At the mercy of several bureaucracies, tourism has been bruised and battered by ANC rule.

In what appears to be a slapstick attempt to shoot itself in the foot, the Department of Home Affairs has declared that tourists presently in the country on a 90-day visa, but who cannot get their visas extended because of backlogs in processing applications, must leave the country by the end of February.

Leaving aside the unacceptability of not being able to process visa extension applications, surely the obvious solution would be to grant visitors a six-month visa from the start, or to deem visas as having been extended if the visa-holder can show that they have applied for an extension but haven’t received a reply yet.

The last time I obtained a US tourist visa, it was valid for ten years, allowing me to visit the US multiple times for up to six months per visit. If South Africa wants tourism to thrive, why can’t it issue similar visas?

Living in a small coastal tourist town, I am acutely aware of the importance of so-called ‘swallows’ for the South African tourism industry. A whole economy of hotels, guesthouses, restaurants and tourist attractions relies on seasonal visitors who flee the northern hemisphere winter to enjoy South Africa’s summer months. They all bring dollars or pounds or euros, which keep thousands of people employed.

Booting them out is by far the most stupid solution that Home Affairs could have found to deal with its self-inflicted crisis.

Arrivals

It is far from the only poor decision Home Affairs has made, however, and Home Affairs is far from the only government department that routinely puts sticks in the spokes of the tourism industry.

It might be the most battered industry sector in the country, in fact.

According to the government’s official tourism website, South African tourism is enjoying ‘rising momentum’.

That would be nice, but it is highly misleading.

‘The total number of arrivals reached 8.48 million, marking a significant 48.9% increase from the figures in 2022,’ its infographic proclaims. Of this, 6.4 million is tourism from Africa.

What they don’t tell you is that this figure is still 17.1% below pre-pandemic levels in 2019, and South Africa is recovering more slowly than its international rivals. If you take Africa out of the equation, 2019 arrivals were at 2.6 million, compared with 2.06 million in 2023, a decline of 20.8%.

Bragging about growth when it comes off the back of an extended government-imposed ban on tourism is hardly honest.

Visas

Visas for swallows aren’t the only problems with Home Affairs. The entire visa system is broken, and designed to keep people out, rather than in.

In 2015, the debacle about requiring unabridged birth certificates from parents travelling with children, and requiring single parents to obtain written permission from the other parent to allow children to travel, was a solution to a problem nobody had.

Child trafficking in South Africa is not a major problem, and what does occur happens within the country or across land borders, and not at airports.

By the time this heavy-handed policy was reversed, South Africa had lost 5% of its tourism arrivals, for which the Department of Home Affairs has never accepted responsibility.

China and India

An even bigger problem for South African tourism is the ineffective visa system for two of the world’s largest outbound tourism markets, namely China and India.

Travellers from the US and Europe do not need a visa to visit South Africa. As a result, these two markets account for 82.2% of all arrivals from outside of Africa.

In 2017, President Jacob Zuma decided he liked Russia so much that he also lifted visa requirements for Russian tourists. The impact was felt immediately. By 2019, arrivals from Russia had doubled, from 8 307 in 2016 to 16 276 in 2019.

Yet Home Affairs still requires visas for Chinese and Indian visitors. As one industry contact put it: ‘Are Russians just nicer people, and more trustworthy, than Indians or Chinese?’

It claims to have an e-visa system in place, but it caters only for individual travellers, and takes payment only via Visa and Mastercard.

These payment networks have only just entered the Chinese market, and very few Chinese travellers use them. The system also doesn’t cater for group travel, which accounts for by far the majority of Chinese outbound travel arrangements.

Whether for e-visas or in-person applications, South Africa requires that travellers apply in English, which is just as absurd as China expecting South Africans to apply for visas in Mandarin.

Worse, it employs so few visa officers in these countries that there are large delays in visa applications, and there is no scope at all for growth in these markets.

The upshot is that both Chinese and Indian travel to South Africa peaked in 2013, with 151 000 arrivals from China, and 112 000 arrivals from India. By 2019 (which is the last year uninfluenced by the pandemic) these numbers had declined to a measly 93 000 from China and a mere 96 000 from India.

They account for only 6% of South Africa’s arrivals from outside Africa, despite being by far the largest sources of global tourism.

Contrast Australia

By contrast, Australia has had a massive whole-of-government drive to improve its tourism offerings and remove bureaucratic obstacles to tourism, especially from China and India.

While South African numbers remained in the doldrums, Australia rapidly increased the arrivals it accepted from China and India. Chinese visitors in 2013 stood at 700 000, and by 2019 had grown to 1.4 million. For India, arrivals grew from 177 000 to 399 000.

It can be done. But Australia has enough staff to process visas, makes the process as easy, accessible and painless as possible, and importantly, allows visitors to apply in their native languages.

BRICS benefits?

South Africa should strongly consider extending visa-free travel, which it has extended to Russia, to the other members of BRICS.

If not, there are other ways to shortcut visa-processing times: if a traveller already has a US visa, a Shengen visa, or an Australian visa, then by what logic would South African Home Affairs have to determine whether they are worthy of a South African visa? Just issue such travellers visas automatically.

Kenya has, as of 1 January 2024, abolished visa requirements for all foreign travellers, instead implementing an electronic travel authorisation system for all travellers who are not exempted from the requirement to have an authorisation. This authorisation can be acquired for $90 upon arrival in Kenya.

The costs of visa delays

The tourism industry has been appealing to government for well over a decade to improve its visa-issuing system.

Ten years ago, the Southern African Tourism Services Association warned that tourism growth from India was slowing. It noted that the four visa officials who were supposed to operate in India would have to issue 1.43 visas every minute of the day to keep up with demand, but that of the four, three had left, leaving the entirety of India to a single visa official.

This led to serious delays in issuing visas, even then. As a result, Indian outbound tour operators were directing travellers away from South Africa to other destinations, and South African inbound operators had to deal with large numbers of cancellations, costing them millions.

Tour vehicle permits

Two years ago, I wrote about the catastrophe that is the National Public Transport Regulator (NPTR), where a bunch of pencil-pushers focused on the taxi industry are employed to issue vehicle operator permits for the tour vehicles of accredited tour operators.

By law, the regulator is required to issue new vehicle operator permits in 60 days, and renewals in 14 days. (This has been changed, since the original one-day turnaround proved to be entirely unachievable.)

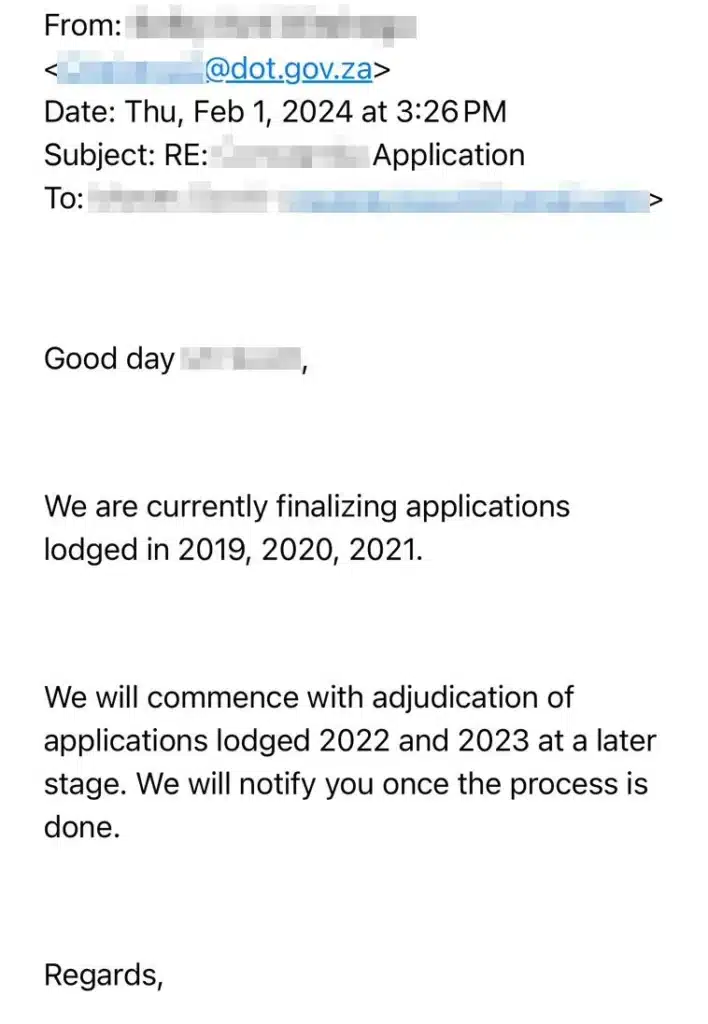

Here is an email from someone who enquired about the progress of their vehicle operating permit application:

A contact in the industry tells me it took him a year just to obtain renewals on his tour vehicles.

This is, of course, outrageous, and entirely untenable. People are trying to run a business. Having vehicles stand idle for years while some government bureaucrat finds his rubber stamp is a millstone around a tour operator’s neck.

Vehicles are capital investments that need to earn revenue to pay for themselves. Without that revenue, where do the loan repayments and insurance instalments come from?

This hits especially hard for new (and often black) entrants to the market, who scrape together enough capital to buy a vehicle, and want to begin offering tour services, but are blocked by the NPTR for years while their permit applications are processed.

Operators who use vehicles without the requisite permits risk being bullied by roadside traffic police, or having their insurance claims denied.

Making it harder

Instead of having made the process easier in the years since it was first raised, the NPTR, which falls under the Department of Transport, has made it even harder.

At first, they introduced tour operator accreditation, which was supposed to make it easier to obtain vehicle operator permits. Accredited operators wouldn’t have to jump through as many hoops as new entrants to the market.

Instead, they have changed the regulations – in conflict with the National Land Transport Act – to make vehicle operator permits expire not after the legislated seven years, but when a tour operator’s five-year accreditation expires.

That means that if your accreditation is up for renewal in six months, your vehicle operating permit, or permit renewal, will only have a six-month validity, after which you need to restart the application process, submit all the documents again, and pay the required fees again.

Many operators are simply not bothering to get new tour vehicles on the road in the last year or two of their accreditation, which deters investment in and capitalisation of tourism operators.

This complicated licencing procedure, which obviously doesn’t achieve anything other than keeping brand new tour vehicles off the road, is doubly galling when one realises that there is actually no need for operating licences for tour vehicles at all.

If a person or company is an accredited tour operator, its driver has a professional driver’s permit entitling them to carry passengers, and its vehicle is duly licenced and roadworthy, there is no reason why they shouldn’t be permitted to transport tourists.

But no, the bureaucrats will bureaucrat, at the massive expense of the tourism industry.

Endless list

The list of body blows to the tourism industry is long. Instead of embracing new technology and more efficient business models, vested interests have convinced government departments to clamp down on industries such as home sharing and ride sharing.

This makes accommodation more expensive and less available, and makes public transport less convenient for tourists. This directly and indirectly harms tourism businesses across the country.

Regulations should make it easier to do business, not harder.

Before South African Airways collapsed, it made itself guilty of unfair competition. The beneficiary of numerous large bailouts, and preferential access to facilities at the state-owned Airports Company South Africa, placed every competing airline, international and domestic, at a disadvantage.

Then, SAA collapsed, which sharply reduced air access to South Africa. Either way, the tourism industry suffered.

The out-of-control crime rate has also touched the tourism industry, on several occasions. The risk of gaining a reputation as an unsafe destination is so terrifying to the tourism industry that it would rather not talk about it at all.

Obdurate bureaucracy

All of this is attributable to intransigent bureaucrats, who are anti-business, and to whom competitiveness doesn’t mean a thing. They get their salaries no matter what.

Nobody has the willingness to overhaul the systems, and to do what the tourism industry clearly tells government it needs. Workable solutions proposed by the industry are simply ignored.

If you thought there was anyone in government who cared, you’d be wrong. President Cyril Ramaphosa himself sort of shrugged when interviewed by the media last Thursday, saying that government is doing what it can but some civil servants are stalling.

‘[S]ometimes it is challenging because you find civil servants are trapped in the old ways of doing things,’ he said.

Mr President, you are their boss. If they refuse to comply with instructions, then shout at them. If they still refuse, discipline them. And if they still refuse, fire them.

You can’t have bureaucrats running free, doing whatever they please, damaging the private sector and undermining the interests of South Africa.

If that is the status of the civil service, and you and your cabinet, Mr President, are unable to enforce your authority upon them, then you have no business pretending that you’re running the country.

All these problems can be fixed, easily, within months. The tourism industry has been begging for over a decade to get them fixed. Yet the government simply isn’t interested, and blames disobedient civil servants.

The moribund bureaucrats are running the show, and that, frankly, is a gross dereliction of duty on the part of the government. What use have we for such a powerless government?

[Image: Public domain photo. Composite created by Ivo Vegter]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend