This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

22nd January 1863 – The January Uprising breaks out in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. The aim of the national movement is to rescue the Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth from occupation by Russia

At the end of the 18th century, the once mighty Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (PLC) was crumbling. During the mid-17th century, the Polish king had been forced to grant the powerful Polish nobility the right of veto over any decision in the Commonwealth parliament, the Sejm. This power, known as the liberum veto, was at first seldom used – but became more and more widely used until it became a regular feature of Polish politics. As a result, over a third of all sittings of the Sejm were entirely incapable of passing any legislation, as the veto nullified not only that which was vetoed but also the entire session.

This power would be abused by Poland’s powerful neighbours, the Austrian Empire, the Kingdom of Prussia and the Russian Empire, as a way to paralyze and prevent the PLC from resisting their encroachment on its sovereignty.

By the mid-18th century, the PLC was in large part a puppet state of the Russian Empire with the Russian Tsar largely dictating the internal politics. Polish kings were only chosen if the Tsar agreed.

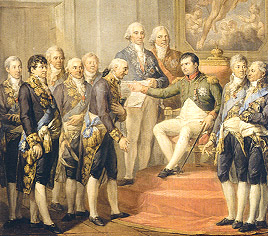

The PLC began its death spiral when the Prussians, Austrians and Russians agreed in 1771 to partition large pieces of PLC territory, as part of efforts by the Prussians to prevent Austria following Russia’s example and attacking the now weak Ottoman Empire. By carving up the PLC, the three empires would all feel secure in the expansion of their power.

In 1772, Austrian, Russian and Prussian troops marched into PLC territory and despite some resistance quickly occupied large parts of the country. Within a year the Polish Sejm was forced to recognise this occupation and the PLC lost 30% of its territory and a third of its population.

Things were soon to change in Europe as the French Revolution in 1789 – and, in the previous decade, the American Revolution in 1776 – created a climate of radical change across Europe and the Americas. The PLC was not immune to this change and many Polish intellectuals had, ever since the partitions, been keen on radical reform.

These reforms found their expression in the Constitution of 1791, the product of a four-year sitting of the Sejm. The Constitution was based largely on the Constitution of the United States, which had been recently ratified, and had similar features (such as a division of power between three branches of government and a bi-cameral legislature) to the US document.

The Constitution also granted equal rights to Jews, allowed freedom of religion (although the Catholic religion would be first among equals) allowed townspeople to become officers in the army and made it much easier for townspeople to become nobles (the only people with full political rights). Notably the Constitution’s definition of citizenship included townspeople and peasants for the first time in Polish history.

The new liberal reforms of the PLC horrified the surrounding Prussians, Austrians and Russians, who were all dominated by very conservative centralised monarchies. In 1792 the Russian Empire invaded as part of efforts to bring its puppet state back into line and roll back the reforms. The PLC had allied with Prussia in the aftermath of the first partition and so the Prussians threatened to intervene.

The Prussians offered the Russians a deal; if they divided the PLC between the two of them and destroyed the Polish state entirely, the Prussians would side with Russia and not intervene. So it was that in 1793, the Russian Empire and Kingdom of Prussia would jointly annex even more of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.

An uprising of the Poles against this partition a year later saw the final crushing of the Polish state and its absorption into the Russian and Prussian empires in what is called the third partition of Poland.

Poland was briefly resurrected by Napoleon as a puppet state during his domination of Europe as the Duchy of Warsaw but was destroyed after Napoleon’s failed invasion of Russia in 1812.

In 1815, the territory of the Duchy of Warsaw was made into a new ‘Kingdom of Poland’ – a constituent part of the Russian Empire, with the Tsar also holding the title of King of Poland – which would, in theory, have some autonomy that normal imperial provinces did not have, being governed under a more liberal constitution than the rest of Russia.

In reality, however, the Tsars ruled the territory much as they did the rest of Russia – not respecting the limits on their power within Polish territory. Historically this Kingdom of Poland is usually known as ‘Congress Poland’.

When Tsar Nicholas I came to the throne in 1829, he adopted a more autocratic approach than his predecessor, and also supported the Orthodox Church more strongly, at the expense of the Catholic Church. Discontent with this state of affairs and growing Polish nationalism led to the ‘November Uprising’ against Russian in 1830.

The rebellion ultimately failed to gain much international support and became internally divided between radicals and moderates. It was eventually crushed by the Russian army, resulting in a further loss of Polish autonomy.

While the armed uprising had failed, Polish nationalist resistance had not been stamped out by the Russians and would continue to bubble under the surface within Congress Poland for the next three decades.

The setbacks for the Russian Empire during the Crimean War against the French and British and the success of the Italian independence movement in driving the Austrians from the Italian peninsular encouraged another uprising.

The pro-Russian head of the Polish civil administration, Aleksander Wielopolski, feared the possibility of an uprising and so tried to weaken the nationalists by introducing the conscription of young Polish men into the Imperial Russian Army for 20 years of service.

This had the opposite effect, triggering a backlash by the potential conscripts who revolted and were soon joined by the nationalists.

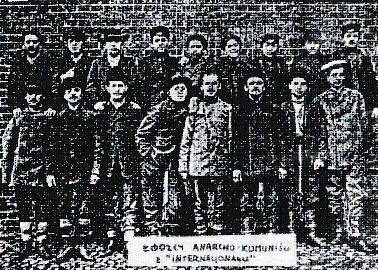

On 22 January 1863, what to be known as the January Uprising began.

The Poles were joined by international volunteers from Italy, France, Hungary and the British Empire as well as by some Russian liberals and rebels in Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine.

The British, French and Austrian governments expressed some support for the Poles but gave little actual material support.

The Prussians, however, fearing the Poles might be joined by Polish rebels in Prussian territory, strongly supported the Russians against the rebels.

Without proper foreign support and with internal divisions between land owners and peasants among the rebels, the rebellion was crushed after a year.

Hundreds would be executed and tens of thousands exiled to Russian settlements in Siberia.

The defeat of the uprising would suppress the Poles for 40 years with the next armed uprising being the Łódź insurrection in 1905, which also failed.

Poland would eventually regain its independence during the break-up of the Russian Empire in the aftermath of the First World War.

The centuries’ long fight for Polish independence from its neighbours is reflected in the national anthem of the modern Polish state, a song first sung by Polish troops fighting for Napoleon’s armies in Italy. The English title of the song: Poland is not yet lost

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend