This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

21st July 356 BC – The Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, one of the Seven Wonders of the World, is destroyed by arson

The Greek world of ancient times was not quite what the Greek world is in our age. Today the vast majority of Greeks live in Greece and Cyprus and the United States, with major communities scattered around the world from Germany to South Africa to Ukraine.

However, in the time before the modern world, many of the Greek people lived along the western coast of Anatolia in what is today Turkey. Greeks were a majority, or a significant minority, in these regions until the 20th century, when in the aftermath of the Greco-Turkish War the two sides forcibly swopped their populations, destroying the Greek communities in Turkey and the Turkish communities in Greece.

Much of Greek cultural history is still to be found in western Turkey, as evidenced by the numerous ruins on the Anatolian coast.

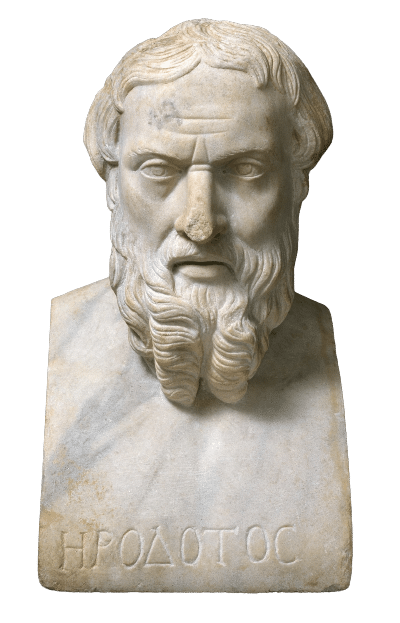

Some of the greatest figures in Greek history, such as Herodotus, the ‘Father of History’, were from places like Halicarnassus, a Greek city on the Anatolian coast. Halicarnassus was also home to one of the seven wonders of the world, the great Mausoleum.

Just north of Halicarnassus, was a Greek city by the name of Ephesus, close to the modern-day Turkish city of Selçuk.

Ephesus, has been inhabited by human beings since around the year 6000 BC. It first became Greek somewhere around the 1200s BC when the Bronze Age people, the Mycenaeans (who would become the Greeks) first settled in the area.

The official founding of the city by the Greeks was in the 10th century BC when Ionian Greeks from Attica, supposedly led by a prince of Athens, established the town on the instructions of the Oracle at Delphi, who had said to the prince: ‘A fish and a boar will show you the way.’

The Greek settlers – even in their own history of the city – talked of integrating many of the local Anatolian peoples, the Carians and Lelegians, into their settlement.

The two cultures quickly blended, with the local Anatolian goddess Kybele and the Greek goddess Artemis being associated as one and the same. It was this goddess – as the boar was a sacred animal to her – who became the chief deity of the city.

As was tradition in the Greek world, the city constructed a large temple to Artemis, sometime between its founding and the 650s BC. This first Temple of Artemis was burned down and destroyed when Cimmerians from southern Russia and Ukraine migrated into Anatolia and clashed with the people of Ephesus.

In 560 BC the city was conquered by the expanding Anatolian kingdom of Lydia and their king Croesus, who – after securing the submission of the city – spent considerable resources on constructing the mighty Temple of Artemis, which would become legendary across the Greek world.

The new Lydian-funded temple was built under the direction of a famous Cretan architect, called Chersiphron. This new building was 115 metres long, 46 metres wide and in some places was over 13 metres high. It was constructed mostly of marble; according to some, it was the first Greek temple to be built of marble.

Later Greek writers in the 2nd Century BC writing guidebooks for tourists would list the temple as one of the ‘Seven wonders of the world’ and a must-see sight for any who had the chance to do so.

According to ancient Greek historians, this second version of the temple was burned down on 21 July 356 BC by an arsonist, Herostratus, who apparently committed the arson as he sought fame by any means, even by way of infamy. It is from him that we get the phrase Herostratic fame, which is fame sought at any cost.

Herostratus was executed by the Ephesians and they forbade anyone from writing or mentioning his name. As we know his name, clearly this law was not followed.

Modern historians have cast doubt on the arson story. Some have even suggested an inside job by the priesthood, as part of efforts to get the temple moved due to problems with flooding that the temple routinely experienced. Temples were very sacred structures, and one couldn’t simply move them without triggering a significant backlash. Herostratus also apparently only confessed during torture, which does not seem the behaviour of someone only seeking fame. Some scholars have even suggested that he was an unwitting pawn of the priests.

The temple would be in ruins until 323 BC when the Ephesians rebuilt it for the final time, at their own expense. It was slightly larger than the second version.

This third version of the temple stood until at least 268 AD, when a Gothic raid sacked the city. However, this is not entirely clear, and the temple may have still been in use or left standing for some time yet. The temple definitively fell out of use in the 5th century as the Roman Empire turned towards Christianity and shut down most of the old pagan temples. Over the following centuries parts of the temple were used in the construction of other buildings by local people.

Ephesus would continue to be a major city of the Eastern Roman Empire, but slowly began to decline in the 600s. Silting up of the harbour cut off its access to the sea. This was made worse by an earthquake in 614, and sacks by Arab raiders in the year 654.

When the Turks conquered Ephesus in 1090 it was but a small village.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend