This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

29th January 1918 – Ukrainian–Soviet War: The Bolshevik Red Army, on its way to besiege Kyiv, is met by a small group of military students at the Battle of Kruty

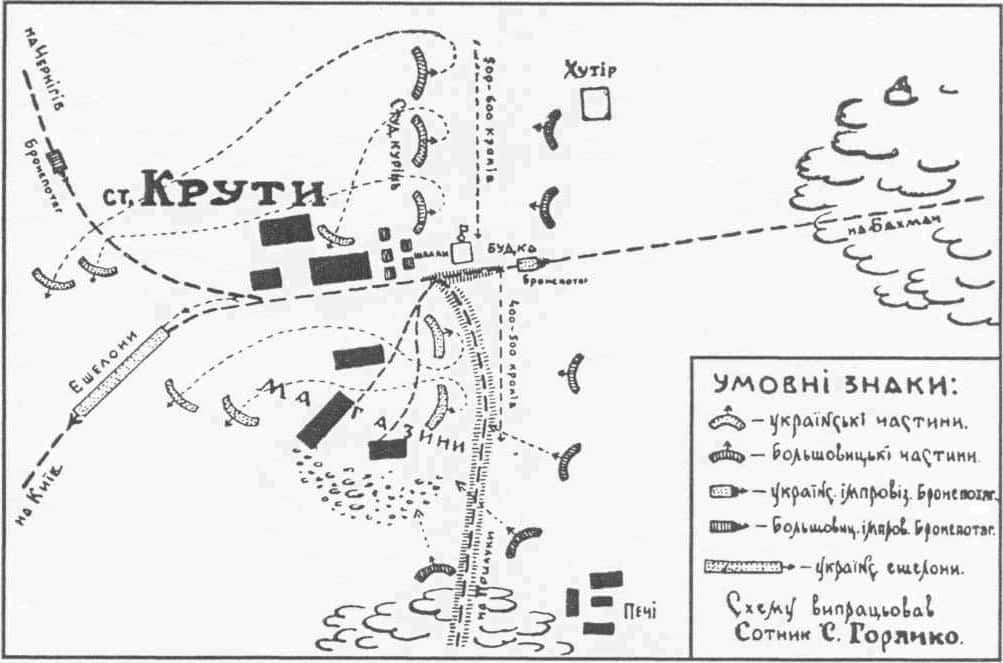

Map of the Battle of Kruty

The Russian Revolution of February 1917 overthrew the Tsar and established the Russian Republic. However, it found itself in a precarious position, as Russia was still at war with Germany (in the First World War), the government was deeply divided between various ideological groups, it was unstable and many of the long-suppressed minority groups across the former empire were demanding greater autonomy.

The new Provisional Government was ultimately unable to stabilise itself and in November 1917 (October in the Russian calendar at the time) it was overthrown in an armed coup by the Bolsheviks.

After the capture of the Winter Palace, Petrograd, 26 October 1917

In March 1917, a central government of Ukraine was elected and declared ‘Ukrainian autonomy within Russia’. This was later recognised by the Provisional Government in Russia. When the Bolshevik coup took place, the new Ukrainian government denounced the coup and proclaimed the Ukrainian People’s Republic, and would later declare independence from Russia, on 22 January 1918.

In the run-up to the peace negotiations between Russia and the Central Powers, held at Brest-Litvosk, Ukraine sent a delegation asking for recognition from the international community as an independent nation and by 12 January 1918 the Central Powers had recognised the Ukrainians as a separate party from the Russians at the negotiations.

However, as the Bolsheviks carried out their coup in Petrograd and Moscow, they also launched an uprising in Kyiv. This was quickly crushed, and the city came back under the control of Ukrainian troops.

The Bolsheviks would quickly establish their own puppet Ukrainian government in December of 1917, which was called the Ukrainian People’s Republic of Soviets and was based in Kharkiv, while the anti-Bolshevik government was based in Kyiv.

Participants of the January Uprising in Kyiv

Soon after the establishment of the Soviet-controlled Ukrainian government, Bolshevik troops entered into Ukraine to put down the Ukrainian People’s Republic. The Bolsheviks feared that Ukraine would be recognised as an independent nation by the Central Powers at the Brest-Litovsk negotiations, and would then become harder to conquer and might be able to gather international allies.

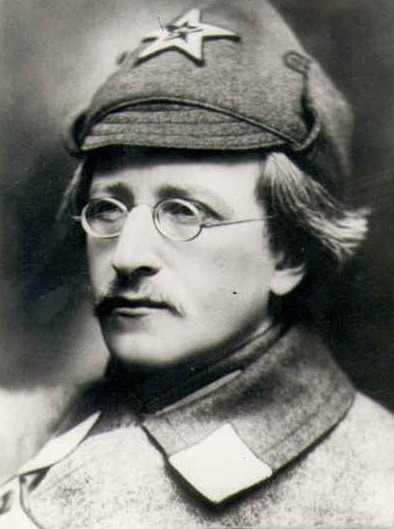

Vladimir Alexandrovich Antonov-Ovseenko, who led the Soviet army that marched on Kyiv

By the end of January, a Soviet army was marching on Kyiv from the northeast and had defeated many Ukrainian troops defending their territory. The Soviets seemed sure to capture the Kyiv. The Soviet force numbered around 5 000 and were opposed on their march to Kyiv by a small Ukrainian garrison at Bakhmach, which numbered around 500 troops, 400 of whom were recently armed students from the Khmelnytsky Cadet School. The other 100 were Cossack troops of the Nizhyn Free Cossacks.

Soldiers of the Ukrainian National Resistance Army in front of Saint Michael’s golden-domed monastery in Kyiv

A fierce battle would ensue at the Kruty train station that would come to be known by many in Ukraine as the ‘Ukrainian Thermopylae’. Led by experienced officers who had fought against the Germans and Austrians in the First World War, the Ukrainian forces would initially halt the Russian advance, delaying it by several days. Eventually, however, they would be defeated when another Soviet force flanked them on 29 January.

A Soviet-supported uprising began in Kyiv at the same time and, soon after, the Ukrainian government had to abandon the city. The delay of the Soviets’ advance had allowed the Ukrainians to achieve international recognition, and soon the Ukrainian army was joined by thousands of German and Austro-Hungarian troops. However, the new allies would fall out with the Ukrainian government and overthrow them, replacing them with a pro-German puppet government, known as the Hetman government in April of 1918.

On 12 June the Soviets signed a ceasefire with the Ukrainian government, agreeing that a treaty determining the new border between Ukraine and Russia would be signed later. These negotiations would collapse when the Germans lost the First World War, and the pro-German Ukrainian government was overthrown.

On 7 January 1919, the Soviets returned, invading Ukraine again. The Soviet armies were initially successful, capturing Kharkiv and Kyiv, but were driven back by a Ukrainian counter-attack, which seemed on the verge of regaining Kyiv. However, the Ukrainian army was hobbled by major disease outbreaks.

As Ukraine fought for independence against the Soviets, it also faced clashes with the newly created Polish Republic (also born from the corpse of the collapsing Russian Empire), which claimed some of the western territories Ukraine had laid claim to, as these had a significant Polish population. In early 1920 this came to an end when the Poles and Ukrainians signed a treaty and became allies. A joint Polish and Ukrainian offensive recaptured Kyiv in the first half of 1920.

Edward Śmigły-Rydz saluting the Polish Army in the parade celebrating recent victory in the 1920 offensive, Kyiv, 8 May 1920

The allies’ effort would stall, though, and the Bolsheviks would return to the offensive, pushing Poland out of Ukraine and nearly capturing Warsaw. They were, however, defeated at the legendary ‘Battle of Warsaw’ (which you can read about in this edition of This Week in History).

The Poles would successfully retain the territories they wanted at the end of the Polish Soviet War, but there was no appetite in an exhausted and devastated Poland to restore the Ukrainian government ,and so Ukraine fell under Soviet control, becoming a constituent Republic of the Soviet Union until the collapse of the USSR in 1991. Partisan warfare would continue against the Soviets for many years and would eventually be repressed by Stalin.

The Battle of Kruty, would go down in Ukrainian national history as an almost mythical event, and its anniversary is celebrated in Ukraine every year.

A hryvnia coin commemorating the Battle of Kruty

Former Ukrainian Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko said of the battle:

‘Young people, like Spartan soldiers, died for the sake of their motherland in a struggle against foreign aggressors, and it was an example of their sacrifice and selfless love for their native land. Every anniversary of the Heroes of Kruty is not only a day to honour those people who loved our motherland more than their lives. This is also another reminder to our contemporary politicians regarding their responsibility for the fate of their country and people.’

Former President of Ukraine Viktor Yuschenko would say:

‘Near Kruty the Kyiv military cadets and students became the forerunners of the Ukrainian political nation. Having different ethnic roots, they as one fought for our Ukrainian State. As the founding of the Ukrainian People’s Republic became the base of the Ukrainian statehood, so the heroism of the Kruty’s warriors became the beginning and the symbol of liberating struggles of Ukrainians for the liberty in the past 20th century.’

The battle is referenced in this Ukrainian music video from last year:

In the initial stages of the Russian invasion in February 2022, Russian soldiers captured the monument to the Battle of Kruty and took selfies with it behind them, and shot at it.

Battle of Kruty monument [Dctrzl, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=65940302]

They were later driven from the area by Ukrainian troops on 1 March 2022 after a short but fierce battle. Media reports citing local residents claim that 200 Russian troops were killed in the 2022 Battle of Kruty.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend