Finance Minister Godongwana’s budget averted any meaningful funding heading the way of National Health Insurance (NHI). Although he categorically rejected NHI last year as a fiscally feasible policy, 2024 is an election year, so we must assume that he was obliged to toe the ANC party line when he stated in the budget speech that government is fully committed to NHI.

After all, President Ramaphosa taunted in the SONA that he was searching for his pen to sign it into law.

Nonetheless, outside of contradictions and fiscal feasibility, the one propaganda success that the ANC can certainly claim is the NHI position that current public health resources are inadequate to deliver better healthcare. Considering the poor quality and frequent disasters befalling the public department, it is not unreasonable for an observer to agree.

But this is standard fodder from socialists. Just give us plenty more of other people’s money – additional NHI tax estimates range from R200bn to R800bn annually – and we will produce amazing outcomes.

The ability to obscure the truth through misconceptions is often powerful.

Public Health Resource Boom

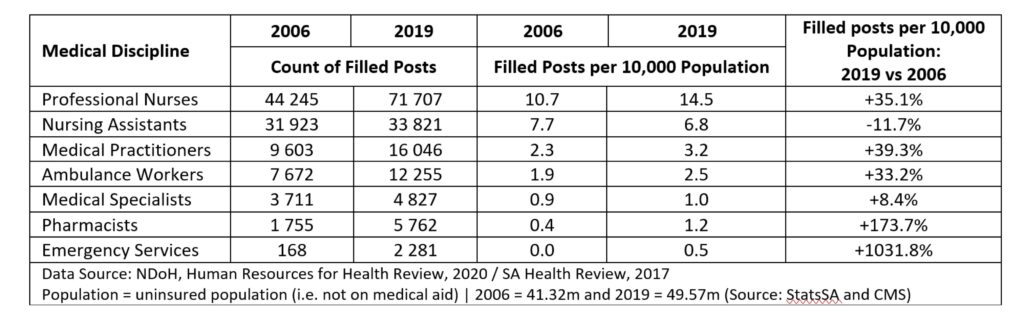

The table below corrects one particular misconception – it shows that the number of medical personnel employed by the state increased substantially during the last thirteen years. Even with the growing population, the ratios of medical personnel per 10,000 population have risen significantly.

Medical personnel in 25 out of 28 medical disciplines in the public sector experienced improvements in their ratios per 10,000 population between 2006 and 2019.

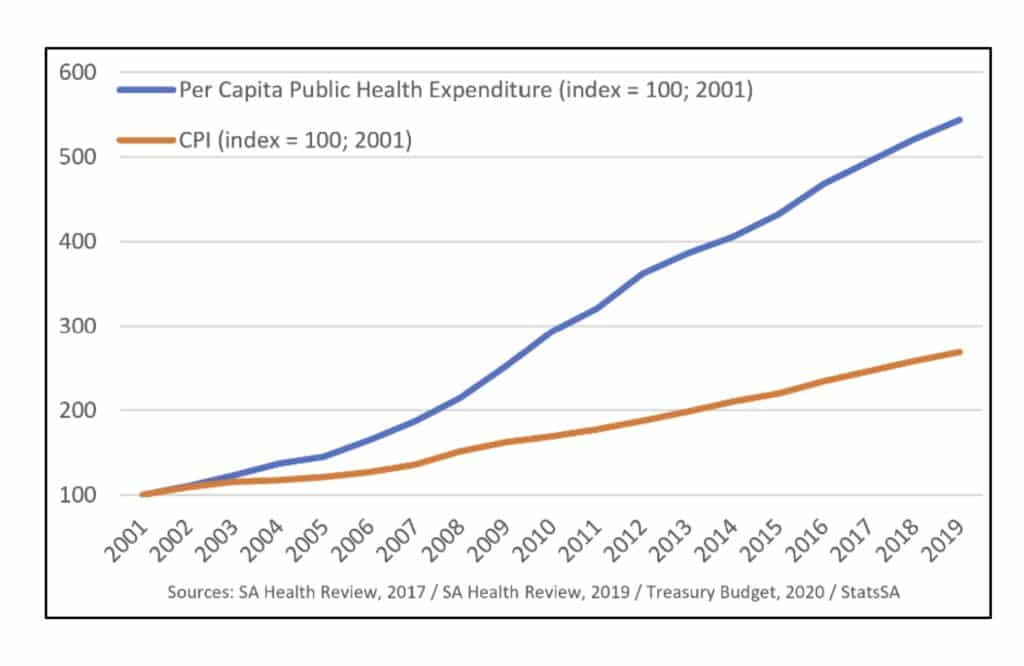

This was possible through annual increases in public health expenditure considerably above CPI and population growth over many years. Considering that per capita measurements account for population growth, the graph below indicates how ‘per capita’ public health expenditure (blue line) grew to more than double the rate of CPI (orange line) from 2001 to 2019.

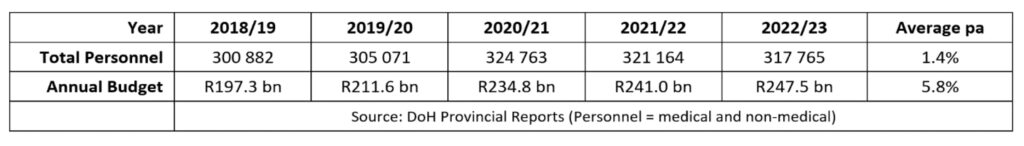

Growth in personnel and budgets for the provincial health departments in more recent years:

Given that population growth rate is around 1.4% per annum, the same average increase in personnel above means the ratio of health sector personnel to population has been maintained. The total provincial budget over the same period above increased on average by 5.8% per annum, lower than in previous years, but still in excess of the CPI.

Surely it behoves any parliamentarian faced with these indisputable and publicly available facts to question why outcomes in the public sector have not significantly improved over the past 20 years? And to question whether demanding substantially more funding via NHI will realistically improve outcomes?

This would, of course, require inquisitorial ANC parliamentarians rather than complicit and ideologically brainwashed ones to pose such questions. It is obvious that during the NHI policy process, such questions have only emanated from the opposition benches, the private health sector, civil society and business lobby groups.

Nonetheless there are a few apparent answers.

Real Problems

The breakdown of governance and the incapacity of deployed managers have routinely been highlighted by the Office of Health Standards Compliance as the weakest outcomes across all audited metrics in the public health department. Even where competent managers exist, their attempts to intervene with non-performing staff are often met with violent threats and intimidation from unions, undermining any possible performance correction.

When assessing the astronomical sums pilfered out of public health budgets in the department’s rampant corruption, it is simple to determine how the diversion of resources – meant to purchase medicines and materials or to maintain equipment and facilities or to fill empty posts – severely hampers service delivery.

Another form of fraud is abuse of the dual practice policy. Public sector personnel are permitted to operate a private sector practice (doctors) or to contract with private sector providers (nurses), as long as this is not done on state time. However, dysfunctional management has enabled endemic abuse of this practice – called moonlighting. Tales abound of public sector doctors spending barely a few hours a week in their fully paid public sector post, whilst spending the balance in their private sector practice where they can bill each privately insured patient they consult with. The financial incentive to spend more time in their private sector practice is obvious, yet no noticeable intervention by the health department is taken to avert the widespread problem.

Where to Now?

It is abundantly clear that the resource argument that underpins the NHI policy is a hopeless fallacy.

Governance failures, poor management and endemic corruption are obviously the greatest threats facing the health department and unless dealt with, no amount of additional tax, whether in the form of NHI or otherwise, will improve public health outcomes.

Instead of the NHI Bill, maybe President Ramaphosa should have more interest in searching for a pen to sign into law the Zondo Commission recommendations. That would almost certainly give South Africans a much greater possibility of receiving quality healthcare.

The views expressed in the article are the author’s and not necessarily shared by the members of the Free Market Foundation, the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.