South Africa’s BRICS connection (or whatever it might rename itself in the wake of this year’s accessions) is the crown jewel of its diplomacy, an indication that the country still matters.

The body is also an expression of what has been called South-South Cooperation: mutually beneficial engagement between developing countries to work on addressing their problems on their own terms, without necessarily following the lead of their more developed peers.

Given that economic progress takes place in particular contexts, such cooperation has much to commend itself, and a recent event put on by the Johannesburg Business School (affiliated with the University of Johannesburg) and the Indian Consulate General in Johannesburg put this in context.

India’s economic trajectory since the 1980s is a remarkable one, and for South Africa, a matter worthy of profound envy – or of emulation if South-South peer learning is to be taken seriously.

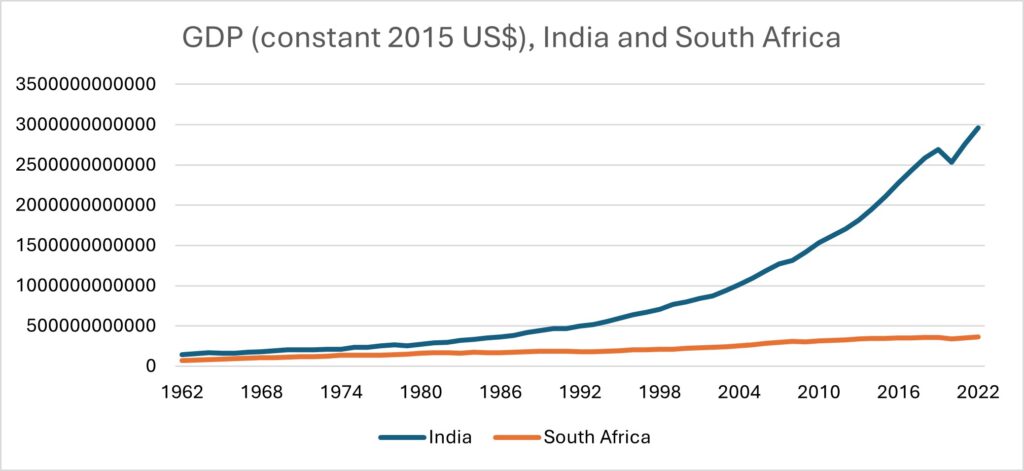

To put this into perspective, look at the relative GDPs of India and South Africa over the past 60 years.

Source: World Bank Database

All protocol observed at the outset: India and South Africa come from different histories and exist in different contexts. India is also a population colossus, with 467 million people in 1962 against South Africa’s under 18 million at the time. Today India’s population approaches 1.5 billion, while South Africa’s closes in on about 60 million.

Yet at the beginning of this period, India’s economy was only roughly twice the size of South Africa’s – around $146 billion to $72 billion (for accurate comparison, the figures used here are constant 2015 US dollars). This ratio stood until the latter part of the 1980s, when the Indian economy began to pull away from South Africa’s. In 1990, India’s GDP was around $465 billion to South Africa’s $186 billion, or a little over two and half times larger. A decade later, in 2000, India’s GDP stood at $800 billion, close to four times larger than South Africa’s at the time: $222 billion.

Eight South African economies

By 2010, the gap had widened further: India’s GDP stood at $1 536 billion (in other words, $1.5 trillion), and South Africa’s at $312 billion, making the Indian economy five times the size of South Africa’s. A decade on from that – in 2022, the last year for which the World Bank database provides information – India’s GDP was $2 962 billion (or close to $3 trillion), against South Africa’s $361 billion. Size-wise, India’s economy is by now equivalent to eight South African economies.

And according to S&P Global Ratings, India is on course to become the world’s third largest economy by 2030. This is no mean achievement for what was for decades a prime example of a developing country (perhaps even a perpetually developing country…).

The numbers alone are impressive, but what they mean was highlighted by Professor Shamika Ravi, an eminent economist and advisor to the Indian government.

A key takeaway from her address was that India’s economic journey has been transformative: not the politicised, colour-coded bean counting that so animates governance in South Africa, but a systemic disruption of what existed before, creating something new in its place. For the majority of the country’s population, this has meant something better.

The flagship data here is the decline in poverty. The international ‘purchasing power parity’ poverty line was set in 2015 at $1.90 a day (2011 prices), which closely aligned with India’s nationally defined poverty line. Recent numbers suggest that India has largely overcome poverty as defined in this way. Poverty in 2011/12 stood at round 12%, and a decade later (2022/23) this has fallen to 2%. Rural poverty has declined to 2.5% and urban poverty to 1%. (Some economists now suggest that India needs a new poverty line to account for its rising prosperity and to set more ambitious objectives.) In South Africa, by contrast, poverty is on the rise, and close to one in five South Africans are estimated to live in extreme poverty.

Crossing the boundary

India has seen its Human Development Index rise consistently since the 1990s, crossing the boundary from a ‘low’ level of human development to a medium level, and with time there is every expectation it will achieve a high level. Over the last two decades, Professor Ravi remarked, the maternal mortality rate has fallen from 301 per 100 000 in the 2001-03 period to 97 in the 2018-20 period. Over the same time span, World Bank data show that infant mortality in India has fallen from 64.4 deaths per 1 000 live births to 25.5 – the latter being marginally better than South Africa’s own, despite South Africa having had a substantial advantage over India in the earlier years.

Amenities such as electricity connections, piped water and connectivity are growing. There has been massive expansion in the proportion of the population that is banked. Unemployment stands at 4.1% (2021/22), and at 12.4% among those aged 15-29. South Africa can only marvel in envy at those figures. India exhibits a determined entrepreneurial spirit – Professor Ravi joked that when she was a student, the cool kids had guitars; now the cool kids have start-ups.

She pointed to one very revealing metric: the occurrence of riots. Riots have a consistent definition that makes them a useful sociological gauge over time. Rioting was on a generally upward trajectory since India’s early years, and peaked in 1981, when 110 361 riots were recorded. Since 1998, Ravi’s work shows, rioting has been in sharp decline, and despite high-profile incidents and media narratives, India has experienced growing stability since the 1990s.

So, what lay behind this?

In a word, growth.

Ignored or disparaged

Too often ignored or disparaged as inadequate or insufficient to deal with social problems as people experience them, growth is the engine that makes social interventions possible. ‘Growth,’ Professor Ravi commented, ‘brings about the kind of changes that affect people’s lives.’

Growth is essentially an increase in the value of economic output over time. It comes about where wealth is invested in hopes of future returns, and wherever more people can become involved in creating wealth. In this respect, India has succeeded where South Africa has not – in recent years at least.

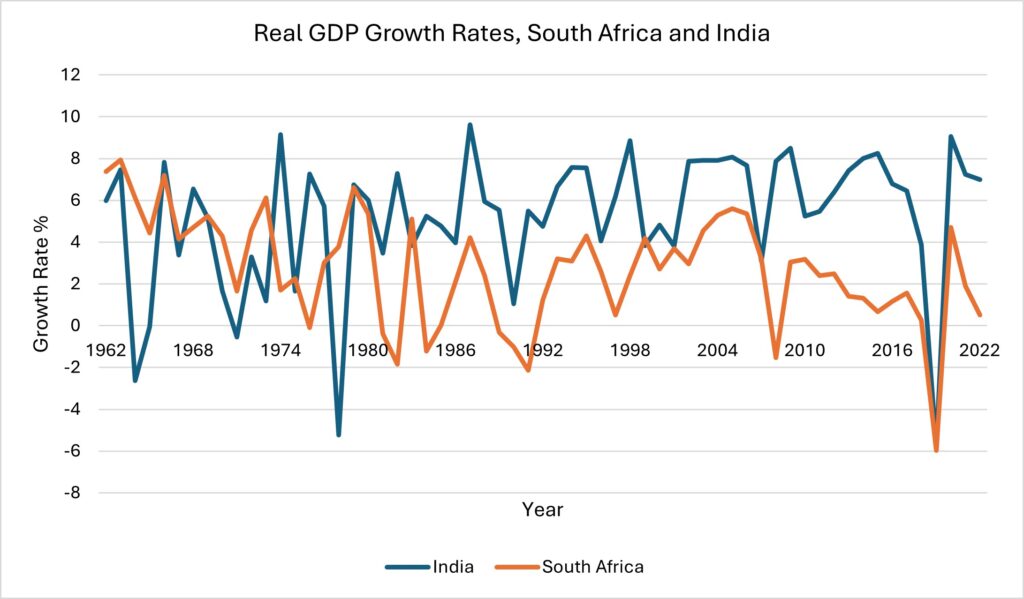

This is illustrated in the graph below.

While both countries have seen considerable variation in their growth rates since the 1960s, the interesting story becomes apparent in the 1980s, as India was able to sustain annual growth rates a good few percentage points higher than South Africa. This became especially pronounced after the turn of the millennium. At this point, growth went into rapid acceleration, or, as Professor Ravi put it, it became exponential.

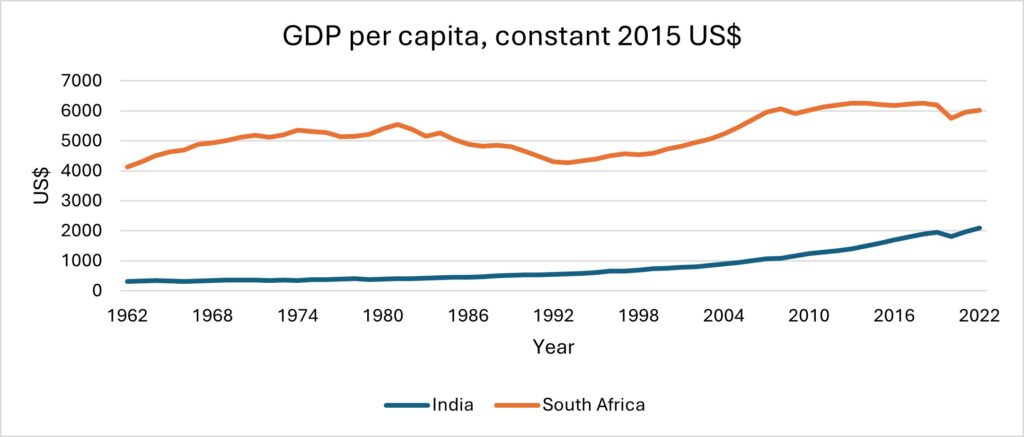

The outcome of this is illustrated below. Per capita GDP shows how wealth generated by growth can be divided among the population, a matter of profound importance for countries with growing populations.

South Africa has a higher GDP per capita than India, significantly so, but the proverbial devil is in the detail. After some progress in the 1990s and early 2000s, South Africa effectively flatlined. India, by contrast, has been on a steady upward trail, and has more than doubled its GDP per capita since the 1990s.

The stock response from cynics is to deride this conclusion as not taking into account the distribution of income. There is some truth to this, but growing wealth has enabled not only welfare spending, but private investments that have created employment.

Moreover, the benefits of India’s growth have been spread across the country, and much of its vibrant digital sector is now happening in its smaller centres.

How, then, did India get there, and are there lessons for South Africa?

Distinct factors

Those are actually two distinct factors. In broad terms, India became receptive to the idea of private enterprise. For decades, it had kept faith in a bureaucratised, poorly managed socialist system. In the 1980s, the manifest failings of this were becoming too obvious to ignore, and a sort of ‘reform by stealth’ began: sympathetic politicians and civil servants began to snip at the frayed edges of the dirigiste economy. In the 1990s, liberalisation became formal, and the so-called Licence Raj – a phrase fusing memories of British colonial control and an intrusive post-independence officiousness – was disestablished.

Professor Ravi then points to 2000 as the inflection point. At this time a liberalised economy and an entrepreneurial mindset were poised to take advantage of the opportunities that a globalised world had to offer.

India’s government had shed its socialist straitjacket and embraced markets. Subnational governments worked to attract investment and reap the benefits. Those that provided better environments for businesses to thrive in reaped the benefits. Demonstration of the effects of policy meant that failures could be discounted and not replicated elsewhere.

And with a long-standing democratic tradition and a free media – and the very real prospect of poorly performing governments being evicted from office – governments took care to ensure that benefits accrued to the population. Democracy for India, messy and rambunctious as it may be, has been an economic and developmental asset.

Whether South Africa can learn from this is another matter. India’s lesson is that growth is the foundation for development, and cannot be compromised, a point that Professor Ravi made repeatedly. Until growth becomes a priority in official thinking – and until there is a proper drive to achieve it – it’s unlikely that South Africa can even begin to make this journey.

Growth follows policy

More trenchantly, India shows that growth follows policy. Being willing to alter mindsets and to dispense with established modes of governance, even where these violate entrenched ideological beliefs, will lead to a reorientation of economic outcomes.

India has done this and continues along this route. As it seeks to expand its presence in the global economy and to secure those benefits for its population, the operative concept is ‘precision policymaking’, which envisages well-crafted, highly competent interventions.

India has accepted and prospered within the global order. It emphatically rejects autarky and embraces globalisation. While its diplomacy pursues global reform – that is part of the purpose of the BRICS group – it accepts the realities of the world and operates pragmatically within it.

All of which seems rather outside the mental framework of South Africa’s authorities at this point. Perhaps we should take heart over the fact that this was once the case in India too. But if South Africa does care to learn from its peers in the Global South, and from India in particular, the lesson is clear: focus on growth, keep the long view in mind and great things are possible.

[Image: Vicki Hamilton from Pixabay]

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend