In life, things are rarely simple. It is not often that any issue or situation can be seen in simple black-or-white or either-or terms, where nuance is an enemy rather than a friend.

But one situation which to me falls into the straightforward black-or-white camp is the current invasion of Ukraine by Russia. To me, as an outside observer, this seems to be a cut-and-dried issue where there are clear good guys and bad guys, which is rare in international relations.

To me it seems clear that Vladimir Putin is a totalitarian expansionist who is trying to resurrect the old Russian Empire by reclaiming its lost lands, with Putin seeing himself as a new tsar. Others, however, say that this is a justified reaction to the expansion of NATO, the Western military alliance, with the possibility of Ukraine joining the body being a step too far. This, coupled with alleged murders of ethnic Russians in the east of Ukraine, saw Putin’s hand forced. He invaded Ukraine to protect ethnic Russians and overthrow a regime of alleged Nazis in Kiev, the capital of Ukraine.

Some commentators also argue that Putin is a protector of Western values, with Moscow standing as a bulwark against Godless wokeism (this despite average church attendance and belief in the Christian God being lower than in most of the increasingly irreligious West).

But recently I was lucky enough to travel to Georgia, a country which is in a similar position to Ukraine. It is also a part of the former Soviet Union (indeed, the Soviet Union’s most infamous leader, Joseph Stalin, was a Georgian), and it fought a war with Russia in 2008. The struggle between Georgia and Russia is now what is described as a ‘frozen conflict’ by political scientists, one where hostilities have ended but no formal peace treaty has been signed, and with Russia still occupying about one-fifth of Georgian territory.

NATO

Relations between Georgia and Russia have been deteriorating since the early part of the century, after Vladimir Putin came to power and a pro-Western government came to power in Tbilisi, the Georgian capital. Following the announcement in 2008 that Georgia would be considered for full membership of NATO, Russia invaded the country, euphemistically calling it a ‘peace operation’, not unlike the ‘special military operation’ Moscow claims it is undertaking in Ukraine.

A number of major Georgian cities were occupied, Tbilisi was bombed, and Georgians were ethnically cleansed from villages in the north of the country before a ceasefire was declared after five days of fighting.

Robert Kagan, an American academic, said at the time that Russia’s willingness to use force against an independent country marked the ‘official return to history,’ referencing Francis Fukuyama’s famous declaration at the end of the Cold War that we had reached the ‘end of history’.

Since then, Georgia has oscillated between being pulled into the Western and Soviet spheres of influence. While it would seem that most Georgians would prefer to orient themselves to the West, given the evidence I saw in Tbilisi, successive Georgian governments in recent years, especially in the past 18 months, have generally seemed to prefer a thaw in relations between Georgia and its former coloniser, Russia.

According to polls, about three-quarters of Georgians are pro-Western, compared to a much smaller proportion who consider themselves pro-Russian. At the same time, nearly 90% of Georgians said Russia was the country that posed the greatest threat to it, with large proportions of Georgians saying Russians shouldn’t even be allowed into their country until the territory it occupies has been returned to Georgia.

Further evidence of the overall broad pro-Western slant in Georgia is that in a referendum held in 2008, nearly 80% of Georgians supported Georgian membership of NATO.

Realpolitik

Some of the rapprochement between Tbilisi and Moscow may simply be realpolitik by Georgian politicians, who are concerned that following the Ukrainian invasion, Moscow may decide to finish the job it started in 2008 in the Caucasus.

But if one had to judge simply from the graffiti in Georgia and the number of Ukrainian flags on display – in murals or on flagpoles – there is no doubt where the loyalties of the people of Georgia, or at least the inhabitants of Tbilisi lie.

Ukrainian flags are common across the city, both graffiti flags and cloth flags being displayed in various ways. In addition, graffiti, with various permutations saying basically: ‘Russian go home’ are a common sight in Tbilisi.

Another common sight across the city are European Union flags, making it clear what the long-term ambitions of many Georgians are.

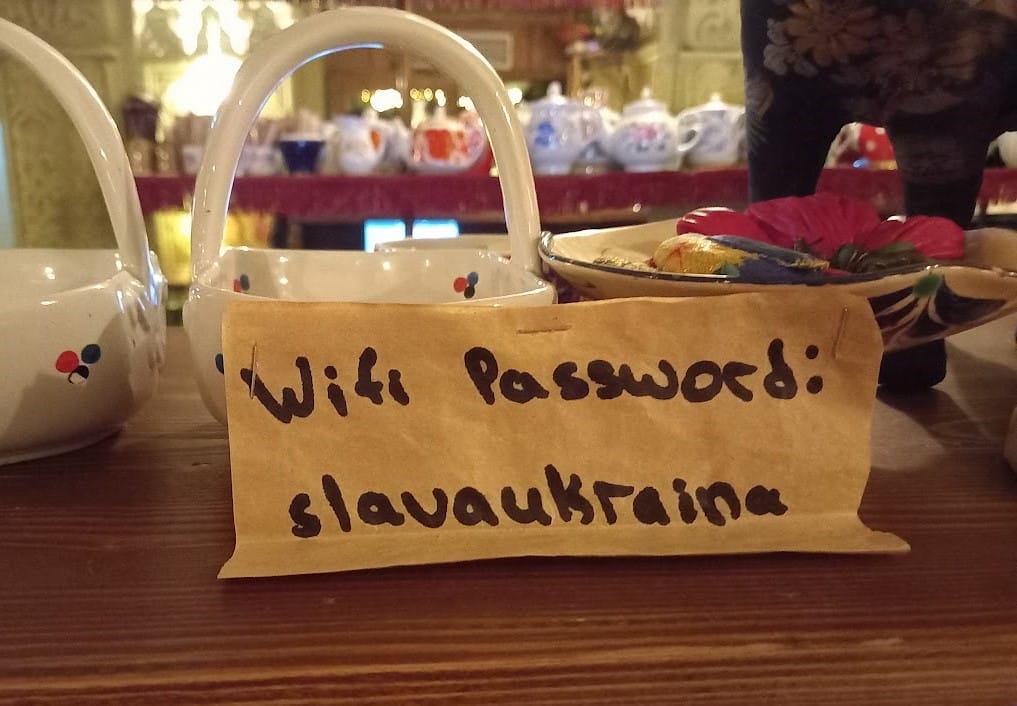

In another restaurant, a sign at the counter says that the establishment’s wi-fi password is ‘slavaukraina,’ meaning ‘Glory to Ukraine’.

In the same restaurant, at the bottom of the bill there is a small factoid, telling patrons that 20% of Georgian territory is occupied by Russians.

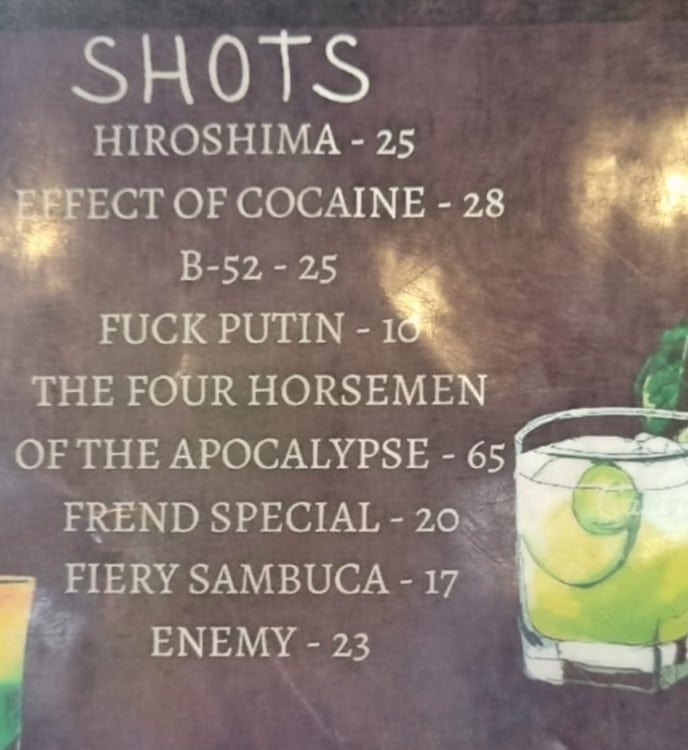

In a quaint bar close to the city’s cable car station which is housed in a refurbished tram, there is a shooter called the ‘Fuck Putin’.

Its ingredients are vodka, peach juice, and blue curaçao, with the colours of the drink reminiscent of the Ukrainian flag, as the main image at the top shows.

Georgians are generally conservative and religious, with priests from the Georgian Orthodox Church in their full regalia a regular sight in Tbilisi. There are churches across the city, and even during the week they are relatively full, with people reflecting quietly in the pews. One would think that if Putin and the Russian state were the great protectors of Western civilisation, as some would have us believe, Georgians would have welcomed the Russian excursion with open arms. Instead, Georgians continue to orient themselves to the West, away from Moscow.

Dying horse of Russian imperialism

Perhaps we should view the Russian excursion into Ukraine in a similar way. The Russian invasion of that country is not about protecting Christian values or getting rid of Nazis, but rather the last kicks of the dying horse of Russian imperialism.

Of course, neither Georgia nor Ukraine is perfect. Ukraine in particular is deeply corrupt, and rights of minorities such as gay people are not respected as they should be. However, both countries have the right to resist Russian domination and should be supported in this.

Finally, we must also remember that there are real people living in the countries we see on the evening news or read about on news sites. There are people with lives, hopes, and ambitions behind each of the statistics, whether they are in Kiev, Tbilisi, an Israeli kibbutz, or Gaza.

[Images: Marius Roodt]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend