Classical liberalism is under assault from both the left and the right. It has fought and defeated left-wing threats (communism) and right-wing threats (fascism) before, and it will have to do so again.

‘An objection the [IRR] has increasingly faced in recent years’, wrote Rebecca Davis in Daily Maverick, ‘is that the Institute appears to be taking on the concerns and values of the American right wing…’

Well, what exactly are those values, and how do they square with the classical liberalism that the IRR espouses?

For answers, we can start with an editorial leader published in The Economist newspaper this past weekend, entitled The threat from the illiberal left. The article should be available with a free registration, but here’s an archive link that should work.

The article notes that liberalism, over the past 250 years, has brought about unparalleled progress. In no small measure, The Economist itself, founded in 1843, has played a major role in the establishment of liberalism – political, economic and social liberalism – as the ideological lodestones of modern democracies.

A marvellous recounting of the newspaper’s first 150 years can be found in The Pursuit of Reason: The Economist 1843-1993. It chronicles the development of classical liberalism as much as it tells the story of the newspaper, and I highly recommend the book.

Classical liberalism favours the rule of law, free markets and private property rights, world peace through free trade, free immigration, deregulation, and constitutionally-guaranteed civil rights. In liberal democracies, it has brought about unprecedented peace, prosperity, freedom, and equality before the law. Around the world, it has dramatically reduced poverty and hunger, and improved basic living conditions.

A century ago, classical liberalism was threatened by both communism on the left, and fascism on the right. This conflict would play itself out through two World Wars and the Cold War, before economic and political liberalism triumphed in what Francis Fukuyama famously described as the ‘end of history’; that is, the final form of government upon which the developed world universally came to agree, and upon which it was not possible to improve.

That isn’t to say, as Fukuyama noted, that liberal democracies were without injustice or social problems, but that these problems were rooted in inadequate implementation of the principles of liberty and equality on which modern democracies are founded, and did not imply that these principles were inherently flawed.

Nowadays, The Economist points out, liberalism faces similar threats from both sides, as it did in the 20th century.

The newspaper glosses over the threat from the Trumpian right in a single paragraph in order to get to the subject of its title, the illiberal left. It explains in some detail why the rise of the illiberal left is a threat to classical liberalism, and that alone makes the article a great read.

About the right, it says: ‘The most dangerous threat in liberalism’s spiritual home comes from the Trumpian right. Populists denigrate liberal edifices such as science and the rule of law as façades for a plot by the deep state against the people. They subordinate facts and reason to tribal emotion. The enduring falsehood that the presidential election in 2020 was stolen points to where such impulses lead. If people cannot settle their differences using debate and trusted institutions, they resort to force.’

That is as good a summary as any for why the modern American right cannot be reconciled with the classical liberal principles to which the IRR hews.

The right claims to stand for small government, but in reality it never does, preferring instead to sustain a ‘crony’ relationship between big business and the state, just favouring businesses different from the ones the left favours.

The right often calls upon government to impose conservative, traditional or religious values upon people by force.

The right challenges electoral defeat by violently interrupting the formal count and endorsement, and then claiming that the election was stolen.

The right has become mired in conspiracy theories, believing their political opponents to be involved in clandestine criminal operations ranging from electoral fraud, to mind-control by vaccination, to child abuse rings.

The right is just as good at identity politics as the left, lobbying for group rights and recognition of group identity instead of advocating for individual rights, as liberals do.

The right objects to liberal policies on gay rights, women’s rights or the rights of black people by saying that protecting the rights and liberties of other people infringes their own rights or threatens their own ‘culture’. The right is xenophobic and intolerant.

Right-wing populists like Hungary’s Victor Orbán have openly promoted the idea of ‘illiberal democracy’ among the right, trying to smear liberal democracy as a project of the left.

The illiberal right is as dangerous to classical liberal principles as the illiberal left is, and for much the same reason: on both sides, they either believe that their political aims ought to be furthered by means of a powerful, benevolent state, or they are paranoid, thinking that global elites are conspiring to deprive them of their liberties.

‘If classical liberalism is so much better than the alternatives, why is it struggling around the world?’ asks The Economist. ‘One reason is that [right-wing] populists and [left-wing] progressives feed off each other pathologically. The hatred each camp feels for the other inflames its own supporters – to the benefit of both. Criticising your own tribe’s excesses seems like treachery. Under these conditions, liberal debate is starved of oxygen.’

Another effect of this polarisation is to denounce every policy position you disagree with as equivalent to the worst traits of your political opponents. That is why liberal policy positions that threaten the illiberal left get caricatured as ‘literally Hitler’, and why liberal policy positions that threaten the illiberal right get caricatured as ‘literally Mao’.

That’s why, under the right-wing regime of the National Party, the IRR was denounced as left-wing, and now, under the left-wing regime of the African National Congress, the IRR is denounced as right-wing.

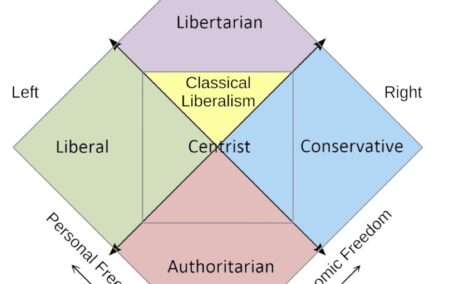

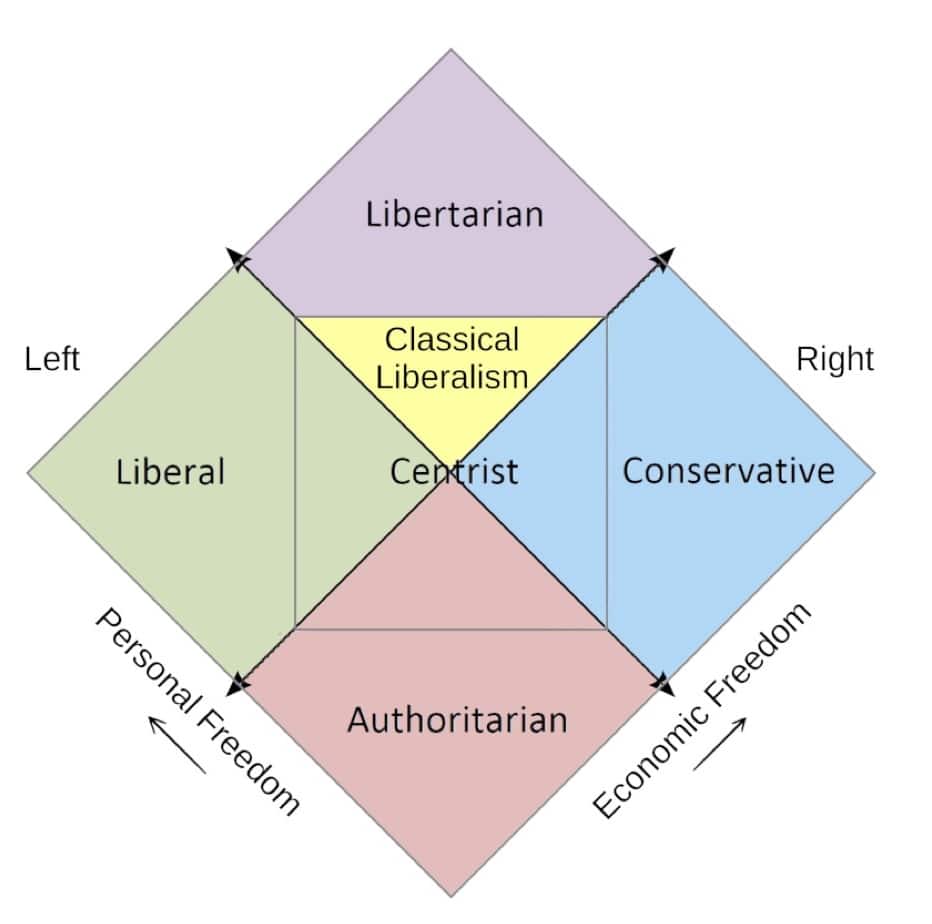

In reality, classical liberalism more closely resembles a position of radical centrism. It is idealistic in its belief in liberty, but realistic and pragmatic in its policy positions. It sometimes shares views with the right, and sometimes shares views with the left, but it cannot itself be caricatured as either right or left.

My personal views are more libertarian than those of your average classical liberal, but much the same observations are true for libertarianism: it isn’t so much a left or right position as it is a position against statism and in favour of economic and political liberty.

A Nolan Chart has internal inconsistencies that make it a poor tool for political analysis, but it beats a simplistic left-right distinction and does offer a useful conceptual shorthand:

The right sees classical liberalism as irretrievably left-wing, just as the left is trying to paint it as hopelessly right-wing. I get called socialist, woke, or totalitarian almost as often as I get called racist, reactionary, or alt-right.

Neither view holds much water. Classically liberal values are tried, true and tested, and stand on their own merits. In communism and fascism they have triumphed over both left-wing totalitarianism and right-wing totalitarianism in the past. They now appear likely to have to do so again.

Today, the enemies are illiberal left-wing populists, race-baiters, eco-socialists and anti-capitalists on one side, and equally illiberal right-wing populists, nationalists, bigots and theocrats on the other.

Classical liberals have, argues The Economist, become complacent. They underestimate their enemies on the left and the right.

‘Yet’, they write, ‘it is precisely by countering the forces propelling people to the extremes that classical liberals prevent the extremes from strengthening. By applying liberal principles, they help solve society’s many problems without anyone resorting to coercion. Only liberals appreciate diversity in all its forms and understand how to make it a strength. Only they can deal fairly with everything from education to planning and foreign policy so as to release people’s creative energies. Classical liberals must rediscover their fighting spirit. They should take on the bullies and cancellers. Liberalism is still the best engine for equitable progress. Liberals must have the courage to say so.’

I couldn’t have said it better.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend