This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

30th June 1960 – Belgian Congo gains independence as Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville)

Map of the Belgian Congo published in the 1930s

The vast area which today forms the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) has a long history of human settlement and drama, only a fraction of which is known to us, due to the undeveloped nature of much of the country, its thick jungles, its tumultuous political history and its lack of written records.

Human activity in the DRC is dated to at least 90 000 years ago with the discovery of ancient fishing tools. While it is debated, it is likely that the first inhabitants of the DRC were the Twa or Batwa peoples, once commonly known as Pygmies due to their short stature (adult Twa men are usually less than 150 cm tall).

The Twa peoples mostly lived (and some communities of them still live) in the central and northern regions of the DRC, the areas with thick rainforest. Their genetic lineage diverged from other Africans around 100 000 years ago and they would have lived as hunter-gatherers.

Batwa people from Central Africa, representing four tribes, photographed at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition, or St Louis World’s Fair, in 1904. Photograph attributed to Jessie Tarbox Beals [https://picryl.com/media/pygmies-from-central-africa-representing-four-tribes-3-latuma-crown-prince-e66c6d]

Things would change when the Bantu peoples from south-eastern Nigeria and Cameroon began migrating into the region of the DRC around the 1st Millennium BC, probably sometime after 500 BC. The Bantu brought agriculture, pastoralism and, later, iron tools into the region.

The Twa were unable to compete with the Bantu, who, over centuries, enslaved, killed off or absorbed the Twa into their communities with the Twa adopting Bantu languages and many of the surviving populations continuing to live as the vassals of Bantu communities.

Most of the Bantu peoples in the DRC would be split into small settlements and tribal groupings, particularly in the north and central rainforests, as the difficult terrain and high rainfall limited agriculture and therefore limited population growth. The largest and most populous polities of the Bantu-speaking peoples would emerge in the southern regions of DRC, which is savannah grassland.

Around the 1300s there is evidence that the Bantu communities of the south developed into what we might recognise as feudal kingdoms, decentralised polities where local landowners ruled their area but appealed to a central king to resolve disputes among the nobility, and administer justice.

We begin to know much more about these kingdoms with the arrival of the Portuguese to the region, as they wrote accounts of the various peoples they encountered.

Kingdom of Kongo monarch João I Nzinga a Nkuwu

The most important kingdoms of this region, post European contact, were the Kingdom of Kongo, based in modern Angola with its eastern border stretching into modern DRC, the Kingdom of Lunda, the Kingdom of Kuba and the Luba Empire.

These kingdoms battled for control over the lands south of the rainforests and developed trade networks with the coasts, trading agricultural products, salt, iron ore, copper, and slaves.

The Kingdom of Kongo in particular became heavily invested in the salve trade, capturing hundreds of thousands of people from rival kingdoms and trading them to Europeans at the coast in exchange for alcohol, textiles, iron goods and firearms.

An early depiction of a Portuguese encounter with the Kongo royal family

This economy was similar in structure to that of the oil emirates in the modern world and as a result Kongo’s economy would go into irreversible decline when Europe banned the slave trade, beginning in the 1800s.

A Zanj slave gang in Zanzibar (1889)

By the late 1800s the kingdoms and tribes of Congo had fallen far behind their neighbours and were now far too weak to resist conquest. In the east of modern DRC, Muslim slave traders from the Islamised coastal regions of East Africa raided for slaves deep into the interior, and even established short-lived kingdoms.

Meanwhile the newly industrialised powers of Europe looked at Africa’s interior, as yet mostly untouched by Europeans, and saw opportunities for expansion.

Among these was King Leopold II of Belgium, who sought personal prestige and power in the form of a colony for himself. As discussions ramped up between the European powers about how to divide up the continent, Leopold ran a publicity campaign to cast himself as a great humanitarian who wanted to work to civilise Africa, do humanitarian work and put an end to the Muslim slave trade in the Congo.

Leopold II, King of the Belgians and de facto owner of the Congo Free State from 1885 to 1908

His true goals were in fact far more cynical and self-serving. As he himself remarked to an aide in London: ‘I do not want to risk … losing a fine chance to secure for ourselves a slice of this magnificent African cake.’

The Berlin Conference, as illustrated in Illustrirte Zeitung

At the Berlin Conference in November of 1884, Leopold’s campaign paid off and he was given the entire region of modern DRC as his personal territory.

It would not be a Belgian colony but rather a kingdom ruled by Leopold which he would call the Congo Free State. Leopold soon set to work, sending explorers and troops into his new territory to secure the submission of local African chiefs and kings.

Cartoon depicting Leopold II and other imperial powers at the Berlin Conference

Completely outmatched in military and economic power, and with promises that they would retain much of their previous status, rulers across the Congo Free State quickly signed treaties submitting themselves to Leopold, with those who didn’t often being speedily replaced by more Leopold-friendly rulers. Within a few years of each other the territory of the Kingdom of Lunda, the Kingdom of Kuba and the Luba Empire were all absorbed into the Congo Free State or one of the surrounding European empires.

The Congo Free State, however, soon collapsed financially and, in an effort to return a profit on the enterprise, Leopold would attempt to turn the entire country into a giant rubber-extraction plantation.

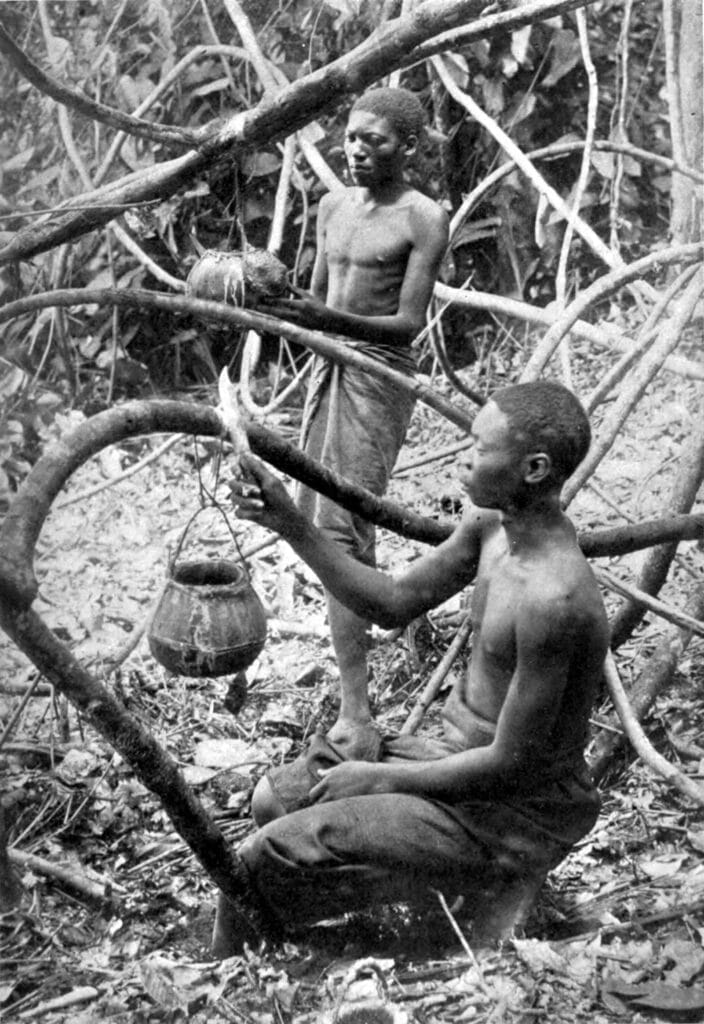

Congolese labourers tapping rubber near Lusambo in Kasai

What followed is regarded as the worst example of European colonialism in Africa, with millions being forced under a harsh labour regime to extract as much rubber from local rubber trees as possible.

Penalties for not meeting rubber-extraction quotas were extreme, including execution or mutilation, infamously the chopping off of hands. Other methods included the taking of hostages in order to ensure compliance.

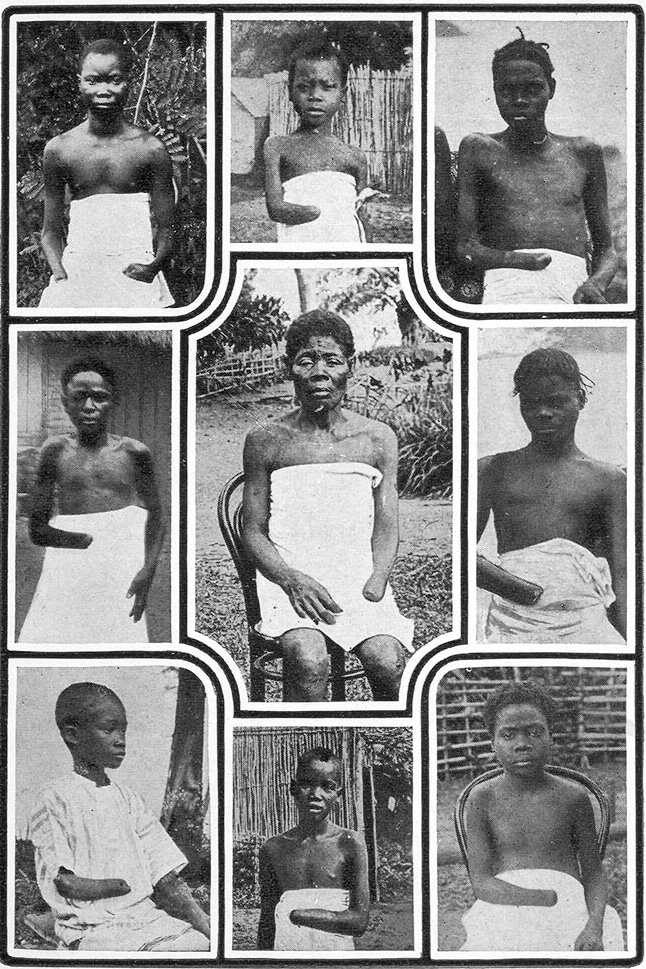

Children mutilated during King Leopold II’s rule

Famine and disease also sky-rocketed as new diseases were brought into the interior of the Congo by trade with the outside world, and as the manpower needed to grow food was drawn away to meet the demands of rubber extraction. It is unknown how many people died as a result of Leopold’s governance, but estimates range from two million to 20 million – possibly around half of the region’s population.

The horrors of the Congo Free State quickly came to the attention of the wider world, with many books and articles being published drawing attention to the atrocities.

Most famous among these were Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Crime of the Congo.

Things came to a head when Belgium’s main ally, the British Empire, published a report from its local consulate, the Casement Report, in 1904. This detailing of the abuses and the outrage that followed forced Leopold to set up an independent commission of enquiry, whose findings were much like those of the Casement Report.

The growing outrage would force a reluctant Belgian government to annex the Congo Free State in 1908, as the colony of the Belgian Congo.

The former Ministry of the Colonies, to the left of the Constitutional Court in Brussels [Michielverbeek, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47754687]

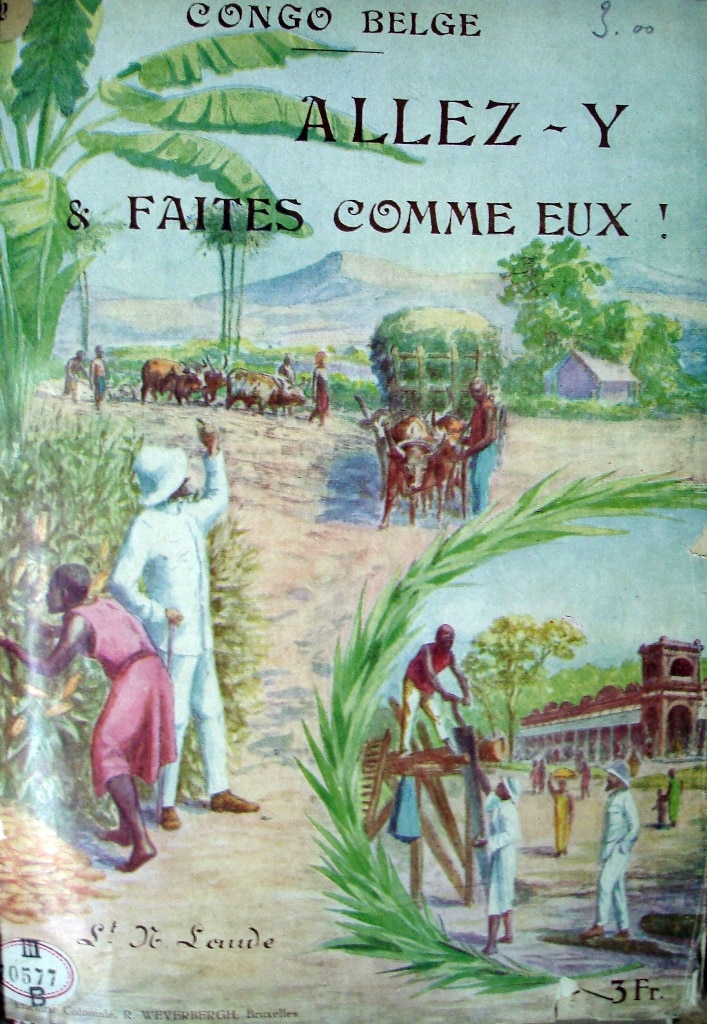

Conditions would somewhat improve after the annexation, with the Belgian government trying to crack down on forced labour. But while it was now officially illegal, widespread use of forced labour continued in the colony.

The new colonial administration expanded education, missionary work, and built more infrastructure than Leopold had.

Propaganda leaflet produced by the Ministry of the Colonies in the early 1920s

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the local Congolese elites began to demand independence. Belgium began slowly to move towards granting the colony more autonomy and control, with eventual possible independence, but was overtaken by events. In 1959 a series of extensive riots took place in the capital, Léopoldville, and the Belgians decided that they were no longer willing to continue holding on to the colony.

While Belgium envisioned a slow multiple-year transition to independence, the advocates of Congolese independence pushed for immediate withdrawal.

In the face of fierce advocacy from local elites, local tax boycotts, rioting and other forms of rebellion, the Belgian authorities decided to cut and run. Independence was granted on 30 June 1960.

President Joseph Kasa-Vubu and Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba join other dignitaries at the independence ceremony on 30 June 1960

Within days chaos would break out across the Congo with police officers and local militias targeting Belgians and other European people still living or working in the Congo in an event known as the Congo Crisis.

A staged photograph during an operation to rescue Western hostages held in Stanleyville during the Congo Crisis in late November 1965 (The Belgian paracommando was asked to pose on the pavement by a photographer at the scene. The hostages in the photograph were killed minutes before the troops arrived.)

The war against the Europeans would devolve into a civil war between federalists who wanted a more federal and decentralised Congo and Centralists who wanted to centralise power in the capital.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend