This is not the time of year to be writing about current politics, so I shall not do so. It is the time of year for inspirational messages. But I shall not do that either, because I am not very good at inspirational messages and I suspect most people have had more than enough of them anyway.

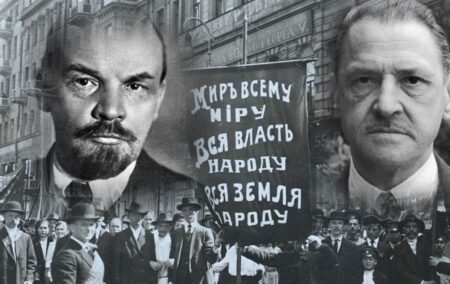

Instead I shall write about a little historical oddity, a near encounter between Vladimir Lenin and William Somerset Maugham in Petrograd, the capital of Russia, in 1917. You could not have had two more different men, although they arrived in Petrograd over exactly the same concern and on exactly opposite missions about it. They arrived in Petrograd, then capital of Russia, by rail from opposite directions, Lenin from the west, Maugham from the east.

(The former capital of Russia, at the coast, was first called St Petersburg, then Petrograd in 1914, because St Petersburg sounded too German and Russia was at war with Germany, Leningrad in 1924, and back to St Petersburg in 1991.)

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov was born in Russia in 1870. His whole life was dedicated to revolution. Karl Marx was his god. He took the name Lenin as an alias, to escape the attention of the authorities. He became a fanatic revolutionary leader, spending all of his days among small groups of bourgeois revolutionaries such as himself, which he always dominated, determined to achieve socialism or communism (the two terms were used interchangeably in those days). When the First World War (the ‘Great War’) broke out in August 1914, he moved from Poland to Switzerland.

In March there was a genuine Russian revolution in Petrograd. Tzar Nicholas II abdicated and a provisional government was formed. It continued the war against Germany. In April the Germans sent Lenin in a ‘sealed train’ from Switzerland through Germany, Sweden and Finland to Petrograd. The Germans plotted that Lenin should lead another revolution and take Russia out of the war, leaving Germany free to fight France and Britain on the western front. It turned out to be one of the most successful plots in history, and nearly led to Germany’s winning the war.

William Somerset Maugham was born Paris in 1874 and then lived in England from 1894. He trained as a medical student in London and qualified as a physician in 1897 but never practised as a doctor. His first book, Liza of Lambeth, a daring study of sexuality among working class girls in the London slums, published in 1897, was a success and he became a professional writer.

Perfect cover

He was too old to fight when war broke out in 1914 but served in Europe in the ambulance service, and no doubt saw terrible things there. Because of his high intelligence, keen powers of observation, linguistic skills, inconspicuous, rather shy personality and perfect cover as an author, he was recruited as a British spy and moved to Switzerland, then a neutral country, and crawling with spies from both sides. Lenin was also in Switzerland at the time.

Based on his experiences there, Maugham wrote a number of wonderful short stories in a book called Ashenden. The fictional narrator in these stories, Ashenden, was obviously Maugham himself, shy, always keeping in the background, cooly observant. By a strange twist of fate, Ashenden made a huge impression on a budding young English writer, Ian Fleming, and he based a wholly fictional and very different British spy on him. The name of his spy was James Bond.

In the introduction to Ashenden, Maugham writes: ‘The work of an agent in the Intelligence Department is on the whole extremely monotonous. A lot of it is uncommonly useless. The material it offers for stories is scrappy and pointless; the author has himself to make it coherent, dramatic and probable.’

In other words Maugham’s spying stories were based not on what happened but on what might have happened if the world were more logical and meaningful than it is. But they are great stories. The Traitor is one of my favourites. Grim and absorbing, it looks at a British traitor who is spying for the Germans, his severe, loving German wife and their darling dog Fritzi. It shocked my girlfriend. My other favourite is Mr Harrington’s Washing. In it Ashenden gets onto a train at Vladivostok to begin the eleven-day journey to Petrograd. He has to share his apartment with Mr Harrington, a prim, frightfully respectable little American businessman.

Ruthlessly boring

Mr Harrington is sweet, innocent and lovable on the one hand, but ruthlessly boring on the other, tormenting Ashenden for hour after hour with long, detailed, edifying stories about himself, his wife, his family, his friends and his church. He comes to a sad end when Lenin’s Bolshevik coup takes place in Petrograd on 24 October (old calendar). In none of these stories does Ashenden show any interest at all in the politics of the war or the politics of the Russian revolution. But Maugham himself really was sent to Petrograd on a political mission.

The British government sent him there, as the German government had sent Lenin. Maugham writes: ‘In 1917 I went to Russia. I was sent to prevent the Bolshevik Revolution and to keep Russia in the war. The reader will know that my efforts did not meet with success.’ Maugham travelled from California to Japan and then to Vladivostok to take the train to Petrograd. He arrived in September. He had with him a huge sum of money to give to Kerensky, then the head of the provisional government, who had just proclaimed Russia a republic, to persuade him to stay in the war against Germany.

Britain desperately needed Russia to maintain the war against Germany on the eastern front. Kerensky was a good weak man. Decent, liberal, well-meaning, a passionate orator, he was also indecisive and ineffectual.

Maugham met him several times and describes him with sympathetic disdain. He writes of him: ‘His emotionalism was a strength in Russia, where the facile expression of feeling has an overwhelming effect, but it was rather disconcerting to English modesty. I could have wished his voice did not tremble so easily. … The final impression I had was of a man exhausted. He seemed broken by the burden of power. … It was easy to understand that he could not bring himself to act. He was more afraid of doing the wrong thing than anxious to do the right one, and so he did nothing until he was forced into action by others.’ The differences between Kerensky and Lenin could not have been starker. No wonder Lenin found it so easy to push him aside.

The one and only thing

Maugham’s mission was always doomed because the one and only thing that could have kept Kerensky in power and kept Lenin out of power was to take Russia out of the war. The war was crippling the country and causing immense hardship and hunger among the people and, importantly, the soldiers. Kerensky’s liberal reforms had broken down discipline in the army. Morale was rock bottom. Millions of soldiers had deserted. But Kerensky insisted on another expensive attack on the German army. It was a disaster. The provisional government collapsed into confusion and ruin. Power was available to anyone who would seize it. Lenin did so on 24 October.

Lenin and Maugham never met. What would have happened if they had? Nothing. Neither had the slightest chance of influencing the other. Neither would have been the slightest interested in the other. Maugham would have summed up Lenin at a glance and found him of no interest whatsoever. Lenin would not have understood Maugham at all and would have had no interest in understanding him. Maugham, like so many of the characters in his novels and short stories, was a complicated man, full of contradictions, often tormented by desires he knew to be unworthy, as he describes so painfully in Of Human Bondage.

His homosexuality, unlawful in that bigoted age, would have added to his deep insights into male and female sexuality, his understanding of the torture of unrequited love, and the pain of his own being, despite his enormous success. He often said, ‘No man is all of a piece’, by which he meant that we all consist of many contradictory personalities. But I think Lenin was all of a piece. He only had one personality. He was the closest thing to a one-dimensional man there has ever been.

Deep and sympathetic understanding

From first consciousness, Lenin – unlike Hitler – knew exactly his destiny: to lead a Marxist revolution in Russia and then the world. His theories, like Marx’s, were mainly nonsense. He had little understanding of history or modern economics or the working classes he prattled on about – unlike Maugham, who had a very deep and sympathetic understanding of the working classes. Events took him by surprise. But like all successful political leaders and like all successful poker players, he was a great opportunist. He never knew when an opportunity or a good hand would come but he recognised it instantly when it did and seized it forcefully.

He had massive willpower and self-confidence. Unlike Hitler, he was no showman and never sought publicity or even popularity. He did not care what people thought of him. He never achieved any popular support and did not mind. He never moved outside a tiny group of middle-class revolutionaries like himself, and always prevailed over them. His sexual and family life seems unimportant and unexceptional. His only drive was for political power. What for? To achieve socialism. What for? To bring about a happy, free and prosperous world. Certainly not. That is for capitalists and counter-revolutionaries.

So what really drove him? The answer seems to be hatred. He seems to have been crueler and more sadistic than Stalin, who succeeded him and killed far more people than him (he had more time to do so). The author Maxim Gorky once said of Lenin, ‘His love looked far ahead, through the mists of hatred’. By ‘love’ I suppose Gorky meant some vague hope for humanity in general but not for people. But that is not love at all. Some people say Lenin’s hatred came from the fact that his brother was hanged for attempting to kill the Tzar, but I doubt Lenin had the humanity to be much moved by the death of his brother. Whatever drove him, the fact was that he was mightily successful at both revolution and hate.

Lenin, almost alone, made all the right moves, difficult, brave moves, at the right time. When the Bolshevik putsch came in October, Trotsky was seen all over the place and Lenin was seen nowhere. But it was Lenin who directed everything behind the scenes and who had decided on the date of the takeover. When negotiations began with Germany to take Russia out of the war, it was Lenin who insisted on accepting German terms at Brest-Litovsk even if it meant Russia’s ceding vast Russian territories to Germany. He was right.

Terror

His ‘revolution’ would have failed without it. He was also right to know that his revolution could only be sustained through terror, by crushing all semblances of democracy or opposition, and by banning all free speech. Socialism could only be achieved by brute force. One of his first moves was to set up the Cheka, which later became the KGB, an instrument of terror and repression, which was soon executing far more people than the Tzars ever did. Lenin knew exactly how to seize power and keep it but he had not a clue how to run an economy or how to feed the people. So the economy collapsed under his socialism and people starved and died.

Lenin never produced anything but tyranny, famine and the brutal exploitation of the working classes and peasants. Naturally this made him a big hero among the privileged elites in rich Western countries, in the universities and editorial rooms. He remains so today. The ANC elite and the EFF elite just love him, and want to enact his policies in South Africa.

By contrast, Somerset Maugham had a deep interest in people and sought to understand and describe their passions and doubts. I do not think he particularly loved the human race but wished it well and wanted it to be happy, and in his wonderful stories made it interesting and entertaining. Unlike Lenin, Maugham had much experience of the real world. He had dissected dead bodies, he had worked in the slums of London and on the battlegrounds of Europe at war, and he understood the different classes and the different nations. But he almost never wrote about his harrowing experiences with life and death or ever showed the slightest interest in the politics of his age or in the tremendous historical events surging around him.

He just wrote about personal love, betrayal, violence, snobbery, obsessions in love and art, and hidden passions among ordinary people. He once wrote a telling essay on Jane Austen, whom he much admired. He admired her cleverness and wit, her well-structured plots and her cool, sympathetic detachment. He doubted she had ever loved and even said she was incapable of love, because she was incapable of surrender.

Vulnerable to love

He was probably right and probably envious of her because of it, since he was so vulnerable to love himself, and often painfully unsuccessful. He also commented that though Jane Austen lived among great and terrible events of her time, including the Napoleonic wars, in which her own brother took part as a rear-admiral in the Royal Navy, she never wrote about them. She confined her writings to social gossip among the landed gentry. Maugham said this was because this is what interested her and was moreover of enduring interest down the ages, whereas historical events lost popular interest over time.

I do not think this is true, but it might explain why he himself never wrote about historical events. More likely though, he like her was more interested in gossip and local human drama. Judging by the magazine racks and newspaper sales, so are most ordinary people today.

I wonder if Vladimir Putin has read Mr Harrington’s Washing.

[Image: Composite of material drawn from https://picryl.com/media/political-demonstration-at-petrograd-18th-june-1917; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._Somerset_Maugham#/media/File:Maugham_retouched.jpg, and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vladimir_Lenin#/media/File:Lenin_in_1920_(cropped).jpg]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend