This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

30th June 1651 – The Deluge: Khmelnytsky Uprising – The Battle of Berestechko ends with a Polish victory

Polish history is filled with many dark chapters, from the partition of Poland at the start of the 19th century to the Soviet invasion of the 1920s, and the Holocaust and the Second World War. However, in the sheer percentage of lives lost, no period of Polish history compares to the horror that was the Deluge.

The Deluge was a period between 1648 and 1666 of invasion and chaos, when the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth was invaded by Sweden, Russia, Transylvania, the German state of Brandenburg, and the Tartars of Crimea, and faced rebellions by the Zaporozhian Cossacks, Lithuanians and the Duchy of Prussia.

According to estimates by modern historians Poland lost around a third of its population, had its economy destroyed and had 188 of its towns and cities effectively destroyed.

While the most dramatic and destructive part of the Deluge was the Swedish invasion in 1655, the incident that triggered the Deluge was the rebellion by the Zaporozhian Cossacks led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky, which began in 1648.

First, it’s worth quickly going over what a Cossack is.

A Cossack is not easily defined. In the narrow sense, the Cossacks were a body of professional soldiers who fought for the eastern European powers of Poland-Lithuania and Russia and were granted a large degree of independence and autonomy. In a broader sense, Cossacks were a unique hybrid ethnic group of semi-nomadic and highly militarised Orthodox Christians, who lived on the border lands between the settled peoples of Eastern Europe and the wild grasslands of the Eurasian Steppe where the Islamic Tartars of the steppe dwelt.

The Cossacks emerged as a mixture between frontier soldiers, Christianised Tartars, Turks and Ukrainian, Romanian, as well as Russian serfs who had fled the oppressive rule of the nobility in Eastern Europe to live out on the steppe, a very wild and untamed region where violence and herding were the prime activities.

The Cossacks developed a unique culture which blended aspects of the nomadic lifestyle and dress with Orthodox Christian tradition and Slavic culture. They were also tough, fiercely independent and skilled at warfare and raiding, fighting both as excellent horsemen and infantry. They also developed a strongly democratic form of self-governance, which set the Cossacks apart from the peoples around them.

The powerful kings and feudal lords of Russia and Poland got the Cossacks to swear nominal allegiance to them but in practice allowed the Cossacks a wide degree of autonomy to rule themselves, because they acted as a buffer against the constant slave raids by the Tartars of the Steppe who were always seeking out new slaves for the Turkish slave markets of Constantinople.

By the 1600s, the Polish kings had established a ‘Cossack register’ to more formally manage the Cossacks. Registered Cossacks were the officer class of the Cossacks, officially paid by the Polish king and granted exemptions from taxes as well as special rights and privileges which put them apart from ordinary Cossacks and the serfs which worked the fields and were almost the property of their lords.

By the 1640s tensions between the powerful Polish and Ukrainian nobility and the Cossacks had been growing for some time. The Tartars were not the menace they once were, and the nobles continually sought to subjugate the non-registered Cossacks and turn them into serfs to work the Commonwealth’s highly productive farm estates.

The Cossacks for their part sought expansions of the Cossack register to enhance their pay and privileges as well as protect them from the nobles. As registered Cossacks could not be made serfs, they also were disliked by the Commonwealth’s nobles, as in the frequent clashes between the king and the nobles, the Cossacks usually supported the monarch. Furthermore, the Cossacks had come under some pressure by the mostly Catholic nobility to convert to Catholicism. At the same time, the relatively generous rights given to Jews by the Poles caused resentment among the Cossacks and the serfs who did not like Jewish managers and landlords ruling over ‘good Christians’.

The Cossacks also were always excited for war with the Ottoman Empire, as it was through war against the ‘infidels’ that the Cossacks accumulated much of their wealth, by plunder. The nobles however disliked war as it was expensive and invariably saw their estates damaged and so often used their power in the Polish Parliament, the Sejm, to block the king’s war plans. In 1647, the Sejm blocked a plan to attack the Ottomans, and this outraged the Cossacks.

In 1648 these tensions came to a head when the Ukranian noble, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, who had a Cossack mother and had a bad falling out with the authorities, was elected Hetman or leader of the Cossacks and subsequently issued a demand that the king of the commonwealth increase the size of the Cossack register. This was denied, and so the Cossacks launched an uprising.

They quickly allied with Ukrainian serfs and their old enemies the Crimean Tartars and began to ravage the countryside, carrying out massacres of Jews and Catholic clergy. Chaos reigned across the Ukrainian lands of the Commonwealth, and the Polish army was unable to crush the rebels. Khmelnytsky realized that his rebellion might see him become ruler of an independent Ukrainian kingdom and his demands expanded to that of autonomy for Ukraine.

In 1649 the Cossacks fought the Poles to a standstill and signed the Treaty of Zboriv, which expanded the Cossack register and essentially created an autonomous Cossack state within the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, banning Jewish residence in the new state.

While initially accepted, this treaty collapsed when the Polish Catholic bishops refused to agree, as they wanted revenge for the slaughter of so many priests.

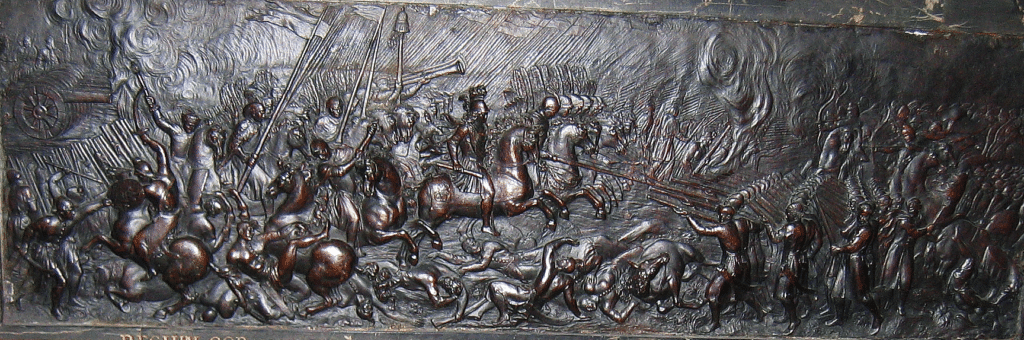

Hostilities resumed and on 28 June 1651, a Cossack, Tartar and peasant army of around 200 000 faced off against a Polish army of 80 000 at the Battle of Berestechko. After three days of fighting, during which the Cossacks resisted Polish cavalry charges against their wagon forts, the Polish horsemen broke the Cossacks and destroyed their army.

However, the Poles failed to follow up their victory with pursuit, and so Khmelnytsky would live to fight another day. Khmelnytsky would continue to fight the Poles until his death in 1657.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend