This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

22nd May 1520 – The massacre at the Festival of Tóxcatl takes place during the Fall of Tenochtitlan, resulting in the Aztecs turning against the Spanish

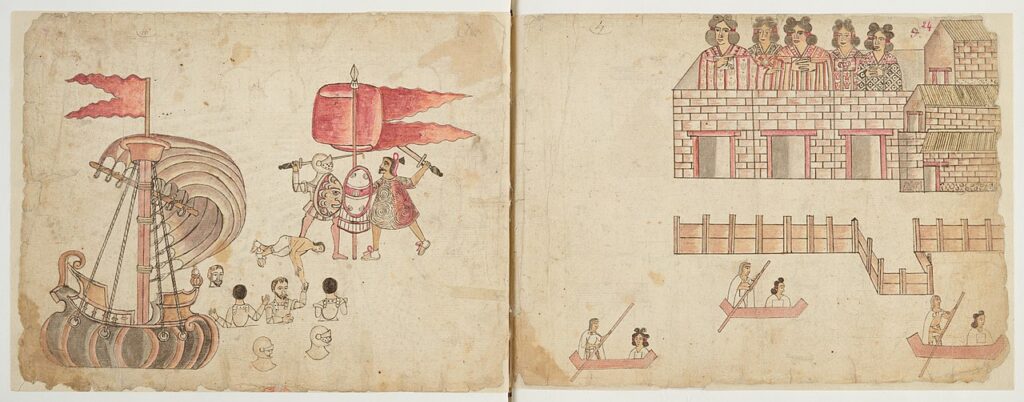

A 17th century depiction of the Fall of Tenochtitlan

Hernán Cortés, was a young man of only 18 when he arrived in the New World as a colonist at the recently established colony on the island of Hispaniola (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic).

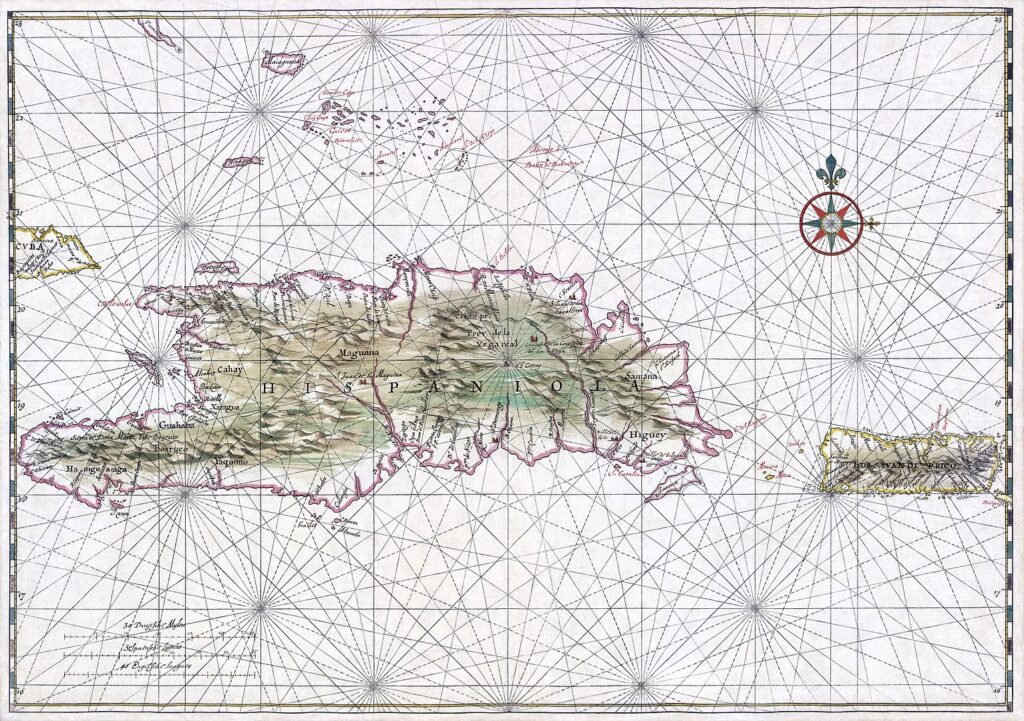

Early map of Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, c. 1639

Cortés soon began a career in the colonial administration, and accompanied the Spanish expedition that conquered Cuba. There he became close to the new governor of Cuba, and married into his family, rising to become mayor of the biggest Spanish settlement on Cuba. Cortés however, had greater ambitions, and when stories of gold and glory reached him from the first Spanish expeditions to Mexico, he set out to secure his slice of this fortune.

Hernán Cortés in 1529

By 1519 Cortés had fallen out with the governor of Cuba, Governor Velázquez, but managed to secure permission from him to embark on an expedition to the mainland of Mexico.

Cortés’s charisma and his cunning allowed him to recruit a large number of soldiers to his cause, assembling a force of some 500 Spaniards and six ships. The governor became worried at this success and tried to order that the expedition be handed to someone else. Cortés ignore this and set sail for Mexico before the governor could arrest him for defying him.

After landing in the Yucatan in Mayan territory, Cortés encountered a Spanish priest who had been shipwrecked there and had learned the Chontal Maya language. The priest joined the expedition as a translator.

Cortés continued to travel along the coast, raiding and trading with local groups. After defeating local people in the region of Tabasco, he was granted 20 women as slaves.

One of them, a local woman from Tetiquipaque, was to become known as La Malinche.

La Malinche, as part of the Monumento al Mestizaje in Mexico City

She spoke the languages of the Aztecs in central Mexico and Chontal Maya, which, with the help of the priest, allowed Cortés to communicate with the local peoples. La Malinche would later become Cortés’s mistress.

In mid-1519, the Spanish force encountered the Totonacs, a subject people of the Aztec Empire. They helped the Totonacs to expel the Aztec tax collectors and established the Spanish coastal port of Veracruz.

In Veracruz, the Aztecs sent envoys to the Spanish, and Cortés asked to see the Aztec emperor, Moctezuma. This was denied. Cortés decided that he would take matters into his own hands, and with his few hundred Spanish troops and some Totonac warriors, he marched on the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.

Along the way he either recruited Aztec tributaries or clashed with them.

One of the largest battles he had was with the Tlaxcala who were an old enemy of the Aztecs.

However, after some initial battles he managed to convince the Tlaxcala that he was their ally, and they would become the strongest supporters of the Spanish in Mexico.

When he arrived at the large Aztec city of Cholula, he massacred a large group of unarmed Aztec nobles to intimidate the Aztecs into not attacking him.

The Spanish entered Tenochtitlan on 8 November 1519 and were received by emperor Moctezuma.

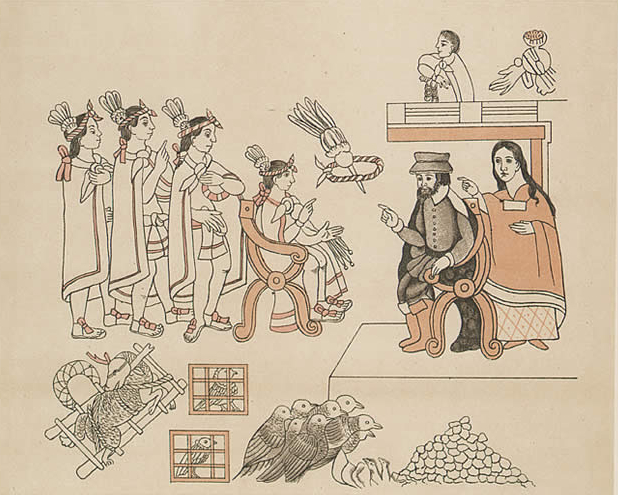

The meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma II, with Malinche acting as interpreter

While a guest of Moctezuma, Cortés heard that some Spanish left behind in Veracruz had been killed by the Aztecs, and in retaliation, Cortés took Moctezuma hostage in his own palace.

In April 1520, the governor of Cuba sent a force of Spanish troops to Mexico to capture Cortés and bring him back to face trial for mutiny in Cuba. Upon hearing this, Cortés left for the coast in the hopes of talking down the force sent to arrest him.

Cortés left Pedro de Alvarado in charge of the Spanish who remained in Tenochtitlan. On 22 May 1520, while Cortés was away de Alvarado heard the Aztec nobility was embarking on a festival of human sacrifice in preparation for an attack on the Spanish.

Conquistador Pedro de Alvarado

Aztec witnesses would years later claim that the Spanish were driven into a greedy lust at the sight of all the gold the Aztec nobility were wearing. Regardless of the cause, the Spanish attacked the Aztec great temple and massacred the nobles there.

