When we strip our conception of freedom from the community and the pursuit of the common good, we lose it.

I recently published a piece on Politicsweb, in which I argued that liberal democracy has shown a tendency to slide towards socialism, and that a conception of freedom that detaches the individual from responsibility within the context of the community is not freedom by any sustainable measure.

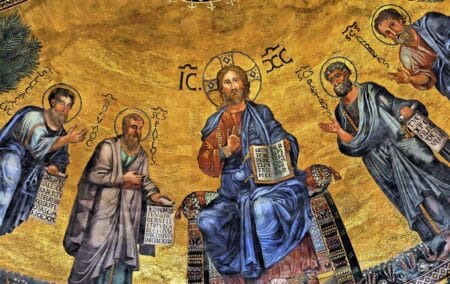

I referenced the apostle Paul who said that ‘indulging in the flesh’ is not an expression of freedom and the Roman consul and philosopher, Marcus Cicero, who said that we can only truly be free if we fulfil our responsibilities toward God, our communities, our descendants and our ancestors.

The responses by Ivo Vegter and Martin van Staden on the Daily Friend underline the importance of a continued discussion about the meaning of freedom and the balancing act between freedom for the individual and freedom for the community.

Vegter responded with the passion of someone whose religion was publicly ridiculed. Between all the name-calling and insults, he went as far as to suggest that people like me are tacit supporters of tyranny, oppression, apartheid and… you guessed it… Nazis! The hysterical reaction has deservedly attracted criticism. Responding to the details of Vegter’s article would require disentangling the vitriol from the substance.

Van Staden’s reaction was much more nuanced, and there is much to agree with. He concedes that there are indeed some pitfalls to liberal democracy, but continues to defend classical liberalism. He correctly argues that while social democracy and progressivism might only be accessible via a classical liberal offramp, these remain distinct things. He observes that my criticism was not merely with regard to liberal democracy – a criticism he shares – but also with regard to individualism – the point of disagreement. Unlike Vegter, who declares me his enemy, Van Staden remarks that there is much on which we can work together, and I agree. Van Staden also points out that liberal individualists like himself firmly believe in responsibility and obligation and that being a liberal doesn’t imply that you lose all sense of community.

Both Vegter and Van Staden took issue with my comments about individualism and disengagement, although Van Staden’s remarks are once again more mature. Vegter’s single biggest error is captured in the statement: ‘Roets mistakenly characterises the free individual as “disengaged”.’

Van Staden understands my argument to be that the result of liberalism is that the individual feels no sense of responsibility to the community. My argument was never that the free individual is disengaged, but rather that the disengaged individual is not free. Inversely: the free individual is an engaged individual. It is also not my claim that the result of liberalism is that individuals feel no sense of responsibility toward their communities, but rather that a conception of freedom framed exclusively in the realm of individual choice leads to disengagement from the community. To present this observation as an attack on individual freedom is simply false. It is, however, a plea for a more realistic appreciation of individual freedom.

My plea is that we ought to recognise that ideological individualism has a dark side and that presenting freedom as a licence for the individual to do whatever they want evidently results in the destruction of freedom.

Individual freedom within the context of the community

Much has been said about the necessity and utility of individual freedom. A political system in which individuals do not have the freedom to organise their lives would indeed and obviously be an oppressive system. It is undoubtedly true that we are all unique and that, as unique individuals, we each have something unique to contribute to the community. From a Christian perspective, we can say that we have each been blessed with a unique set of talents, and that we are under an obligation to develop these talents and utilise them for the greater good.

Herein lies an important difference between modern individualism and what might be described as a recognition of our individuality. Recognising and celebrating our individuality and encouraging people to express themselves and to contribute in their own unique ways according to their individual choices is perfectly normal, healthy and, I might add, necessary. Individuality becomes individualism however once it becomes an ideological quest, when the pursuit of individual freedom is not a recognition of what is natural anymore, but an ideological project; when it becomes a theory according to which we seek to organise the world, because we believe the world would become a better place once we subject it to our theory. When individualism leads us to believe that freedom is only the right of the individual to do what they want, the consequence is a detachment of the individual from its natural relationship with the community. This is because a natural consequence of community life is that it imposes certain limits on what we can do – not necessarily limits in the form of laws enforced by the state, but limits in terms of an agreement within the context of the community of what constitutes acceptable behaviour. Acceptable behaviour in the context of the community includes things we ought to do and things we ought not to do. Within this context individual freedom remains a fundamental component of freedom. However, once we conceive of freedom exclusively as individual choice, the consequence is that responsibility, community engagement and pressure for individual restraint become barriers to freedom, where these used to be regarded as crucial components on the road toward freedom.

This is why public intellectuals like Steven Pinker now claim that freedom includes the freedom to destroy our lives. Now we might ask: If freedom becomes the freedom to destroy our lives; if choosing to be a drug addict, a bad father, or to cheat on your wife is an expression of freedom merely because it is a consequence of ‘individual choice’, is freedom still worth fighting for?

This is precisely why Edmund Burke wrote in his Reflections on the Revolution in France that if the effect of freedom is that every individual can just do whatever pleases them, we would do well to see what pleases them before we risk congratulating them on their freedom. To strip our conception of freedom from a higher purpose and to reject virtue and the pursuit of the good as a component of freedom is to present freedom as nothing other than mere licentiousness. To present freedom as licentiousness is to deprive freedom of its status as the ultimate good. This is a corruption of freedom. This is precisely why the Bible says that when we succumb to our sinful desires, we are not free men, but slaves.

Freedom and the pursuit of what is good

G.K. Chesterton observed that the modern world has shown a strange tendency to shirk the problem of what is good: ‘The modern man says, “Let us leave all these arbitrary standards and embrace liberty.” This is, logically rendered, “Let us not decide what is good, but let it be considered good not to decide it.” He says, “Away with your old moral formulae; I am for progress.” This, logically stated, means, “Let us not settle what is good; but let us settle whether we are getting more of it.”’

The dodging of the discussion on what is good is fairly new, because the framing of freedom as exclusively in the realm of individual choice is fairly new. As a result, it became a violation of freedom when a community were to decide what is good.

Now, the question ‘what is good?’ can be answered in different ways. The Biblical answer is simple: God is good. As a result, the struggle against the dark side of our individual selves is good, and giving in to our sinful desires is not good. The problem here is that even the most faithful Christians remain sinners. Naturally, then, Christians do bad things. When Christians do bad things, atheists like Vegter enthusiastically use this as an argument against Christianity. One of the core messages of Christianity remains however a call to recognise that we are indeed fallible beings with a capacity to do evil, and a plea to combat these things, first and foremost within ourselves.

From a community perspective, the answer to the question ‘what is good?’ is not as easy. Our over-arching Western tradition teaches that communities ought to debate this question among themselves and within the context of the community. Different communities might reach different answers. This is why different groups (nations in particular) develop different cultures and traditions. The discussion on what is good for the community, however, is an ongoing discussion with regard to which every individual ought to take part, for their own good and that of the community.

Freedom through fulfillment

This modern, individualistic conception of freedom carries the seeds of its own destruction. With the advent of ideological individualism as the gold standard for freedom, we also witnessed the advent of selfishness, mistrust, emotional carelessness, ideological radicalisation, narcissism, anger, depression and a general sense of disillusionment. The disintegration of American politics over the last few decades is one case in point. The slide from individualism to socialism and the unexpected, yet powerful alliance between the Marxists and the post-modernists also prove this. This is also evident in the growing global backlash against liberal democracy, not to mention the alarming increase in suicide rates in much of the world.

But freedom is not mere self-centredness. Freedom is fulfilment in the pursuit of what is good, in cooperation with our fellow community citizens. Freedom is to recognise that we are fallible, sinful creatures that cannot achieve much by our individualistic selves, but that can achieve great things when we guard against our sinful impulses and we work together in the context of the community. It is the pursuit of what is objectively good, but also the respect not to impose our way of thinking on others because we disagree with their norms and customs. Freedom is mutual recognition and respect and the pursuit of peaceful coexistence between communities. Freedom is working together to achieve great things, not for ourselves, but for our descendants, just as our ancestors did before us. Freedom is what we achieve once we have done these things, but it is also what we experience while we do these things.

And if we disagree on what freedom is, that’s okay. We can still work together on the many issues on which we agree.

[Image: Apse mosaic of the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls (1220), Rome, depicting Christ flanked by the Apostles Peter, Paul, Andrew and Luke. Alberto Fernandez Fernandez, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10787624]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend