This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

December 8th, 1974 – A plebiscite results in the abolition of the monarchy in Greece

Map of Greece, drawn in 1791 by William Faden

The modern nation of Greece was born of a violent rebellion against the Ottoman empire in 1821. The initial Greek government of this new nation was little more than a collection of local regional councils established by the rebels.

While these governments officially established a central government in 1822, it had little control until a few years later.

The initial Greek government, today known as the First Hellenic Republic, was deeply unstable and went unrecognised by other nations. The subsequent Ottoman victories over the Greek rebels almost extinguished the rebellion by 1827.

The Siege of the Acropolis [By Georg Perlberg (1807-1884) [http://www.greeknewsagenda.gr/index.php/interviews/rethinking-greece/6911-heraclides, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=80577667]

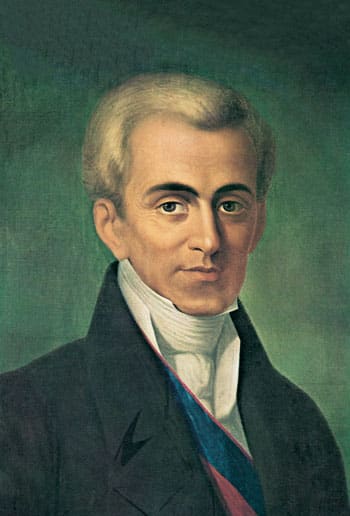

However, the remaining rebels at this time managed to codify their state and selected Count Ioannis Kapodistrias as the first “Governor of Greece” establishing the Hellenic State. He would bring some stability to the Greek government until his assassination in 1831.

Count Ioannis Kapodistrias

The Greek rebellion had won over many in the European Great Powers and French, Russian and British support for the rebels swung the balance of forces decisively against the Ottomans allowing a Greek victory by the year 1829.

Greece was recognised as an independent state in 1830. However, the great powers decided that they would shape the final Greek political settlement, without Greek involvement, as a means of preserving the balance of power in Europe. At the London Conference in 1832, the British, Russians and French decided that Greece would be a monarchy and that it would have a prince of Bavaria as its king, so long as Bavaria and Greece would never become joined in union.

The prince selected to rule Greece was called Otto and he was the second son of Crown Prince Ludwig of Bavaria. Otto was only 17 at the time he was elevated to the throne of Greece.

Prince Otto of Bavaria, King of Greece, after Joseph Stieler (1781–1858)

For the first three years of his reign, Otto was controlled by a Regency Council of advisors. The new king’s government was soon unpopular with the Greek populace, as the foreign Bavarian ministers taxed the population more heavily than did the Ottomans to ensure the many loans Greece took during its initial establishment were paid off. The Greek population had a long history of dodging Ottoman tax collection, and this continued into the new regime, resulting in inefficient tax collection.

Otto would become essentially an absolute monarch after taking control from the Regency Council in 1835.

His reign would last only eight years, however, as he proved ineffective at managing the country. In 1843 a revolution broke out and Otto was forced to fire his Bavarian ministers, accept a new constitution and allow for universal suffrage in Greece.

Otto would remain deeply unpopular, and resisted the new constitution whenever he could. He would be finally overthrown in 1862 by another successful revolution.

The Greek government nevertheless decided it would remain a monarchy and held a public referendum to see who the public wanted as the new king.

Some 95% of the votes were in favour of second son of Queen Victoria, Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. The previous king, Otto, received only one vote of the 240 000 cast.

The Great Powers of France, Britain and Russia were concerned that should a member of one of their royal families take the crown this would upset the balance of power, and so pressured Alfred not to take the throne.

The next 17 options on the ballot either refused the offer of the Greek throne or were rejected by the government. Finally, number 18, Prince William of Denmark, accepted the throne. Prince William had received only six votes. Prince William was, however. acceptable to the great powers and so he assumed the crown of Greece. Taking a new name, he became George I of Greece.

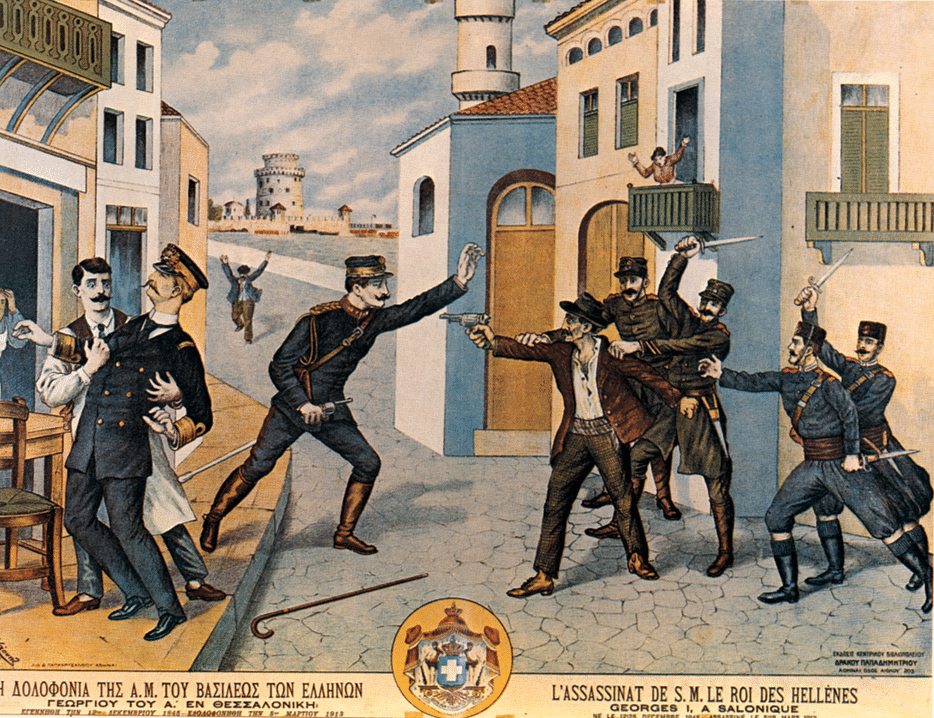

He would serve as Greece’s constitutional monarch from 1863 until his death by assassination in 1913.

Assassination of George I by Alexandros Schinas as depicted in a contemporary lithograph

During his reign, Greece expanded significantly at the expense of the Ottoman eEmpire, bringing many more Greeks under the ruler of the Greek state.

What happened next is described in this edition of This Week in History.

Greece’s monarchy was abolished for the first time in 1924, with King George II being deposed and Greece becoming a republic for a time. However, after a coup by the military in 1935, a rigged referendum was held and the monarchy was restored, with George II returning to the throne.

George II

George would remain the Greek head of state through the Second World War, in part in exile after the Germans and Italians captured Greece. During his exile, the communist partisans became the largest resistance force against the occupiers and, at the end of the war, expected to be installed as the new government of Greece.

To their horror, they would learn that Stalin had conceded Greece to the Western Powers in the Yalta conference, and so control over Greece would be returned to the Greek government in exile and George II.

This led to a civil war, which the communists would eventually lose in 1949 as the government was supported by British troops.

A member of the Security Battalions with a man executed for aiding the Resistance in the civil war [By Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-179-1552-13 / Drehsen / CC-BY-SA 3.0, CC BY-SA 3.0 de, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5476364]

A new referendum was held in 1946, as part of government efforts to solidify their legitimacy and 68.41% of Greek voters backed remaining a monarchy. There is believed to have been significant vote rigging in this election, but it is unknown if this was enough to change the result. Communist-controlled areas were blocked from voting as the communists did not believe the referendum to be legitimate and so prevented voting in it.

Greece remained a monarchy for decades after, remaining politically unstable, but experiencing major changes.

In 1967 a military coup overthrew the democratic government and ruled Greece. After an economic downturn in 1970s, however, the military government began to become unpopular, and so attempted to reform in a more democratic direction. After a coup attempt by the navy against the military government, which the government suspected of being assisted by the Greek king Constantine II, a rigged referendum was held which abolished the monarchy.

After the Turkish invasion of Cyprus (you can read more about it in this edition of This Week in History), the Greek military government collapsed.

The newly restored democratic government decided to hold a free referendum to determine if Greece would stay a republic or return to being a monarchy. Constantine II was banned from returning to Greece to campaign, but was allowed to take part in televised addresses and involve himself in debates.

Constantine II

Officially, none of the political parties took part in the campaign, though the left tended to be republican and the right pro-monarchy. Finally, the vote was held on 8 December 1974, and 69.18% of voters voted for Greece to remain a republic.

Crete voted most strongly for the republic, while the southern Peloponnese voted most strongly for the monarchy. This time, the monarchy was abolished for good.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend