This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

31st October 1922 – Benito Mussolini is made Prime Minister of Italy

Once hailed by many as the darling of Europe, a man famous for allegedly getting the trains to run on time, Benito Mussolini was in the end shot by his own people and hated by the world.

Mussolini was born in 1883 in Dovia di Predappio, a small town in Romagna, Northern Italy. His father was a socialist blacksmith and his mother a Catholic school teacher. Working in his father’s forge as a teen, Mussolini would become very influenced by his father’s political views, which were proudly Italian, socialist in their economic outlook and glorifying of militarism. Due to his father’s atheist views, he would not be baptised until he was an adult. His mother managed to have him sent to a Catholic school where he eventually qualified to teach school children in 1901.

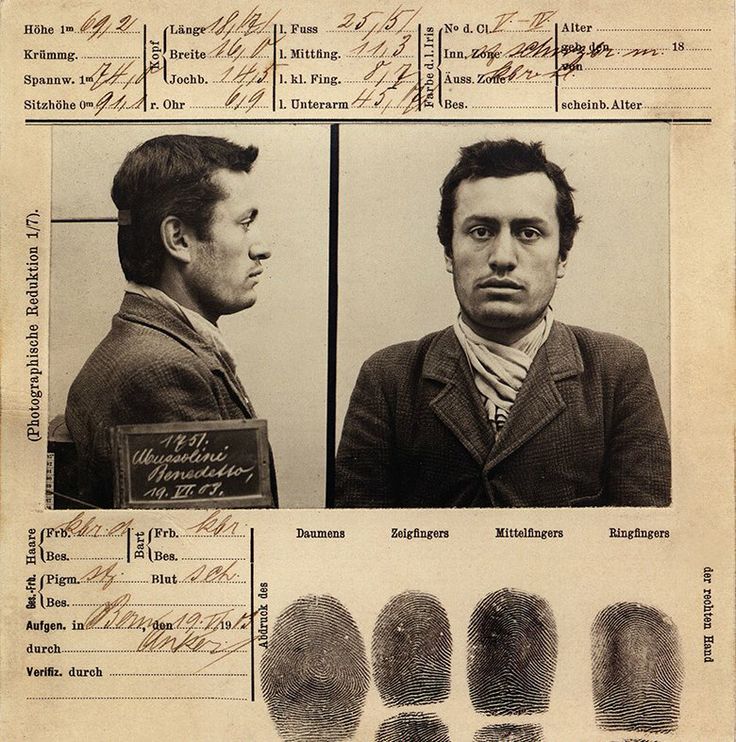

Seeking to avoid conscription in Italy, Mussolini moved to Switzerland in 1902, where he drifted about not finding any meaningful employment. Later on, Mussolini would join the socialist movement in Switzerland, becoming a local organiser and worker for a socialist newspaper. He was expelled several times from Switzerland for encouraging violent strikes.

In 1904, Mussolini returned to Italy and, to avoid punishment, had to serve in the army. In 1906 he returned to teaching.

Three years later he moved to the Austro-Hungarian city of Trento (now in Italy) where he once again became involved with the local socialists. Only a year later he moved back to Italy to edit a socialist newspaper called The Class Struggle.

During this time, he wrote many articles critical of the church and priesthood and tried to establish himself as a socialist intellectual. He became strongly anti-Catholic in this period. In 1911 he was jailed for a riot protesting the ‘imperialist war’ following Italy’s invasion of Libya (covered in an earlier This Week in History).

At the start of the First World War in 1914, the Italian Socialist Party decided to oppose Italy’s involvement. At first, Mussolini toed the party line, but, later coming to view the war as a way to liberate Italians living in Trento and the surrounding area from Austrian control, he began voicing his support for the war. Mussolini justified his change of heart to the party by claiming that the Central Powers (Austria-Hungary, Germany and Turkey) were reactionary imperialists and so it would aid socialism to join the fight against them. Mussolini at this time began to move strongly against pacifist views held by many Italian socialists, and was as a result ejected from the party.

Founding a new paper, Revolutionary Fasces for International Action, to express his ideas, he shifted his ideological focus away from class struggle towards a kind of national socialism. In this view, the vanguard party which would lead the revolution could be drawn from the best of all classes rather than just the lower classes, as orthodox Marxists believed, and work to unify all of society into a harmonious state which would work seamlessly towards shared greatness.

Mussolini and his followers began to refer to themselves as Fascisti – or, as we know them today, Fascists.

In 1915, Mussolini was called to military service and was greatly praised by his commanders, earning promotion.

He would be wounded in the fighting in 1917 and sent home from the war.

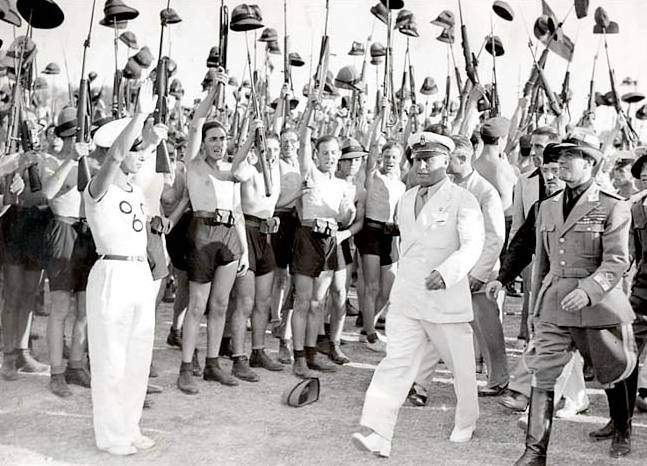

By 1919, Mussolini had decisively broken from orthodox socialists and now denounced socialism as a failed doctrine. His first step was to launch a militia group, the Italian combat squad. In time, this would develop into a militia called the Blackshirts, which would enforce the Fascists’ will. In 1921, the Fascists formed a political party, with Mussolini being elected to the legislature.

Between 1919 and 1921, the Blackshirts would fight socialist politicians and militias across Italy and also participate in breaking socialist strikes by threatening the workers. In this way, the Fascists expanded their influence, and gained supporters amongst anti-socialist Italians.

In 1921 the Fascists joined a coalition with other anti-socialist parties to form a government, but after only a few weeks withdrew their support for the liberal Prime Minister, Luigi Facta. The socialists and liberals tried to form a government and dissolve the Blackshirts, but this provoked street protests by the fascist militia, and failed.

The next year Mussolini organised a huge march of Fascists, beginning in Naples, to demand the resignation of Prime Minister Facta.

This group, which included scores of armed men, was essentially an army. Prime Minster Facta sought approval from King Victor Emmanuel III to declare martial law and send the army to defeat the fascist marchers, but the king feared a civil war and refused to give his consent. Shocked by this decision, Facta resigned and, on 31 October 1922, the king appointed Mussolini as Prime Minister. From this point, Mussolini quickly grew his power; by 1927, he had become Italy’s unchallenged authoritarian leader.

Mussolini crushed all opposition, nationalised large parts of the economy, enlarged the armed forces, redistributed land to peasants, carried out large infrastructure projects – building railways and draining marshes –and established a cult of personality around himself, and all with the ultimate goal of Fascism in mind … ‘everything inside the state, nothing outside of it’.

His policies drove the country deep into debt and the economy faltered under his rule.

In the 1930s, the rise of aggressive, fascist militarism in Germany under the Nazi party alarmed Mussolini, who proposed an alliance with France and Britain, as had existed during the First World War.

At that stage, however, these countries were interested in seeking peace with Hitler and so rebuffed the Italian. Mussolini turned instead to the Germans, joining them in 1936 in the Axis alliance.

In the same year, seeking to avenge the Battle of Adwa and grow Italy’s colonial empire, Mussolini invaded Ethiopia, using poison gas on the defenders to break their morale.

In 1939, seeking to expand Italian influence across the Adriatic Sea Mussolini invaded and subjugated Albania. In 1940, Italy entered the Second World War on Germany’s side, invading French territory and British-controlled Egypt. Despite Italy’s huge army, its rapid expansion without a supporting industrial base had left the army poorly supplied and equipped, and it suffered humiliating defeats against the British and French. In late 1940, the Italians invaded Greece and, once again, suffered many defeats, and only saved from embarrassment by German reinforcements.

As the war dragged on, Mussolini became more and more beholden to his German ally. When, in 1943, Mussolini defied the Italian king’s ousting him from power during the allied invasion of Italy and was arrested and jailed, he was sprung from imprison by German troops.

Italy then switched sides in the war, prompting the German forces in Italy set up a puppet government in northern Italy with Mussolini as its leader.

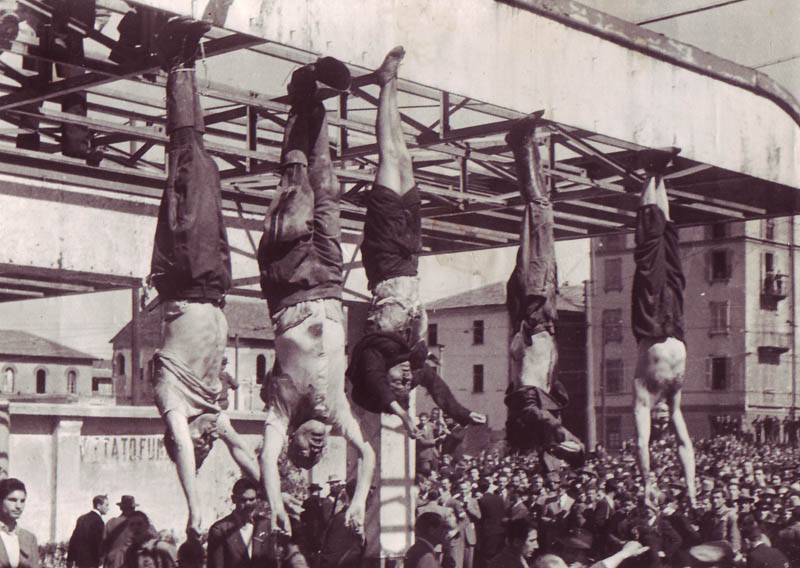

As the end of the war neared in early 1945 and Germany’s and Mussolini’s armies began to collapse, the Fascist leader – who had styled himself Il Duce – tried to flee the country. However, he was captured by communist partisans and shot on 28 April 1945. His corpse – along with those of his long-time mistress, Clara Petacci, and several of his lieutenants – was hung upside down in a square in Milan so that people could see he was dead.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend