Next month in Washington DC, some of the world’s most applauded economists, including a few Nobel laureates, will speak at a conference on ‘Rethinking economic policy.’

If anything, the conference shows that many mainstream economists believe a big new push is needed to re-consider some key tenets of the subject. The conference is jointly backed by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a prominent Washington think tank, and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Three forces are behind the rethink. The failure of economists to predict the global financial crisis and ensuing Great Recession that began with the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 raised compelling questions about whether economics could claim to be a science. In science, when experiments are repeated in the same conditions, the outcomes are known.

Another push has come from the pressure of social activists to address climate change and inequality. At issue is how governments might allocate the costs of the transition to a green economy.

Inequality has been a recurrent theme of the ‘Rethink’ conferences that have been held intermittently since 2010. Yet, it is well established that inequality tends to rise with fast economic growth, although the population as a whole usually experiences rising living standards. With revenue from faster growth, a government is in a position to extend public education and healthcare, allowing countries to become a lot less unequal.

The third push comes from the realisation that while economists can advise governments to carry out key reforms to achieve growth, curb budget deficits and cut spending, they cannot advise them on how to deal with the ensuing political costs and opposition. There are usually groups who benefit from change and those who lose, and it can take a long time before the benefits accrue on a wide scale.

Political leadership

Economists might have something to say on the timing and sequence of reforms, but selling a programme really depends on the skill of the country’s political leadership. Many reform programmes stall because benefits do not flow through fast enough, or the timing is wrong.

A former economics professor, Elisabeth Krecké, writing here, sees these conferences as part of a troubling trend towards basing macroeconomics on ideological rather than scientific grounds. She might be partially correct.

The IMF is certainly putting effort into this big rethink exercise, and ahead of the conference, it published an issue of its quarterly, Finance and Development, on ‘Economics, How should it change’. Faced with the onslaught of criticism of the Fund as a neoliberal institution which upholds an unjust world order, the IMF is under constant pressure to show that it is listening to new ideas.

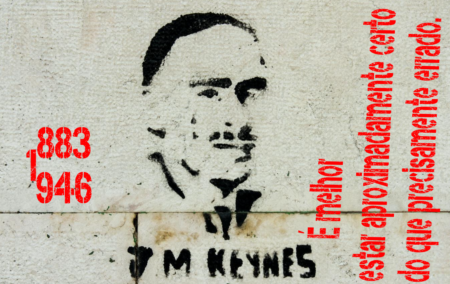

In a tribute after the death of his mentor, Alfred Marshall, John Maynard Keynes wrote that ‘the master economist must possess a rare combination of gifts…He must be mathematician, historian, statesman, and philosopher.’

Today, the economist is more technocrat – a type of engineer, who seeks to maximise the efficiency of an economic system. If they did not study economics as undergraduates, many of the most prominent economists studied maths or engineering.

Changes necessary for reform

It is telling that the now classic explanation of why nations succeed or fail, Why Nations Fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty, was written by two economists, Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson, and was treated as a revelation. Yet political scientists and historians have long studied how wars, revolutions and bargains among the elites have led countries into making the changes necessary for reform and entering into the industrial age.

But for all these gaps, the profession is able to point to trade-offs. It says that if you do not have the right incentives in place you will not grow, or if you borrow too much, you will default.

There are positive aspects to the rethink. Dani Rodrik, a Harvard economics professor, writes that mainstream economics has become closely associated with ‘neoliberalism,’ which favours expanding the scope for markets and restricting the role of the state. Neoliberalism achieved record economic growth in many developing economies and brought about a massive reduction in extreme poverty.

But China, which has brought hundreds of millions out of poverty, relied heavily on industrial policies in state enterprises, rather than a pure version of neoliberal economic policies. The performance of countries such as Mexico, which relied on the neo-liberal playbook, was abysmal, he writes.

‘Universal rules of thumb’

‘The original sin of the neoliberal paradigm was the belief in a few simple, universal rules of thumb that could be applied everywhere,’ Rodrik writes.

Angus Deaton, a Princeton professor and Nobel laureate in economics, writes that the profession has achieved much, ‘yet today we are in some disarray’. He writes that not only did the profession not predict the global financial crisis, but ‘worse still, we may have contributed to it through an overenthusiastic belief in the efficacy of markets, especially financial markets, whose structure and implications we understood less well than we thought.’

He believes that power needs to be better understood. The virtues of free competitive markets and technical change distract economists from the role of power in setting prices, wages, and the direction of technical change and inequality. Deaton sees a role for protectionist policies and limiting immigration to protect, here, the American worker.

And he gives credit to historians who understand that there might be multiple and multidirectional causes. Historians often do a better job than economists in identifying plausible factors that are worth thinking about.

The proposer of an antidote to the big rethink becoming too all-encompassing is John Cochrane, an economics professor at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. For him, the post-Covid 19 wave of global inflation proves that governments sending out cheques and grants to help people over the lockdown results in what economists have long been saying: when demand exceeds supply, there is inflation.

‘In the dustbin’

That means that ideas like modern monetary theory from the left, which says: ‘Prosperity only needs for the government to borrow or print more money and hand it out’, are in the dustbin. You asked for it. We tried it. We got inflation, not boom.

‘Progress in economics has never come from pontificators who urge someone else to throw new ingredients into the pot,’ (like psychology, or mixing politics and economics,) and then ‘stir and hope that a digestible soup comes out.’

The public and economists themselves might expect too much from their subject.

But economics is really about the efficiency with which resources are allocated and the rest is best left to others. Economic forecasting is often problematic, but then economists could never realistically claim to be the soothsayers of our age.

The profession of economist might be in for much bigger changes than are on the conference programme. There is the big question of whether economics, like many other data-driven disciplines, will become a subject within data science.

Will the economy of the future be run by an Artificial Intelligence system that shows, in real time, the governor of the central bank and the finance minister sliders on their screens that they need to tweak to optimise growth and jobs, ensure economic stability and reduce inequality?

[Image: ‘It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.’ John Maynard Keynes, 1883-1946’ r2hox, Eugenio Hansen, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41806381]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend