The first two decades of the 21st century saw an alarming reversal of a 150-year trend towards greater economic freedom.

I frequently reference the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World Index. It has faced some criticism over the selection and measurement of its criteria, but it offers a unique view of the virtues of economic freedom since 1970.

It convincingly documents that nations that are economically free outperform their non-free counterparts not only in terms of per-capita GDP, but on almost any indicator of well-being you care to name, including poverty levels and poverty rates.

In its latest report it found that despite the pandemic response having wiped out about a decade’s worth of improvement in economic freedom in the world, the average in 2020 was still higher than in 2000.

New analysis

A new analysis by economic historian Leandro Prados de la Escosura, however, disputes this finding, and it makes for worrying reading.

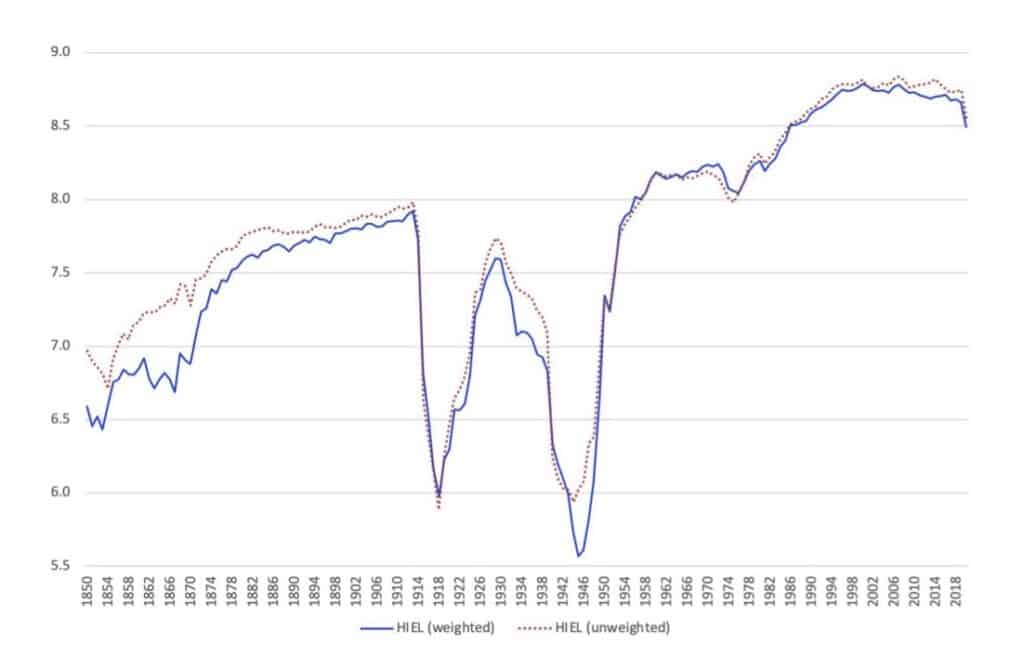

Prados de la Escosura extends the historical data back to 1850, at the expense of having fewer countries in the sample.

He follows the Fraser Institute in selecting as the dimensions of economic freedom the legal system and property rights, sound money, openness to international trade, and the regulatory burden, but omits the size of government from his analysis.

He argues that freedom of economic activity implies ‘freedom under the law, not the absence of all government action’, to quote influential free-market economist Friedrich Hayek.

‘In fact’, writes Prados de la Escosura, ‘the government, as a provider of protection to the individual from coercion, is essential for economic liberty. It is the nature of government action, rather than how active the government is, that is at stake. Hence, the size of government should not be considered a dimension of economic freedom.’

I agree with Hayek that the nature of government action is what matters most to economic freedom, but I’m not sure I agree that this should mean omitting the size of government from economic freedom indices. As the Fraser Institute measures economic freedom, it includes important factors such as the size and extent of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The more the economy is absorbed and controlled by SOEs, the less of it remains free to the private citizenry. As we see in South Africa, this has a substantially negative impact on both economic freedom and prosperity.

Peering back

Be that as it may, with the Historical Index of Economic Liberty that Prados de la Escosura constructs, he peers far further back than 1970. He offers a rare glimpse at how economic freedom has changed in the last 170 years, reaching all the way back to 1850, during the first industrial revolution.

What immediately jumps out is that improvements in economic freedom have been very consistent, except during the First World War and the period between 1930 and the end of the Second World War. There was a blip around the time of the US Civil War, and another in the dismal 1970s, but otherwise, economic freedom has been on a relentless march.

It has brought constant improvements in GDP per capita. Data is sparse before 1950 outside the developed world, but the decadal data provided by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) shows a high correlation between rising economic freedom and rising GDP per capita, with the latter showing significant slowdowns or minor reversals only during the decades in which the two World Wars fell.

As the Fraser Index makes clear, the positive impact of economic freedom is not limited to GDP per capita. Prosperity buys a great many things, including better education, better healthcare, better poverty alleviation, better equal rights, and a host of other quality-of-life improvements.

The correlation between a composite measure of human development and GDP per capita demonstrates that while life isn’t all about money, money buys improved quality of life.

Reversal

Now, let’s return to Prados de la Escosura’s analysis. The alarming finding is that the rise in economic freedom halted, and then began to reverse, around the year 2000.

There are many reasons for this. Sound money has been a significant driver of economic freedom, so lax monetary policy, with low interest rates and extensive use of quantitative easing (i.e. money printing), would have contributed to a decline in economic freedom.

The heydays of global free trade are long gone. There has been a steep change in the growth of global export volumes, which peaked in 2008 and again in 2010, but since then has grown at only about half the rate that it did before.

The youth, going back to the Battle of Seattle of 1999 and similar anti-globalisation protests, haven’t a clue how hard their elders fought for the prosperity and relative peace that came with global free trade.

They lean heavily to the left now, and the self-interest that free market capitalism harnesses for the common good becomes mere selfishness in the view of socialists.

With the rise of nationalist movements and populist governments, many countries have turned away from free trade, and have given in to the demands of domestic special interests to institute trade protections against foreign competition.

Then there’s a rising demand to impose regulations and restrictions on economic actors, so as to minimise actual and imagined risks to the public. That external risk mitigation comes at a huge cost in terms of rising prices, lower economic vitality and reduced innovation.

Lost gains

According to Prados de la Escosura’s numbers, by 2020 – that is, before the pandemic – the world had already lost all the economic freedom gains it had made between 1986 and 2000. The next stop is levels last seen 40, 50 or 60 years ago.

With such a significant decline in economic freedom, a commensurate decline in other indicators of well-being, particularly in GDP per capita, will surely follow.

Economic freedom has brought the world untold prosperity. Where people are free, and markets are free, their hard work has without fail delivered greatly improved quality of life.

Africa is the last continent that has yet to taste true economic freedom. That is why it is the poorest continent on Earth. Africa cannot prosper without free economies, free markets and free trade. Without economic freedom, lasting progress will forever elude the continent.

Africa leading

A global decline in economic freedom is therefore doubly alarming, when viewed from the southern tip of Africa.

It would be great if a new generation of young Africans can show the world that economic freedom was not just some fancy that went out of style with the retirement of the boomers.

Africa has tasted the very socialism that the younger generations in the rich world now espouse. This continent can lead the world into a new era of prosperity by following the principles of free enterprise and free markets.

Image: Editorial cartoon ca. 1910 in the public domain, courtesy of the London School of Economics and Political Science 2007 Miscellaneous Collection.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.