‘They must branch out into other occupations and become clerks, roadworkers and fitters and turners. I am sick and tired of seeing young Indians sitting on shop counters as if there were no other occupations open to them. Should they fail to do so willingly, I will be forced to take action. The day will come when we will have to reconsider the whole matter of trading licences.’

These were the sentiments of Blaar Coetzee, then Minister of Planning, in 1968.

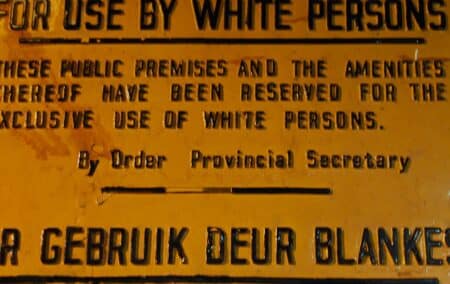

The context, obviously, was the racial ordering of the South African economy under apartheid. Government policy was geared to maintaining a distribution of economic opportunities and outcomes to the approval of the state; this was defined as ‘a positive method of promoting the orderly living together of the races.’

To this end, to ensure that people were slotted appropriately into their officially determined slots, the government of the day was willing to ruin and retard lives, overriding not only decency but rationality too.

In 1970, an engineering firm in Germiston was found to have engaged three Africans to operate machinery. The proprietor – one SA De Klerk – protested that he had advertised the positions far and wide, but the white applicants were of an ‘unreliable, shiftless type’, so he’d entrusted the job to African employees. His firm was fined nonetheless. After all, it was the state’s position that society should reflect its ideological predispositions, and the role of its subjects was to comport themselves accordingly, consequences be damned.

The state would (and frequently did) ‘take action’.

History repeats itself in South Africa. In early April, President Ramaphosa signed into law the Employment Equity Amendment Act; this empowered the Minister of Employment and Labour to set racial ‘targets’ – quotas in all but name – that firms employing over 50 people would need to meet, on pain of fines that could put offending firms out of business. This was followed in short order by the sectoral ‘targets’, which attracted considerable attention.

Sloppy officious mindset

A product of the sloppily officious mindset that characterises so much of the present-day South African state, these are measures motivated by ideology and designed for the convenience of a bureaucracy that exists now above all to perpetuate itself.

Much attention has been paid to the pedantically detailed – though sometimes mathematically incoherent – nature of the regulations. In KwaZulu-Natal, firms are to pursue 0.2% coloured male and 1.9% white female representation at top management level over a five-year period. Manufacturing firms in Limpopo will have to strive for 0.0% coloured female and 1.2% white male representation at the skilled level. Presumably, echoing Minister Coetzee’s thinking, those surplus to the requirements of the state’s ‘targets’ would need to ‘branch out’ across the country or the economy.

None of this is practicable. Not only is South Africa a low-growth economy, but too much of its workforce is inadequately skilled – even by minimal standards of literacy and numeracy, as recent international benchmarking has indicated – for the demands of a contemporary economy. This reflects the sad legacy of South Africa’s apartheid past, but also the monumental failures of the post-apartheid era.

Nor is it apparent just how staff can be shuffled around to meet these demands. The courts have observed that affirmative action is not a sufficient ground for retrenchment, so look out for some pushback from ordinary people too concerned with making a living to see their superfluity to the transformation project. (In other words, more or less what millions of South Africans did during apartheid ….)

But, equally, expect the labour bureaucracy to try and enforce its writ. Employment and Labour Minister Thulas Nxesi promised in 2019 that the government would ‘start to be very harsh’ on employers who failed to meet the government’s requirements. With fines of up to 10% of turnover, it has signalled that it would be prepared to destroy non-compliant firms.

One moderate saving grace is that smaller firms are exempt from this. This is a blessing, as small businesses have a tough enough time of it in South Africa. This law will be every incentive they need to stay small.

None of this matters

It can confidently be said that none of this matters to those responsible for pushing this legislation. They demand an outcome that can fit into a worldview and onto a spreadsheet (complete with fractions of people, where the authorities are ‘sick and tired’ of seeing particular people in particular jobs).

Above all, in threatening firms’ existence and further disincentivising the creation of jobs, the government discounts the interests of the 7.9 million unemployed (2023 figures), and in particular those of the 1.7 million unemployed who are 24 and younger. (That’s by the so-called official definition; taking into account those no longer actively seeking work, the numbers balloon to 12.3 million and 2.3 million, respectively.)

That is a catastrophe by any definition. Each individual unable to find work represents frustrated hopes and lost opportunities. These are real human beings, not statistical abstractions. But South African officialdom has a lamentable tradition of failing to grasp that. Just ask SA De Klerk, or Blaar Coetzee. Or Thulas Nxesi.

[Image: Mulungu95, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23828908]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend