This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

29th February 888 – Odo, Count of Paris, is crowned King of West Francia (France) by Archbishop Walter of Sens at Compiègne

Coronation of King Odo

Charlemagne is sometimes called the ‘grandfather of Europe’, as the mighty Frankish kingdom reached its greatest extent under his rule, and he was crowned as a new Roman emperor by the Pope. It is from the divisions of his empire after his death that we can begin to trace the histories of Germany, France, Italy and the Netherlands.

While Charlemagne was a skilled king and warrior who conquered many lands, this is perhaps giving him too much credit, as he was building on the foundation left by his forebears in the Frankish Kingdom.

Charlemagne offering assistance in repelling raiders to Pope Adrian, near Rome, in 772

The Franks enter the historical stage as one of many Germanic tribes living along the Rhine frontier of the Roman Empire in the 200s AD.

The close proximity to the Romans meant there was significant interaction with them; sometimes the Franks raided Roman territory, sometimes they traded with the Romans, sometimes they fought as soldiers or allies of the Roman army, and as the Roman Empire endured the crises of the 3rd and 4th centuries, many Franks migrated into Roman territory and became settled as allied tribes of Rome.

In the 450s AD, a Frankish warlord known as Childeric I, and his son Clovis I, expanded Frankish territory as the Roman Empire collapsed, conquering much of the northern Roman province of Gaul. They would also expand their territories east across the Rhine to conquer much of modern-day southern Germany.

Their empire came to be known as the Merovingian Empire, named for their family name. meaning ‘sons of Merovech’.

The Franks in many cases simply replaced the Roman armies and allowed their Roman subjects in Gaul to live much as they had, with the Franks forming the new ruling and military class. They began to integrate more thoroughly with their Roman subjects after Clovis I adopted Christianity as the official religion of the Frankish Kingdom in 496 AD.

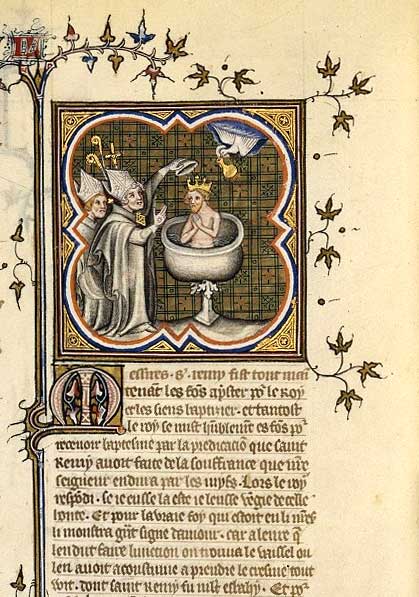

The baptism of Clovis by St Remi at Reims, from the Grandes Chroniques de France (1375-1380)

Eventually the merging of the Roman and Frankish languages and cultures would develop into the early French culture.

Until the 530s, nearly 60 years after the fall of the western half of the Roman Empire, the Frankish kings continued the legal fiction that they were still subjects of the Roman Empire and minted coins with the Eastern Roman Emperor’s face.

The Frankish kingdoms would regularly go through cycles of division and unification, as it was Frankish custom to divide their lands between their sons, and so a powerful king would have his lands split upon his death between a number of sons, who would usually war with each other for supremacy.

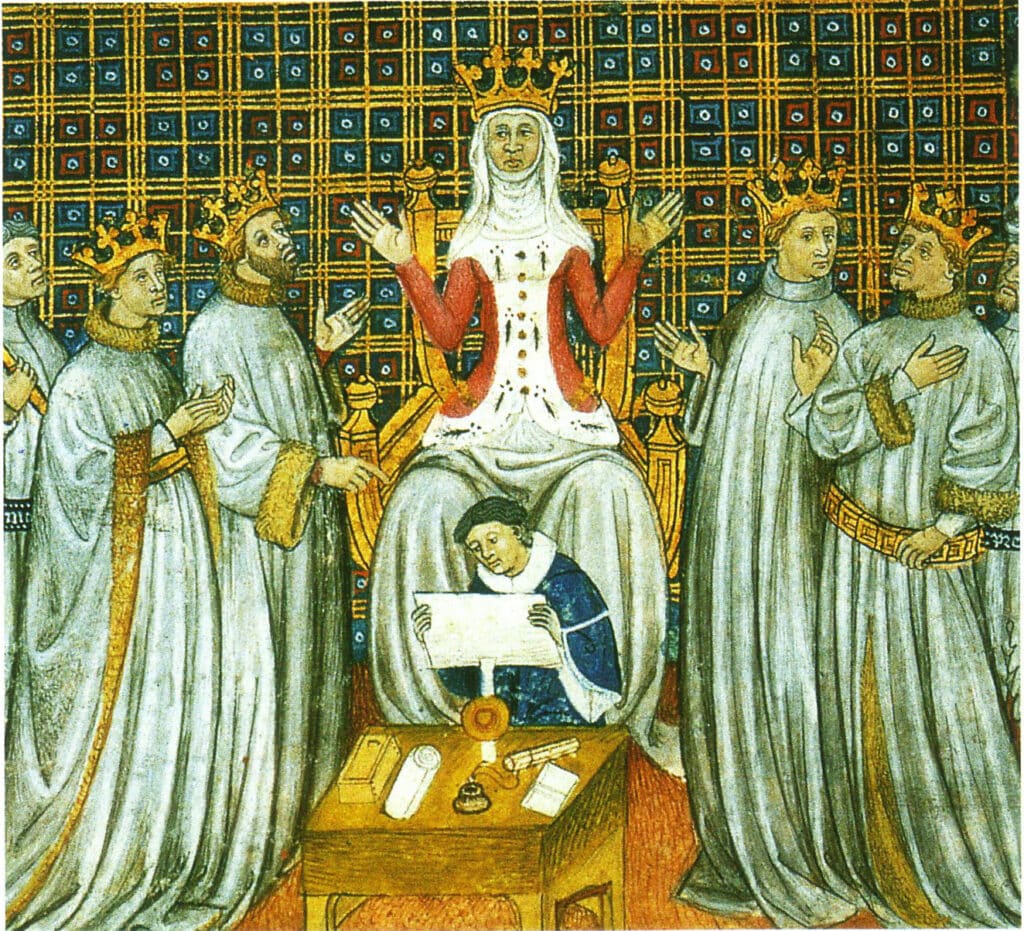

The partition of the Frankish kingdom among the four sons of Clovis, with Clotilde presiding, from the Grandes Chroniques de Saint-Denis (Bibliothèque municipale de Toulouse)

Despite the repeated divisions, the various Frankish kings usually saw themselves as part of one kingdom, even if it had multiple kings. Eventually they would be reunified again under one king. In theory the sons were supposed to work together to support each other, though they rarely did.

The squabbling and civil wars between the various Merovingian kings, saw more concessions granted to the nobility, and, over time, the ‘mayors of the palace’, the most powerful official in the Merovingian court. In 687, these mayors became the true power behind the throne, with the Merovingian kings acting as figureheads.

In 714, a civil war broke out between the Franks, and out of the chaos a man known as Charles Martel became the new Mayor of the Palace and the new de facto ruler of the Franks. His family would become known as the Carolingians or the Karlings, and would become the most important family in Western Europe.

Martel won his most famous battle against the Muslim forces of the Islamic Umayyad Caliphate in 732, the Battle of Tours.

Charles Martel facing Abd Al Rahman Al Ghafiqi at the Battle of Tours, painting by Charles de Steuben

The Umayyad’s had by this point conquered most of Iberia and were now pushing across the Pyrenees into southern France.

The Battle of Tours is considered by some historians as a high-water mark of Islamic expansion and a defeat that was critical in preventing the Islamification of France and western Europe.

Martel’s son, Pepin the Short, would complete the downfall of the Merovingian family by, in 751, deposing the last Merovingian king, who was sent to a monastery, and being elected King of the Franks by the nobility.

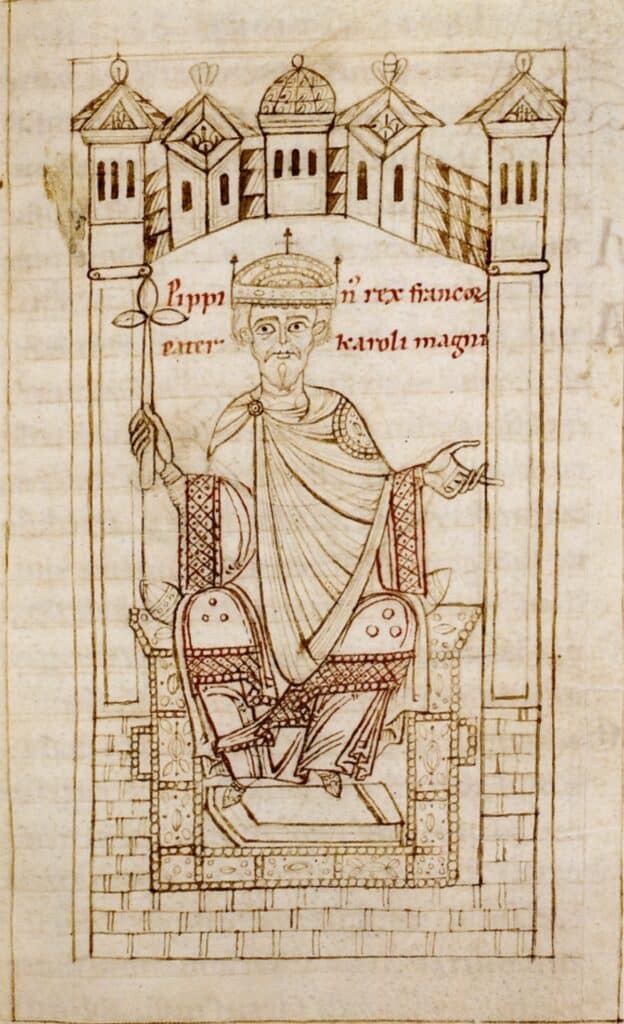

Pepin the Short, depicted in a miniature in the Imperial Chronicle (Anonymi chronica imperatorum), now in the collection of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

This was supported by the Pope, who at the time was fighting against the Lombards in Italy. In 754 Pepin repaid the support by intervening in Italy and defeating the Lombards in battle to secure the Pope’s independence. Pepin would also expand the Frankish Empire into northern Spain, pushing back the Umayyads.

Pepin died in 768 and divided his territory between his two sons, Charles and Carloman. This would not last long as soon Carloman died and Charles became sole ruler of the Franks; he would be better known to history as Charlemagne and you can read more about him in this edition of This Week In History.

Imperial Coronation of Charlemagne, by Friedrich Kaulbach, 1861

When Charlemagne died in 814, instability would plague the Frankish Empire now divided among between his descendants. The empire Charlemagne had built would fracture into three kingdoms: West Francia (modern France and northern Spain), East Francia (western Germany and Bavaria) and Middle Francia (the Netherlands, the French German borderlands, Luxembourg and Italy).

These kingdoms warred endlessly with one another and the Frankish kingdoms became weaker and more divided.

In the mid- to late-800s, Europe was being ravaged by raids from three different but equally terrifying groups: the Magyars (Hungarians) from the east, the Arab pirates from North Africa, and the Vikings from Scandinavia.

While the Carolingian kings fought for the empire of Charlemagne, their people were being slaughtered by raiders who burned and ruined as they went. This saw local peasants, landholders and clergy turn increasingly to the more important nobility for protection from the raids.

In the 850s, the unpopular Carolingian king of West Francia, Charles the Bald, continued to squabble with his relative and rival Louis the German, the King of East Francia and Bavaria.

Charles the Bald

In 866, Charles was fighting a war with the Bretons and Vikings, which he would lose at the battle of Battle of Brissarthe, after which he would recognise the Breton leader as King of Brittany. It was in that battle that a French noble by the name of Odo, who was count of Anjou lost his father Robert the Strong.

In 877, Charles the Bald died, and the crown of West Francia bounced from one heir to the next in quick succession. First it passed to Charles’ son, Louis the Stammerer, who died of natural causes in 879. Then it passed to his son Loius III, who died after hitting his head while riding his horse in 882, then to his brother Carloman II, who died after being accidently stabbed by a servant in 884.

Finally, it passed to Charles the Fat who was the son of Loius the German, who Charles the Bald had fought for control of the kingdom.

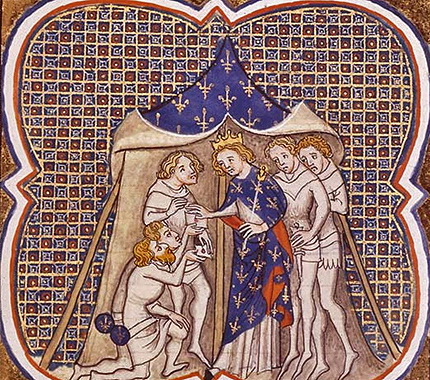

Charles the Fat receives the offer of kingship from two West Francian ambassadors, from the Grandes Chroniques de France (1375-1380)

This unified East and West Francia again, but it was not to last.

In 887 Charles the Fat was overthrown by his nephew in East Francia, supported by the nobility there. He in turn was overthrown by the nobility of Italy and Middle Francia.

Charles was left as king of West Francia, but here the nobility hated him. In 885, Charles had failed to deal with a major Viking attack on Paris, having been begged by Odo, the Count of Anjou and now also the Count of Paris, to help destroy the Vikings. Rather than fight the Vikings, Charles paid them to leave and went back to fighting for his lost territories.

Due to the bravery displayed by Odo against the Vikings during the siege of Paris, he became the most popular noble in West Francia. And so, on 29 February in 888 the Frankish nobility of West Francia overthrew Charles and crowned Odo the King of the West Franks. Odo’s family, the Robertians, and their descendants, the Capetian dynasty, would rule West Francia, or France as it was coming to be known, until 1328.

The Carolingian dynasty would diminish in power and importance until the dissolution of their house in 1120.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend