This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

22nd August 1485 – The Battle of Bosworth Field

“Battle of Bosworth Field” by Philip James de Loutherbourg, an 1857 engraving after the painting of 1804

The mid- to late-15th century saw a series of chaotic political conflicts in England over control of the throne. These three decades of chaos came to be known to history as the Wars of the Roses.

While the surface level cause of the Wars of the Roses were the questions around succession after the death of King Edward III in 1377, in many ways the conflict was due to the stress brought on the English kingdom by its involvement in the Hundred Years’ War, fought between 1337 and 1453.

John of Gaunt, founder of the House of Lancaster

The struggle was chiefly fought between the House of Lancaster, descendants of Edward’s third surviving son, John of Gaunt, and the House of York, descendants of Edward III’s fourth surviving son, Edmund of Langley.

When Edward died, the throne passed to his eldest son’s son, Richard II, who angered the nobility and was overthrown by a member of the House of Lancaster, Henry IV, a son of John of Gaunt.

During this crisis, the Hundred Years’ War raged between France and England. This conflict was an over-a-century-long attempt by the English kings to claim the throne of France, a brutal series of smaller wars which ravaged France and depleted the wealth of England.

Due to their descent from Norman French nobles, the royalty of England for much of the period between 1066 and 1337 owned significant pieces of land within the kingdom of France, as a vassal of the French Kings, but as the English monarchs were kings in their own right they often had an antagonistic relationship with the French kings.

The constant warfare with France in this period killed off English nobles and depleted the king’s resources. Things were brought to a crisis when the successful King Henry V, son of Henry IV, who won the famous Battle of Agincourt, died of dysentery at age 35 while campaigning in France.

The Battle of Agincourt as depicted in the 15th century ‘St Albans Chronicle’ by Thomas Walsingham

Henry had been on the verge of securing the French throne for the English. Indeed, his son, Henry VI, would be crowned “King of France” and King of England – but he was only nine months old at the time of his father’s death, and thus was a weak king, who had a regency council rule in his place. His reign over France was never truly secured as a result of his young age and his father’s premature death.

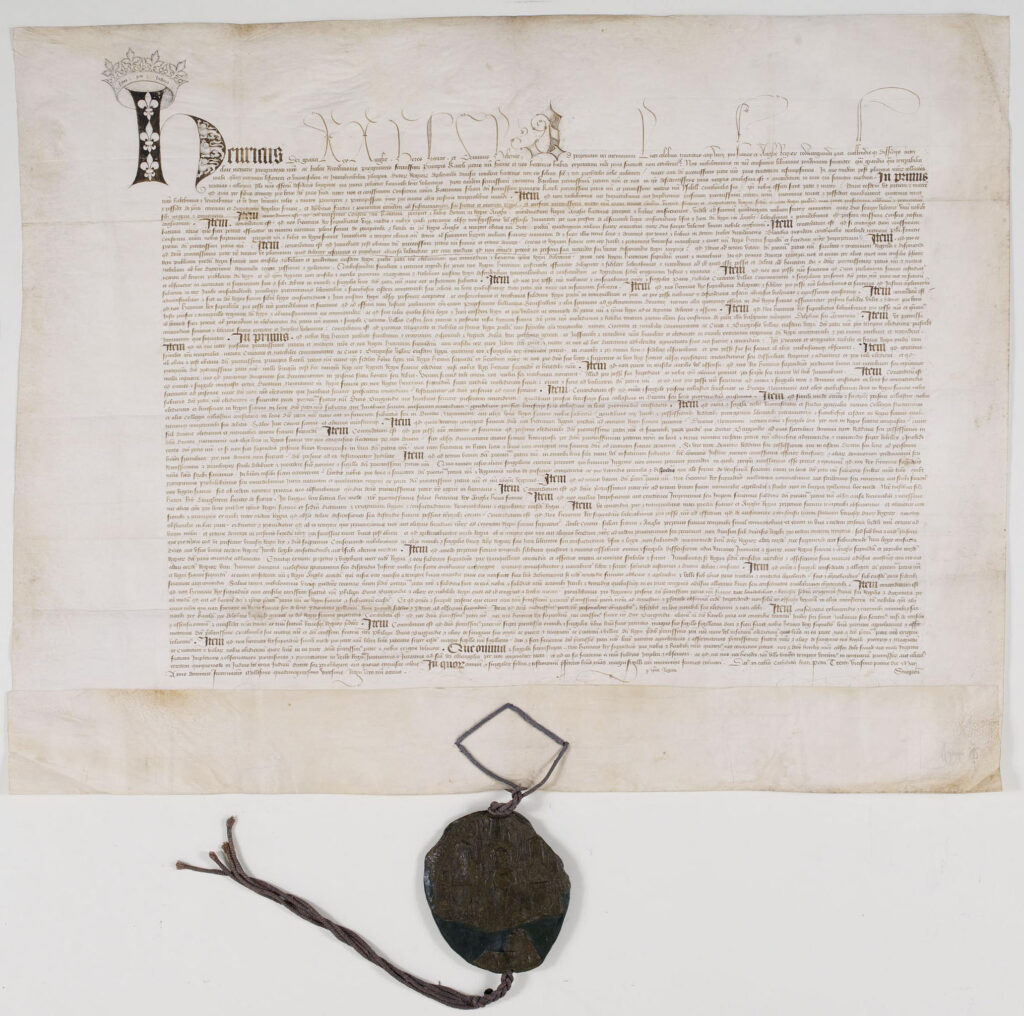

The ratification of the Treaty of Troyes between Henry and Charles VI of France, Archives Nationales

In 1437, Henry VI took power from his regency council and become a fully fledged king. He was, however, nothing like the tough, warlike soldier his father had been and showed little ability as a wartime king. England was also stretched to the breaking point by the decades of war with France, which, despite many English victories, remained a much larger, better-resourced opponent. Henry’s reign saw military setback after setback until finally in 1453 the English lost their territory in mainland Europe, save for Calais.

Richard of York, 3rd Duke of York, the father of Edward IV and Richard III, c. 1445

Henry was already a weak king, and in 1453 he suffered a mental breakdown and became incapable of ruling. The power vacuum this created led to various factions around him fighting for control. The head of the House of York, Richard of York, managed to secure control of the kingdom, had himself declared lord protector of England, and have his sons secured as Henry’s heir. However, Richard was killed on 30 December 1460 in a battle against Henry’s wife, who sought to restore her husband to power. This was short lived and Richard’s son, Edward IV, became king of England in 1461.

Edward ruled England, but became unpopular. He was overthrown in 1470 and had to flee the country.

Henry VI was briefly restored to his throne but remained incapable of ruling and Edward soon returned to England with an army, and smashed Henry’s forces at the Battle of Barnet and then again at the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. At Tewkesbury, Henry’s son, the 17-year-old Edward of Westminster, was killed.

The Battle of Tewkesbury, as illustrated in the Ghent manuscript

Henry died soon after, likely murdered by Edward’s supporters to prevent him being used by disgruntled nobles to overthrow Edward again.

Edward IV would rule until 1483, when he died from an unknown cause. Some suspect poison, while others ascribe it to his lavish lifestyle and overeating. On his deathbed he declared that his brother, Richard, the lord protector of England, was meant to rule the land until Edward’s son came of age. Edward V was briefly made king − but his “protector” Uncle Richard “suddenly” discovered that he and his brother were illegitimate children and therefore could not inherit the throne. Richard then had himself crowned king, as Richard III, in 1483 and had Edward V and his younger brother imprisoned; both soon mysteriously died.

A 1520 portrait of Richard III of England

There was, however, one other major claimant to the throne. A member of the House of Lancaster, Henry, had been taken by his mother to Brittany after the defeat of the Lancastrian forces in 1471. There she slowly gathered allies. Richard III tried to get the Duke of Brittany to hand over Henry and his mother, but negotiations dragged on, and were only agreed when Richard said he would defend Brittany against French invasion. Just hours before the Duke of Brittany ordered Henry to be handed to Richard’s troops, he escaped to France. Henry would be further supported by the French king.

Henry VII (centre), with his advisors Sir Richard Empson and Edmund Dudley

In 1485, Henry, with some English exiles as well as French and Scottish troops, landed in Wales. Gathering some local supporters, he marched to meet Richard in battle.

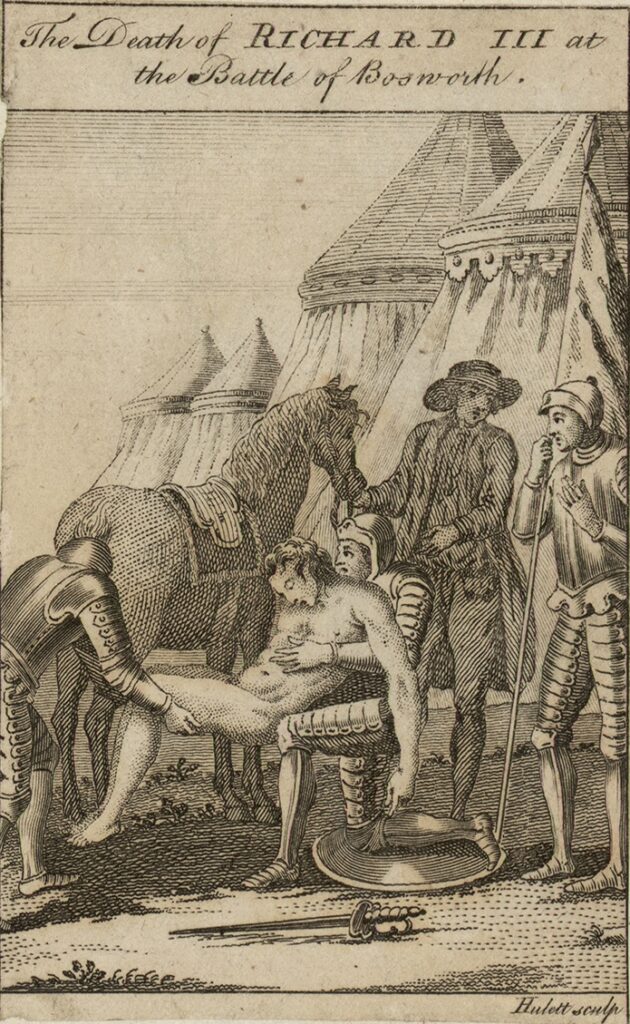

On 22 August 1485, Henry’s forces engaged the army of Richard III and, despite being outnumbered, won at Bosworth Field. Richard III was killed in the fighting.

An 18th century illustration of the death of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field

Henry would now have himself crowned Henry VII of England, and married one of Edward IV’s daughters, Elizabeth of York, thereby uniting again the houses of Lancaster and York, bringing an end to the Wars of the Roses.

Richard III’s body would be swiftly buried after the battle and lost to time. His body was located only in 2012, under a car park in Leicester where once a church had stood.

The skeleton of Richard III [Richard Buckley, Mathew Morris, Jo Appleby, Turi King, Deirdre O’Sullivan, Lin Foxhall – ‘The king in the car park’: new light on the death and burial of Richard III in the Grey Friars church, Leicester, in 1485, taken from [1], CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=64961986]

It was found that before his death Richard had received numerous blows to the head, a wound from a dagger, a strike with a sword to the head. There was also a hole in the back of his head, likely from the blow of a halberd. He was also found to have suffered from an intestinal roundworm at the time of his death.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend