The release of treated water from the stricken Fukushima nuclear power plant has raised entirely baseless fears.

The three nuclear meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, as a result of the Great Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, reignited irrational global fears about nuclear power back in 2011.

It led to widespread over-reaction, public opposition to nuclear power, and the exceedingly unwise decision of some countries, notably Germany, to decommission their nuclear fleets.

Now, 12 years later, the release into the Pacific Ocean of treated wastewater from the Fukushima plant has revived those fears. Radioactive wastewater! In the sea! Where the seafood swims!

Say the word ‘radiation’, and people who understand little about the subject quake in their boots. Decades of fear-mongering science fiction tales of glowing mutants, and a misguided association between controlled nuclear fission in a power plant and nuclear weapons, have instilled a deep-seated but almost wholly irrational fear in the general public.

Extraordinary safety

The Fukushima accident on 11 March 2011, despite releasing radioactive material into the environment, has caused remarkably little harm. Two plant workers died as a consequence of the tsunami, but nobody died of acute radiation exposure.

To date, only four cases of cancer among plant workers, of which one resulted in a lung cancer death in 2018, have been linked to the meltdowns.

There is no documented evidence that any members of the public were harmed by nuclear radiation exposure.

By contrast, the panicked evacuation caused between 1 500 and 2 000 deaths, many due to exposure to icy weather. This was a higher death toll than the earthquake and tsunami originally caused in the affected area.

The Fukushima disaster is a testament to the extraordinary safety of nuclear power.

The Daiichi plant (‘daiichi’ means ‘number one’) was an old design, commissioned in 1971. It was one of the largest nuclear power stations in the world, producing 4.7GW of electricity. It was poorly maintained by a company known to have cut corners. It was struck first by the largest earthquake ever recorded in Japan (and the fourth largest ever recorded anywhere), and then by a 40-metre tsunami. Both events significantly exceeded the design capacity of the power plant. The earthquake led to three hydrogen explosions, severely damaging the plant, while the tsunami washed away multiple layers of backup power, resulting in a loss of cooling, which in turn led to the meltdown of three of the plant’s six boiling water reactors.

Yet only a single death could be attributed to radiation exposure in the subsequent 12 years.

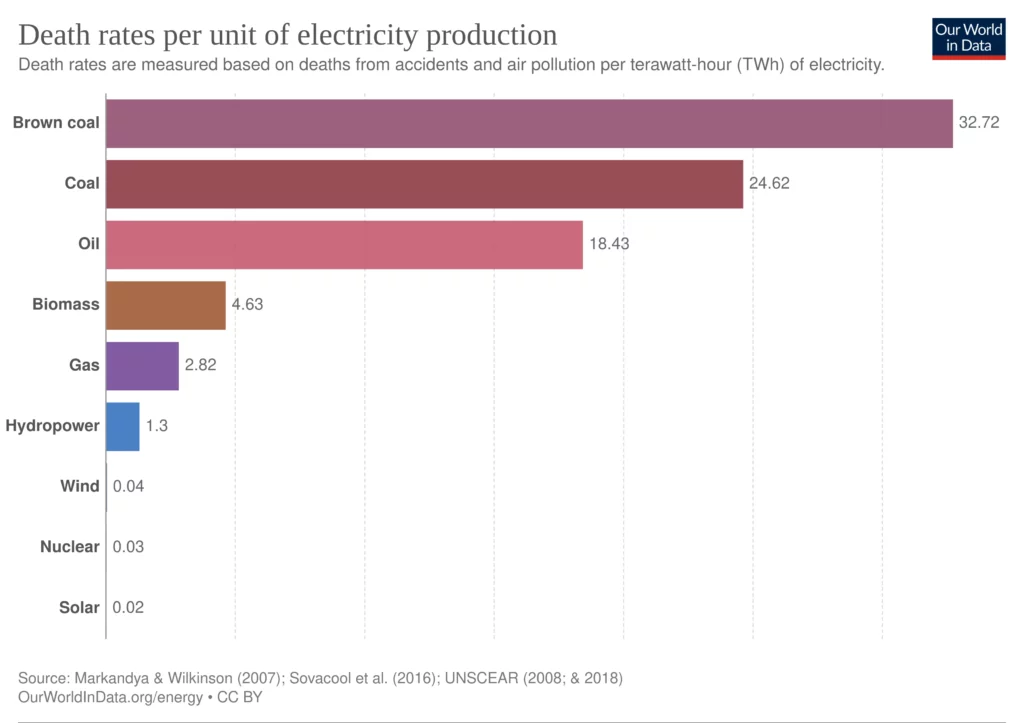

This serves to confirm the extraordinary safety record of nuclear power. Despite the far more serious Chernobyl incident of 1986, which remains the only nuclear power accident in history with a significant death toll, nuclear energy remains by far one of the safest forms of energy in terms of deaths from accidents and air pollution per unit of electricity produced.

(As an aside, considering that nuclear energy is reliable and dispatchable on demand, unlike wind and solar power, this makes nuclear by far the best zero-emission and zero-pollution energy source.)

Wastewater release

With that as background, we were recently treated to fearful news headlines over the safety, or otherwise, of the discharge of ‘radioactive wastewater’ from the stricken plant into the Pacific Ocean.

Note that none of the headlines said it is safe (which it is, as we’ll see). They raised fears, instead.

‘How worried should we be?’ asked National Geographic. Its article gives many rather flimsy reasons to be concerned, quoting only two marine scientists who expressed doubts about the claims of Japan, the United States, and the United Nations’ International Atomic Energy Agency that the release is in line with global practice and poses no significant risks.

An article in The Guardian eventually concludes that the release does not pose a health risk at all, but not before quoting Greenpeace, which is ideologically opposed to nuclear power and pulled out all the stops to blacken its reputation once again.

Others, too, sowed doubt in their headlines, only pointing out some way down the story, when most people have stopped reading, that the impact will be ‘vanishingly small’ and that the discharge water is probably safer than drinking water, before concluding that nonetheless, some people are afraid of the potential risks.

The facts

For the last 12 years, contaminated water has been stored on-site at the defunct Fukushima Daiichi plant. The water comes from continued cooling of the damaged reactor cores, as well as from local groundwater inflow that became contaminated.

Quarantining this water required over 1 000 tanks, to store a total of 1.25 million metric tons of water.

This water has since been treated, by means of an Advanced Liquid Processing System, This process removes all radioactive contaminants from the water, with the sole exception of tritium, which cannot be removed from water on an industrial scale.

Tritium is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen (3H, containing one proton and two neutrons). It has a half-life of 12.3 years, and decays into helium-3 via beta-minus decay.

The low-energy beta particles emitted in this process are largely harmless. They can penetrate only 6mm of air, are easily blocked by a piece of paper, and cannot get through the dead outer layer of human skin.

If ingested in high quantities, tritium could do a modest amount of harm, but it has a biological half-life of only seven to 14 days, and it does not bio-accumulate.

Tritium is safe enough that it is routinely used in the manufacture of radioluminescent wristwatch faces, exit signs, in rifle sights and other applications where self-powered lighting is required.

If you read the news reports, you’d think the Fukushima plant has tons of tritium to dispose of. In truth, a 2016 report found that the total amount of tritium in (what was then) 820 000 tons of water was a mere 2.1 grams.

Dilution

The SI unit for the concentration of radioactivity in water is Becquerels per litre (Bq/l). A single Becquerel represents one decay event per second. It does not distinguish between different types of radioactive decay, nor does it reflect how energetic decay events are. Either way, it is an extraordinarily small amount of radiation, and it usually comes with prefixes to refer to thousands, millions, billions, or trillions of Becquerels.

In 2016, the concentration of tritium in the treated Fukushima water was between 0.3 million and 3.3 million Bq/l. By now, that will have decayed to a maximum of about 2.4 million Bq/l.

The Japanese plan is to release all the treated water held at Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean over a period of 30 years, first diluting it to a concentration below 1 500 Bq/l. Once released, it will dilute much, much further, to negligible concentrations virtually indistinguishable from the natural background levels of tritium in ocean water of 0.24 Bq/l.

The World Health Organisation standard for the maximum concentration of tritium in drinking water is 10 000 Bq/l. (Other radioactive elements commonly found in drinking water, like radium, uranium and thorium, have much lower limits, because their decay is far more energetic. Their radioactivity typically overwhelms that of tritium by several orders of magnitude.)

Even if all the Fukushima water was released in a single year, instead of over three decades, the exposure risk wouldn’t reach one thousandth of the annual background radiation to which we are exposed naturally.

The discharge water will likely be more pure, and less radioactive, than most natural spring waters. ‘In theory, you could drink this water,’ James Smith, professor of environment and geological sciences with Portsmouth University, told the BBC.

The opposition

Leading the opposition to the water release are China, local fishers, and some Pacific island states, though the latter are divided on the issue.

The local fishers have a case, not because their fish will get contaminated, but because they will suffer from boycotts whipped up by environmental alarmists and China.

As it is, Japan’s national limit for radioactivity in food is 100 Bq/kg. For seafood from the Fukushima region, it was lowered to only 50 Bq/kg, in order to quell consumer fears. These limits are extremely low, compared with limits of 1 250 Bq/kg in the EU and 1 200 in the US.

Japanese fish, even from Fukushima, is extraordinarily safe, by global standards.

The Pacific islanders don’t have a case at all. They suffered historic trauma as a result of widespread nuclear bomb testing in the 1950s and 1960s, which has biased their populations heavily against nuclear radiation exposure of any kind. Their fear about this water discharge, hundreds or thousands of kilometres from their shores, is entirely irrational.

Which brings us to China. The Chinese have a great historical antipathy towards the Japanese, having suffered brutal wars and cruel occupations. Hate would not be too strong a word for it.

It is, therefore, no surprise that the Chinese Communist Party, through the state-owned media, is whipping up public hysteria and opposition to Japan’s plans. It fits entirely with the propaganda message that depicts the world outside China’s borders as dangerous, hostile, reckless and chaotic.

The Chinese government has banned Japanese seafood imports, and there are calls for wider consumer boycotts against Japanese products. The ruling party has encouraged a campaign to have thousands of individual Chinese citizens harass random Japanese businesses, local governments and schools with complaints about the Fukushima water release.

The state-owned media has also taken out advertisements on Facebook and Instagram, in multiple languages in multiple countries, denouncing the water discharge. They’ve turned this into a global propaganda campaign.

Disinformation

As one might expect, however, the Chinese stance is supremely dishonest and hypocritical.

Releasing water containing tritium is routine at nuclear power stations. As the UK government made clear in its statement of support for the Japanese plan: ‘The UK wishes to underscore the routine nature of aqueous discharges of tritium. It is standard practice throughout the nuclear industry globally.’

China has 51 operational nuclear reactors, and 21 under construction. In 2021, 13 of those reactors each released more tritium into the sea than the Fukushima water release programme will discharge in a year. Just one of them, the Qinshan power plant in Zhejiang Province, released 218 trillion Bq in 2021, 10 times as much as the annual cap of 22 trillion Bq planned for the Fukushima discharge.

Yet the Chinese foreign ministry issued a statement that is riddled with lies. Ignoring the tritium releases by its own nuclear power stations, it claims, falsely, that there are no precedents or standards for discharging tritium from nuclear power stations.

‘By dumping the water into the ocean, Japan is spreading the risks to the rest of the world and passing an open wound onto the future generations of humanity,’ it said. ‘By doing so, Japan has turned itself into a saboteur of the ecological system and polluter of the global marine environment.’

But China’s own discharges of far more tritium are hunky-dory? It is clear that we can’t trust the Chinese Communist Party.

It is also not surprising to find the Chinese government liars and the radical environmentalists at Greenpeace on the same side of this matter. The same is true for Anonymous, the amorphous collective of hippie hackers who conducted ‘hacktivism’ campaigns against Japanese entities.

The US has described China’s position vis-à-vis Japan as ‘economic coercion’.

Analysts have described it as disinformation designed to further China’s geopolitical rivalry against Japan.

The real risk

Disinformation is not harmless. It undermines trust in science, technology and safety regulations. It is rooted in vested interests, political chicanery, and a lack of understanding of radiation.

Those who fear any amount of radiation ought to consider why the US Domestic Nuclear Detection Office, which keeps a watchful eye over container movements at its ports, is concerned about ‘false positives’ from containers filled with ceramics, cat litter and bananas.

Radiation is all around us, naturally. It is in the soil of our gardens and the walls of our houses. It is in our vegetables and our meat. It is in the water we drink and the air we breathe. It comes at us from the sky. We are radioactive, thanks primarily to potassium-40 and carbon-14 isotopes we consume and that accumulate in our bodies.

Large amounts of radioactivity can cause damage, but small, diffuse amounts do not. Fish from Fukushima, and the tritium discharge programme, aren’t going to make an iota of difference to our exposure.

Disinformation and fear born of ignorance are major obstacles to public support for nuclear energy as a safe, reliable and clean form of energy that requires less land than renewable energy technologies and produces far less (and better-managed) waste than comparable fossil energy sources.

They are a major factor in the hyper-cautious over-regulation of nuclear energy, which makes nuclear energy far more expensive than it needs to be.

Countries that have turned their backs on nuclear energy, like Germany, have instead turned to dirty coal-fired power plants to save them from unreliable renewables. Coal-fired power plants, unlike nuclear power plants, do routinely kill people.

This is the perverse future to which nuclear disinformation and irrational fear can lead. Let’s not follow the hysterical masses there.

[Image: Greg Webb / IAEA. Workers at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station work among underground water storage pools on 17 April 2013. Two types of above-ground storage tanks rise in the background.]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend