The reasons for hope for the future are dimming, and it’s not because of climate change, or running out of resources, or any of the fashionable doom-laden theories.

Normally, my first column of every year is a reminder – to myself as much as my readers – that in the big scheme of things, the world is a better place now than it has ever been before.

It has long been impossible to sustain that optimism on a short-term, South African level, thanks to the extraordinary failure of the ANC to even try to provide a better life for all.

I expect load-shedding to get worse. I expect business conditions to get worse. I expect the middle class to shrink. I expect the rich to flee the country. I expect poverty and unemployment to continue rising.

I expect nothing good in South Africa in the foreseeable future, and it would take an improbably popular and successful new government to pick up the pieces and spark a rise from the ashes of decades of ANC misrule.

Still, at least the broader global trends have always pointed largely in the right direction.

However, I can’t avoid the feeling that the world, too, has lately been headed in the wrong direction.

Best of times

Despite everything, we’re still living in what are mostly the best of times, of course. This article by the great Marian L. Tupy, editor of Human Progress, is the sort of piece that I might have written, and I agree with the premise: human intellect is the superabundant resource on which recent centuries of remarkable progress have been built, and there is no reason to start betting against it now.

Human Progress has the stats to back it up:

‘In 1950, the average life expectancy at birth was only 48,5 years. In 2019, it was 72,8 years. That’s an increase of 50%.

‘Out of every 1 000 live births in 1950, 20,6 children died before their fifth birthday. That number was only 2,7 in 2019. That’s a reduction of 87 percent.

‘Between 1950 and 2018, the average income per person rose from $3 296 to $15 138. That’s an inflation-adjusted increase of 359 percent.

‘Between 1961 and 2013, the average food supply per person per day rose from 2 191 calories to 2 885 calories. That’s an increase of 31,7 percent.

‘In 1950, the length of schooling that a person could typically expect to receive was 2,59 years. In 2017, it was 8 years. That’s a 209 percent increase.

‘The world’s democratic score rose from an average of 5,31 out of 10 in 1950 to an average of 7,21 out of 10 in 2017. That’s a 35,8 percent increase.’

Extreme poverty

The global extreme poverty rate, one of the most important indicators of the success of free-market capitalism, declined from 38% in 1990 to 8.4% in 2019. Even in sub-Saharan Africa, it improved, from over 50% in 1990 to about 35% in 2019.

Catastrophic pandemic lockdowns, which destroyed lives and livelihoods, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine have reversed this all-important trend, but ultimately, these are short-term blips in a longer history of poverty alleviation, and the World Bank expects extreme poverty to reach a record low of about 7% of the global population by 2030.

My concern isn’t so much about short-term setbacks as it is about longer-term trends.

A lot of the chickens that critics of the 20th century’s Keynesian economics have been warning about for years appear to be coming home to roost.

Reckless inflation of the money supply to fund deficit spending has caused price inflation to spill over from the usual asset bubbles to consumer prices, which around the world have reached levels not seen in over a generation.

The world is facing what might be years of stagflation, and on both sides of the Atlantic, the absurd policy prescription to ‘fight inflation’ is to print more money, to spend more on infrastructure, and even to give struggling consumers more cash payments.

Parrot

It’s as if politicians have never taken an Economics 101 class. Wait, of course they haven’t. But, as the Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher Thomas Carlyle once quipped: ‘Teach a parrot the terms supply and demand and you’ve got an economist.’

Surely the average finance minister should know that if you increase the supply of money in a market without a commensurate increase in the quantity of goods and services available, the only possible result is further price inflation.

How can they, in good faith, call a spending-and-subsidy law ‘The Inflation Reduction Act’?

The growth of government in the rich world has for decades put a damper on economic growth. Cronyism has enriched big business at the expense of both consumers and smaller competitors. Money printing has transferred trillions from the poor to the rich.

None of these are features of true free-market capitalism. All of these are features of governments that are too powerful. However, the media has done a very poor job of making this clear to the people suffering the ill effects of government policy that protected the rich and big business at their expense.

As a result, I fear that unfree societies are growing more powerful and more admired, and that free societies are growing less free. Politics on both sides of the aisle are descending into toxic populism, intolerance, and outright fascism.

Idealism

Perhaps the most worrying fact is that while it is natural for young people to be attracted to socialism for its apparently noble, egalitarian ideals, people have always tended to outgrow this youthful and misplaced idealism – until now.

There’s a new generation of young adults who have not seen the catastrophic experiments with socialism of the 20th century. They have not seen the totalitarian loss of freedom and death that socialism produced. They have not seen the Gulags, or the Cambodian terror, or the polluted industrial wastelands of Europe behind the Iron Curtain. They probably don’t even know what the Iron Curtain was, nor have they read Solzhenitsyn or watched The Killing Fields.

They have not seen the poverty, drudgery and hunger in the Soviet Union, and its ultimate collapse. They have not seen countries with borders designed to keep people in, rather than out.

They think of modern-day examples like Zimbabwe, North Korea and Venezuela as simply isolated anomalies probably caused by Western imperialism or some such evil.

Whenever they see a problem in the world, their response is ‘the government must do something’. Whenever they see financial hardship, they say ‘government should tax the rich to make it better’. Whenever they see corporate welfare, they blame capitalism. Whenever they see challenges in their own lives, they think ‘government should help’.

And politicians, craven and self-serving as they are, fall over themselves to promise more ‘free’ stuff than their rivals.

Socialist by 20, capitalist by 40

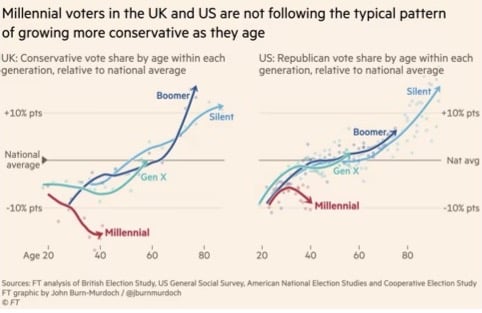

On both sides of the Atlantic, according to the Financial Times (paywalled), the millennial generation swings left, but then instead of recovering their senses, they continue to move even further left as they approach 40:

That one has no heart if one isn’t a socialist at 20, and no brain if one isn’t a capitalist at 40, is a maxim that has held true for a century, but millennials are breaking the mould.

The innovation and ingenuity of free people operating in a capitalist market without undue government interference is the reason why virtually all indicators of human welfare have improved dramatically since the 19th century.

Governments have played a supporting role by providing stable institutions and reliable means of protecting individual rights and enforcing contracts.

It isn’t clear to me that improving working conditions and a social safety net required the intervention of the state, but let’s be generous and credit at least some of those gains to the enlightened intervention of liberal democratic governments.

The belief that those improving trends in living standards would naturally continue is premised on the belief that liberal democracy and free enterprise can survive. There are more reasons than ever to doubt that.

Change

This year, we all need to redouble our efforts to explain the evils not only of socialism, but also of state-capitalism, cronyism, big government and inflationary monetary policy.

It is more important than ever to promote the ideals of free enterprise and individual rights and liberties as the only sustainable political solution to the modern world’s real and immediate problems.

Most importantly, the virtues of classical liberalism need to be sold to Millennials and Generation Z, since they are the generations threatening to plunge the world into another generation or two of socialist privation.

When they complain about some modern ill, like student debt, the unaffordability of housing, the rising cost of healthcare, or food price inflation, it needs to be explained clearly how and why government intervention and a lack of freedom – as opposed to the greed of the rich or the capitalist system – lie at the root of the problem.

People will always grasp for some amorphous notion of ‘change’ when they’re dissatisfied with the present. It is more important than ever that ‘change’ should come to mean smaller government, less economic intervention and more vibrant free markets, rather than the road to serfdom that is big-government socialism.

This is why my assessment not just of South Africa’s future, but the future of the world, has grown bleak of late.

Anyway, Happy New Year. My wish for 2023 is that it won’t be that much worse than 2022.

[Image: Egor Myznik for unsplash]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend