This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

28th June 1519 – Charles V is elected Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire

Portrait of Charles V, formerly attributed to Titian

Charles V is one of history’s most fascinating characters, in part because within his life we can see the transition from one epoch of history to another.

Remarkably, he was also known officially as Charles, by the grace of God, Holy Roman Emperor, forever August; King of Germany; King of Italy; King of all Spains, of Castile, Aragon, León, Navarra, Grenada, Toledo, Valencia, Galicia, Majorca, Sevilla, Cordova, Murcia, Jaén, Algarves, Algeciras, Gibraltar, and the Canary Islands; King of Two Sicilies, of Sardinia, Corsica; King of Jerusalem; King of the Western and Eastern Indies; Lord of the Islands and Main Ocean Sea; Archduke of Austria; Duke of Burgundy, Brabant, Lorraine, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Limburg, Luxembourg, Gelderland, Neopatria, and Württemberg; Landgrave of Alsace; Prince of Swabia, Asturia and Catalonia; Count of Flanders, Habsburg, Tyrol, Gorizia, Barcelona, Artois, Burgundy Palatine, Hainaut, Holland, Seeland, Ferrette, Kyburg, Namur, Roussillon, Cerdagne, Drenthe, and Zutphen; Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire, Burgau, Oristano and Gociano; and Lord of Frisia, the Wendish March, Pordenone, Biscay, Molin, Salins, Tripoli and Mechelen.

Born into the rising Habsburg dynasty in the year 1500, in Flanders – modern-day Belgium – to a Flemish Duke and a Spanish mother, Charles was at the heart of the aristocracy that ruled medieval Catholic Europe shortly before its shattering in the Protestant Reformation.

Raised in Flanders, Charles would in many ways epitomize the ultimate medieval king at a time when the Middle Ages were fading away and the modern era was truly beginning. Being a product of the international Catholic aristocracy, Charles is not easy to pigeonhole as being related to any modern nationality; growing up, he was influenced by Austrian, Dutch, Flemish, Spanish and French cultures.

A painting by Bernhard Strigel representing the extended Habsburg family, with a young Charles in the middle

At the age of six, Charles inherited the Duchy of Burgundy, which while it did not control the actual Duchy of Burgundy, it did rule over the western border of the Holy Roman Empire and the Low Countries.

While at first Charles was expected only to take the throne of the Duchy of Burgundy and perhaps the Archduchy of Austria, his Spanish mother went insane and her relatives failed to produce a male offspring to take the Spanish crown. So, in 1516, at the age of 16, Charles was made King of Spain.

A 1519 portrait of Charles V by Bernard van Orley, with the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece prominently displayed

Three years later, when he was 19, Charles’ paternal grandfather died, and Charles became the heir presumptive to the technically elected but often effectively hereditary title of Holy Roman Emperor, as well as its titles of King of Italy and King in Germany. As so, on 28 June 1519, Charles was elected as Holy Roman Emperor.

Pope Clement VII and Emperor Charles V on horseback under a canopy, a 1580 portrait by Jacopo Ligozzi depicting the entry of the Pope and the Emperor into Bologna in 1530 when Charles was crowned as Holy Roman Emperor by Clement VII.

This meant that by the time he was 20 he was ruler of a complex set of medieval titles across Europe which included the kingdoms that would be united into Spain, the possessions of the Spanish crown which included southern Italy, and Sardinia, as well as the border lands between modern France and Germany, modern Luxembourg, most of the low countries, the Duchy of Milan, Austria, the modern Czech Republic, parts of modern Hungary, Croatia and Slovakia, and various lands scattered across Germany.

It was an impressive haul, born of years of slow conquest and marriage alliances by his ancestors in the quintessentially medieval methods of expanding one’s lands.

However, the world was changing, and Europe had now reached out into the wider world beyond its borders and begun to establish the first truly global maritime empires.

Allegory of the reign of Charles V, a 16th-century painting by anonymous French painter. Charles V and his enemies (from left to right): Suleiman I, Pope Clemens VII, Francis I, the Duke of Cleves, the Duke of Saxony, and Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse

Following the trans-Atlantic expedition westward in 1492, Spain had come into possession of new territories in the Caribbean, and in 1521 Spanish adventurers would conquer the mighty Aztec Empire and its surrounds, adding modern-day Mexico and Central America to Charles’ territories. Before his death Charles would also come to rule over much of modern-day Venezuela, Columbia, Ecuador and Peru, following Spanish settlement of South America and the conquest of the Inca Empire.

This made Charles ruler of an empire which was truly global in scope, spanning three continents and able to draw on an incredible and diverse collection of resources and peoples for his use, and inferior in power only perhaps to the strength of the Ottoman Empire and the Ming Dynasty in China.

Portrait of Charles V with a dog, by Jakob Seisenegger (1532)

Despite holding this modern global empire as part of a world which was increasingly becoming globalised through expanding trade networks, Charles ruled his empire like a medieval king. Never really being concerned with the Americas that much, Charles spent his entire rule travelling around his possessions, as medieval monarchs would, rather than establishing a central capital from which to rule.

Holding together such a diverse collection of territories was difficult, however, and his entire reign into the 1550s was spent dealing with a number of crises. Wars with France, wars with the Ottoman Empire and most importantly perhaps the Protestant Reformation which began during his reign and would forever shatter the unity of the old medieval Catholic world.

The Americas too faced a crisis, as the Spanish conquerors and settlers abused and enslaved their new native American subjects, who – already ravaged by new European diseases – were greatly reduced in number. Charles tried several times during his reign to issue laws protecting his new non-Spanish subjects in the Americas, which he viewed as equal subjects worthy of his protection.

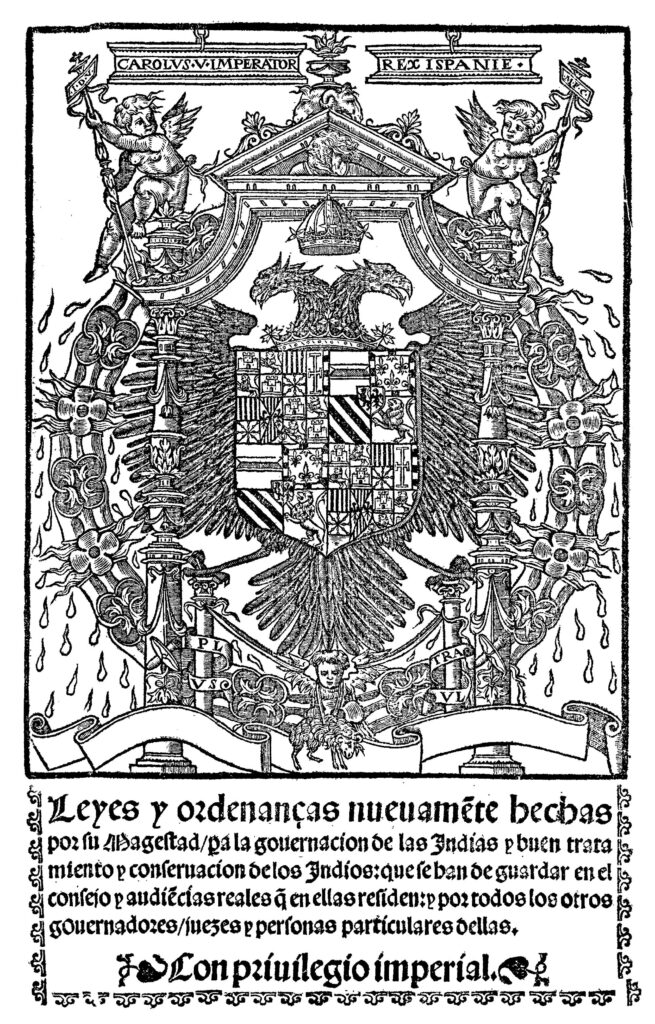

Frontispiece of the 1542 New Laws issued by Charles V, Emperor and King of Spain

But his need for silver from the New World and his general preoccupation with Europe prevented him from ever achieving these aims.

Ultimately the task of ruling such a complex empire was impossible; Charles would not contain the Protestant Reformation, and while he mostly contained France he would lose major conflicts with the Ottomans – though he did manage to drive them back from the first Ottoman siege of Vienna in 1529. Before his death in 1558, Charles abdicated his various thrones and titles, splitting the Habsburg Empire into Spanish and German halves. His reign also saw the explosion of inflation, which would ultimately cripple the Spanish crown and leave Spain falling behind its other western European competitors.

Allegory on the abdication of Emperor Charles V in Brussels, Frans Francken the Younger’s depiction of Charles V in the allegorical act of dividing the entire world between Philip II of Spain and Emperor Ferdinand I

Charles’ life remains a fascinating time, when the final embers of the medieval world burned away and the new modern age of global empires, national identities, and international trade networks began to take shape.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend