A good society is one that does not impose obligations on future generations, it is a society that transfers a portion of the wealth generated by previous generations to future ones and grows the absolute size of this portion. In simple terms, a good society values savings over debt.

In South Africa, if one looks at the data, households have been struggling to save since at least the 90’s or even before. One of the reasons given for why we need a state bank is the prohibitively high cost of capital, yet like any economic good, the more capital is supplied by the market, the cheaper the price of that capital. The price of capital in this case being interest rates, and the supply being represented by the quantity of savings in the economy.

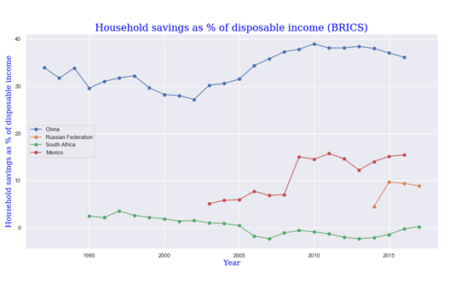

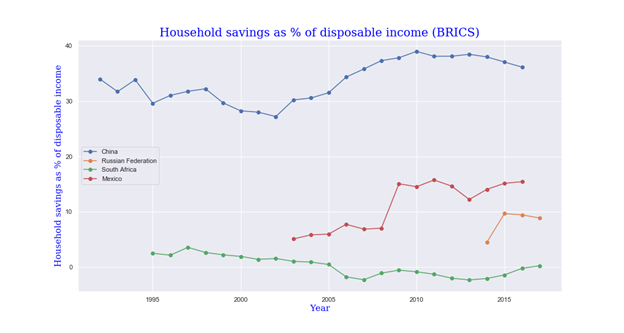

South Africa is a net capital importer, as reflected in our trade deficit. South African households save one of the lowest proportions of their disposable incomes of any emerging country, according to OECD data.

The above graph uses the aforementioned OECD data on the percentage of household disposable income that is saved. As we can see, for the countries in BRICS for which the OECD has data, South African households save the lowest proportion of their income. In fact, between 1997 and 2007, this percentage was in a sustained decline, eventually going negative.

When the percentage of disposable income households save goes below zero, this can only mean households are going into debt instead of saving for the future. In South Africa it slipped below zero for the first time in 2006, and stayed there until 2016. This is a disaster for an emerging country like South Africa.

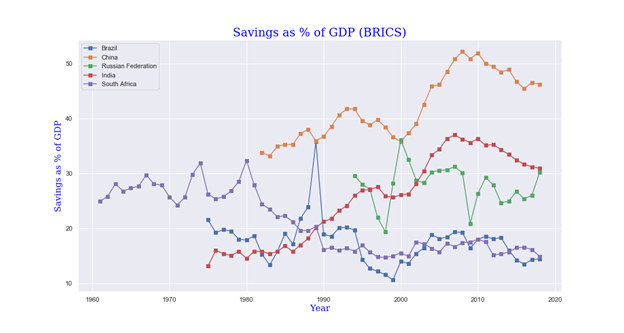

Of course, household savings are not the only savings available in the economy. Businesses, NGO’s etc also save. To get a better picture of savings in South Africa as compared to our emerging market peers, we have to look at gross savings as a percentage of GDP. The world bank provides the data.

The world bank, luckily, has data for the whole of BRICS. South African savings as a percentage of GDP tended to increase (notwithstanding its cyclical nature) from the 60’s up to 1980 where it peaked at 32%. After that it experienced what can only be described as a precipitous decline, decreasing by more that 50% until the 90’s where it has been range-bound between 15-17.5% of GDP ever since.

South Africa, yet again, significantly underperforms the rest of BRICS. Managing only to beat Brazil. India and China in particular are two of the countries that have seen incredible GDP growth over the past few years, it seems not unreasonable to assume that part of this economic success is a result of having a high savings rate. This enables local capital formation, it reduces the need to import capital, thus helping to ease the trade deficit.

Consumption does not create sustainable economic production. If government policy encourages consumption of what has been saved in the past, instead of promoting savings, investment and production, then we cannot leave a prosperous legacy to our children. In South Africa, the combination of high taxes (income taxes in particular) and looser monetary policy (the prime lending rate has been trending downwards since at least the year 2000) has discouraged savings.

While the government has implemented some good policy measures such as the tax free savings account, proposals to further discourage savings are being proposed. These include using private and state pensions to bailout SOE’s. Undermining the security of the pension savings of South Africans will not help us catch up with our emerging market peers when it comes to savings, investment and ultimately growth.

This expropriation without compensation of pension funds, going by the benign-sounding name of prescribed assets will further reduce the propensity of South Africans to save, and make us even more dependent on attracting foreign investment.

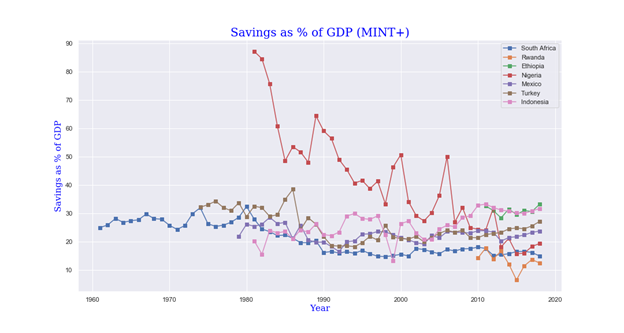

The above chart is also based on World Bank data. It shows South Africa’s savings as a percentage of GDP, compared to MINT (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey) countries plus Rwanda and Ethiopia, two of the fastest growing African countries. Again, South Africa comes out near the bottom, just exceeding Rwanda’s savings rate in 2018. Nigeria is higher than South Africa but if this data from the world bank is to be believed, they have fallen from their peak in the early 80’s as South Africa did, but their fall has been even greater than ours, falling from a rate close to 90% to just under 20% in 2018.

Savings are important for an emerging economy, especially one that has ambitions of building up its capital stock. This capital stock requires the availability of capital at a reasonable cost, and the way to supply the market with capital is through savings. Once savings increase, interest rates (as set by the market, not central banks) should start to decrease since available capital is growing faster than the demand for the capital.

Without an economy that encourages savings, it will be much harder to promote the manufacturing sector as the government claims it wants. Of course, savings are not the only reform needed, you also have a labour regime that drives up the cost of labour. It is simply that without savings, it is much harder to eliminate a trade deficit, it also means that our children will not receive much help from us when they have to start paying off some of our accumulated debt, especially the sovereign debt.