This is from an Aztec account of the events, written years later:

At this time, when everyone was enjoying the celebration, when everyone was already dancing, when everyone was already singing, when song was linked to song and the songs roared like waves, in that precise moment the Spaniards determined to kill people. They came into the patio, armed for battle.

They came to close the exits, the steps, the entrances [to the patio]: The Gate of the Eagle in the smallest palace, The Gate of the Canestalk and the Gate of the Snake of Mirrors. And when they had closed them, no one could get out anywhere.

Once they had done this, they entered the Sacred Patio to kill people. They came on foot, carrying swords and wooden and metal shields. Immediately, they surrounded those who danced, then rushed to the place where the drums were played. They attacked the man who was drumming and cut off both his arms. Then they cut off his head [with such a force] that it flew off, falling far away.

At that moment, they then attacked all the people, stabbing them, spearing them, wounding them with their swords. They struck some from behind, who fell instantly to the ground with their entrails hanging out [of their bodies]. They cut off the heads of some and smashed the heads of others into little pieces.

They struck others in the shoulders and tore their arms from their bodies. They struck some in the thighs and some in the calves. They slashed others in the abdomen and their entrails fell to the earth. There were some who even ran in vain, but their bowels spilled as they ran; they seemed to get their feet entangled with their own entrails. Eager to flee, they found nowhere to go.

Some tried to escape, but the Spaniards murdered them at the gates while they laughed. Others climbed the walls, but they could not save themselves. Others entered the communal house, where they were safe for a while. Others lay down among the victims and pretended to be dead. But if they stood up again they [the Spaniards] would see them and kill them.

The blood of the warriors ran like water as they ran, forming pools, which widened, as the smell of blood and entrails fouled the air.

And the Spaniards walked everywhere, searching the communal houses to kill those who were hiding. They ran everywhere, they searched every place.

Cortés returned not long after, having managed to defeat the Spanish force sent to arrest him and having recruited the survivors. He realised that the situation had spiralled out of control while he was away. The Aztecs were rioting against the Spanish and his men were hunkered down in the great palace.

Cortés sent Moctezuma out to calm the enraged Aztec crowds, but he was stoned to death. The Spanish and their allies soon came under attack. On the night of 30 June, Cortés and his men fled the city under heavy attack. Many of them were killed. The survivors would be attacked at the Battle of Otumba on 7 July by an Aztec army numbering around 15,000 warriors.

A late-17th century depiction of the Battle of Otumba

Though the Spanish only numbered around 600, and had about 800 Tlaxcalan allies, they managed to win the battle by using their superior weapons and horses (which the Aztecs had never seen before) to target the Aztec war leaders, routing the opposing army.

Cortés returned to Veracruz and spent the next few months rebuilding his forces and gathering allies from among the Aztec subjects, who were tired of paying tribute in human sacrifices to the Aztec empire.

While the Spanish were gathering their forces, the Aztecs were hit with an outbreak of smallpox – the first ever in the Americas − which weakened their forces.

In May 1521 Cortés returned to Tenochtitlan with an army of around 1,000 Spanish troops and around 200,000 native allies.

A battle on the shores of Lake Texcoco during the Siege of Tenochtitlan

After a brutal siege the Spanish finally captured the city on 13 August 1521.

The Aztec Empire was broken, and the Spanish colony of New Spain, which would one day become Mexico, was established.

La Malinche was to continue as a translator and advisor for Cortés, giving birth to his first child and eventual heir, Martín Cortés. In 1526, she married the Spanish noble Juan Jaramillo and died at a young age in 1529.

Cortés became the first Governor of New Spain with the approval of the King of Spain. He would go on to have a turbulent and eventful career, but eventually died in extreme debt in 1547.

An engraving of a middle-aged Cortés by 19th-century artist William Holl

The Tlaxcalans were rewarded by the Spanish for their help in conquering Mexico and were given the right to carry guns, ride horses, hold noble titles, maintain Tlaxcaltec names and to rule their settlements autonomously. They also assisted the Spanish in their conquest of Guatemala. The Tlaxcala would remain loyal to the Spanish crown, even until the Mexican War of Independence, in which they fought on the side of Spain.

Today they remain a distinct ethnic group within Mexico with about 27,000 people registering in the Mexican census in 2020 as still speaking Tlaxcaltec.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend