Instead of raising taxes or letting tax cuts expire, Donald Trump is proposing to raise tariffs on imports. “Taxes on other countries”, he calls them.

When Kamala Harris called Donald Trump’s import tariff proposals a “Trump tax”, Trump was incensed.

“Nobody lies like her. She is a liar. She makes up crap. She’s the one gonna raise… You know, she said, ‘Donald Trump’s gonna raise…’ You know why she said I was going to raise…? Because I am going to put tariffs on other countries coming into our country, and that has nothing to do with taxes to us. That is a tax on another country.”

Trump wants to institute blanket tariffs of up to 20% on all imports and additional tariffs of 60% to 100% on Chinese imports but has dismissed claims that this will lead to higher consumer prices.

Trump and Harris face each other in the US election on 5 November 2024, although early voting in at least three states begins later this week.

Let’s leave aside the hypocrisy of Trump calling anyone else a liar when he stood on a debate stage just last week dropping clangers like Democrats want to legalise “post-birth abortions” (which was debunked back in 2020) and Haitian immigrants are killing and eating household pets in Springfield, Ohio (they are not).

Let’s leave aside Trump’s running mate’s frank admission that he had to “create stories” to get the media’s attention and highlight the “suffering of the American people”.

The notion that import tariffs are “tax on another country” is laughably incorrect.

How import taxes work

Import tariffs are paid by the importer, not by the exporter in another country.

That exporter is highly unlikely to lower their prices to make up for an importing country’s tariffs, especially when their products are in demand in large part because of their low price to begin with.

Being paid by the importer, this means that the importer will have to raise the sell-on price of the product by the amount of the tariff, in order to maintain their profit margin. It will be a rare tariff that gets eaten entirely by the importer.

That, in turn, means that the prices of imported goods will rise. Next to revenue generation, that is, after all, the purpose of a tariff. They’re supposed to make imported products less price-competitive against locally produced alternatives. They’re supposed to permit local producers to raise their prices to the tariffed price of competing imports.

And, because these higher prices affect all of the buyers in the importing country, that means it acts like a regressive tax that falls hardest on the lower and middle classes.

Just like South Africa’s 40% import tax on textiles means poor people must pay 40% more for clothes for their children, Trump’s import tariffs will increase prices for ordinary Americans.

Harris’s tax plan is to tax the rich and ease the burden on the middle class. Trump’s plan is to tax imports, instead, which hits the poor the hardest.

Consumers will pay

Don’t just take my word for it. Let’s buttonhole some economists and trade analysts.

“If President Trump raises tariffs on imported goods, it means inevitably that American consumers are going to pay more,” Howard Gleckman, senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, told CNBC.

“Ultimately, the cost of tariffs will be paid by us, the consumer,” George Ball, chairman of investment management firm Sanders Morris, said in the same article. “They’ll be buying things at higher prices than they otherwise would.”

It not only leads to rising prices in the importing country. Again via CNBC: “Typically in a situation where a country is imposing a number of new tariffs, what you tend to see is reaction from the other countries that are impacted,” says Sam Millette, director of fixed income at Commonwealth Financial Network.

“That creates a trade war. And effectively, what that does is create a situation where both impacted countries are seeing this government intervention. It tends to lead to higher prices for consumers in both countries.”

More harm than good

“[T]hese policies do more harm than good, undermining the very people they are designed to protect,” writes Vance Ginn, founder and president of Ginn Economic Consulting and an associate research fellow with the American Institute for Economic Research. “Tariffs are taxes on imports; like all taxes, the costs are inevitably passed down to the consumer. When the federal government imposes tariffs, it raises the prices of goods that many American businesses rely on, leading to higher costs. This isn’t just an abstract economic concept — it affects every American who buys a car, electronics, groceries, or other everyday items.

Ginn explains that tariffs do not actually fulfil their intended purpose of protecting and revitalising domestic manufacturing capacity.

“Proponents of tariffs often argue they are necessary to rebuild America’s manufacturing sector, but the problem isn’t foreign competition – it’s at home,” he writes. “US manufacturers’ core issues stem from excessive government spending, high taxes, inflated minimum wages, overregulation, and a lack of right-to-work laws. Instead of addressing these root causes, tariffs exacerbate the problems by acting as an additional tax on American businesses and consumers.”

And further: “Take, for example, the tariffs on steel, which were implemented to protect US steel producers. While they may have helped some steel manufacturers, they raised costs for industries that depend on steel, such as the automotive and construction sectors. These industries were forced to pass on these costs to consumers, making American-made goods more expensive and less competitive. Rather than revitalizing manufacturing, these tariffs hinder growth, slow job creation, and harm consumers.”

Economists agree

Business columnist Michael Hiltzik, for the Los Angeles Times, writes that JD Vance, Trump’s running mate, claims that “economists really disagree about the effects of tariffs.”

They don’t, Hiltzik says. “In truth, there’s no detectable disagreement among economists. In two polls conducted by the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, panels of economists unanimously agreed that American households would pay the price for Trump’s tariffs.”

By way of example, Hiltzik pointed to tariffs introduced during Trump’s first term as president, when he started an aggressive trade war, primarily against China.

“The Trump tariff on washing machines had a measurable effect on the American market… Chinese-made machines commanded 80% of the U.S. market in 2018. That January, Trump imposed a 20% tariff on the first 1.2 million imported washing machines per year, and 50% on the excess imports. Economists at the Federal Reserve and University of Chicago calculated that as a result, the price of washing machines rose by about 11%, or an average of $86.”

He continues: “As it happens, the price of clothes dryers, which weren’t subject to a tariff, also rose, by $92. The reason evidently is that washers and dryers are generally bought as a pair; washer makers taking advantage of the reduction in foreign competition to raise prices on that appliance simply jacked up prices on the package.

“Overall, manufacturers passed through more than 100% of the tariff cost to consumers, thanks to the lack of competition and the price increase on dryers. American consumers lost about $1.55 billion because of the washing machine tariffs, the authors found.” (My emphasis.)

Foreign policy

Trump has also launched a broadside against foreign countries that have started to use each other’s currencies for trade, instead of pricing exports in US dollars. He says he’ll slap a 100% tariff on trade with the US against such countries – which could well include South Africa.

A further threat to South Africa’s trade with the US (which is its second-largest trading partner after China) is that it currently enjoys special access under the African Growth and Opportunity Act. An aggressive foreign policy that punishes countries over their bilateral relations with perceived enemies of the US could have severe consequences for South African exports to the US.

Economists at Goldman Sachs ran scenarios for Trump’s policies – keep tax cuts in place but raise tariffs and tighten immigration – and those of Harris – raise corporate taxes and taxes on the rich, but increase spending and expand middle-income tax credits.

They conclude that Trump’s tariff plan and immigration policies would cause a hit to GDP growth, while the plans of Harris would slightly increase GDP growth.

Imports and exports each raise the standard of living for participating countries. They benefit both countries in an exchange, just like a transaction between two people benefits both parties. The more free trade is, the higher the aggregate gains from international trade.

Given that either Trump and Vance do not understand even the basic economics of import tariffs, or they deliberately “create stories” to misrepresent their effect, one can only wonder what other magical thinking or economic skulduggery they have up their sleeves.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend

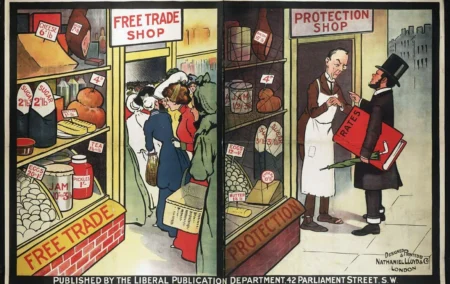

Image: Political poster from the early 1900s illustrating by analogy the differences between free trade and protectionism. The free trade shop is full of customers attracted by its low prices. The protectionist shop has higher prices and few customers, with animosity between the business owner and the regulator. Source: Wikimedia