissions by switching from coal to gas.

According to energy research consultancy Wood Mackenzie, Africa is a hotspot for global LNG investments, and very substantial growth, especially in offshore LNG, is expected by the end of the decade.

Oil and gas majors remain nervous about Africa, however, especially as more projects are being developed onshore. Challenges range from a lack of established infrastructure and regulatory uncertainty to government instability and crime.

Open for business

South Africa should be the most attractive destination of all in Africa, and yet it has fallen behind. The most important way to mitigate risks for oil and gas majors is to shorten lead-times and offer quick approval processes, which is where South Africa is failing miserably.

The South African government must also become more competitive, not only with other African countries, but with global rivals. Greedy set-asides, large ‘empowerment’ shares, inflated royalties and price controls all harm the investment outlook for oil and gas projects.

As South Africa looks to climb out of its self-inflicted age of de-industrialisation, the need for energy – for transport, industry and electricity generation – will rapidly rise. So will its need for export revenues.

A thriving oil and gas sector will create thousands of direct and hundreds of thousands of indirect jobs, and contribute significantly to the over-burdened fiscus.

It’s time our government pulled up its socks, sidelined the obstructionists, and declared the country open for oil and gas business.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.