An economic crisis that began under Hugo Chávez has accelerated under Nicolás Maduro.

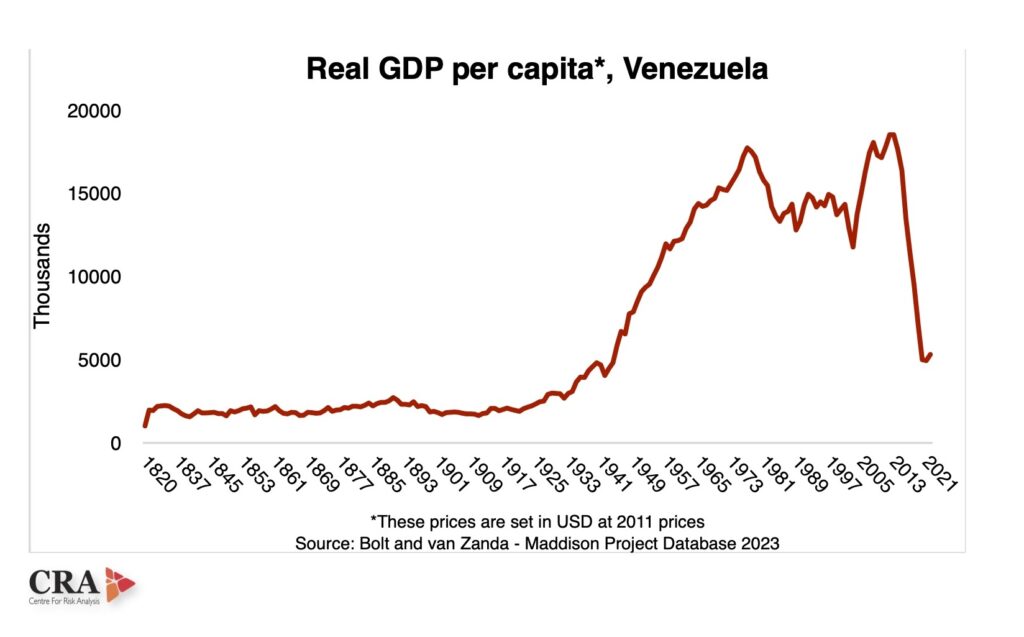

From 2013 to 2021, 7 million Venezuelans (about a quarter of the population) fled the country. The annual rate of inflation averaged over 9000% from 2012 to 2022, cooling to a mere 50% over the course of last year. In 2018, real GDP per capita was at a level last seen during World War II; it has barely edged back upward since.

This is the setting in which Venezuelans headed to the polls late last month, and in which the Maduro-controlled National Electoral Council (CNE) declared him the winner with 51% of the vote, giving his main opponent, Edmundo González, 44%. However, tally slips which the opposition collected from 79% of the voting stations in the country show that González in fact received twice as many votes as Maduro. That would put the actual result closer to 66% for González versus 31% for Maduro.

Political scientist Steven Levitsky called the official results “one of the most egregious electoral frauds in modern Latin American history”. Protests which erupted shortly after the election have continued, with human rights NGO Foro Penal reporting that at least 11 people (two of whom were minors) were killed in the first week of protests. According to the authorities at least 177 people had been arrested; the actual number is likely much higher.

Over a week after the vote, the CNE has yet to make available voting-station results to be audited, as required by Venezuelan law. The Maduro administration has detained opposition politicians and announced criminal probes against opposition leaders. World leaders have predominantly rejected the CNE’s claimed results, although some countries have recognised Maduro’s “victory”, among them China, Cuba, Iran, North Korea, and Russia.

Venezuela’s current political turmoil is closely linked to its long-standing economic crisis.

In part, the country’s economic fortunes rise and fall with the price of oil. In 2014 the international oil price stood at over $100 per barrel; by early 2016 it had dropped to below $30 per barrel. This was not within the Venezuelan government’s power to control; however, its domestic policies very much were.

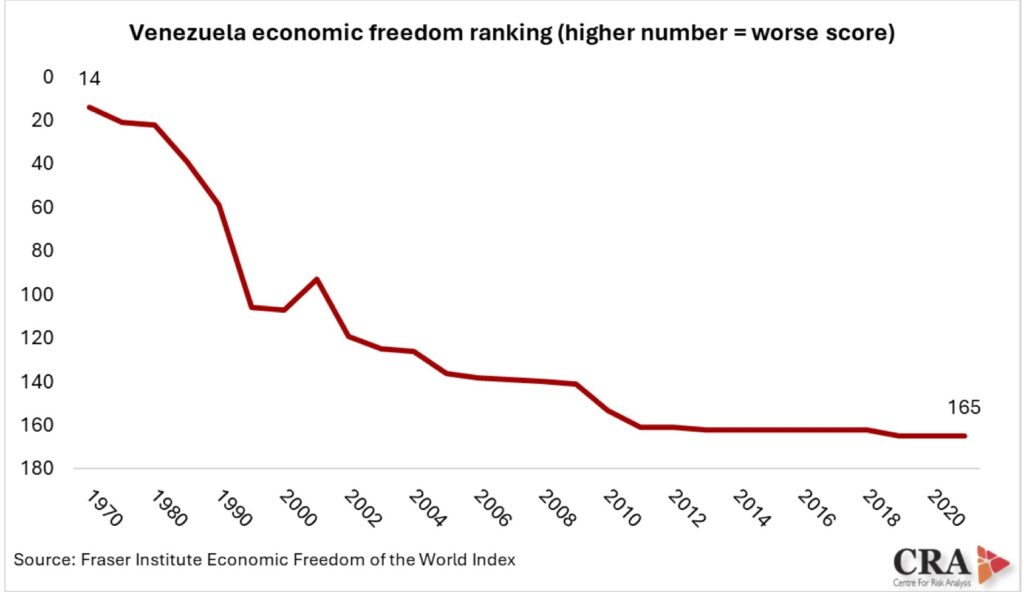

Hugo Chávez, who benefitted from high oil prices during most of his presidency, sought to introduce “socialism of the 21st century”, a form of revisionist Marxism, in Venezuela. Political repression and the manipulation of elections became the order of the day. Property rights were undermined and the price mechanism was manipulated through price controls. Companies in the steel, agriculture, mining, and transportation sectors were expropriated, as were many farms. It was no surprise that “the people’s wealth” did not trickle down.

When running a socialist government, it is one thing to benefit from global tailwinds, such as higher oil prices in Venezuela’s case. It becomes another matter entirely when the wishes of the government clash with economic reality.

Expropriation of property, price controls, and other aggressive forms of state intervention in an economy are what typically produce “a small state-connected minority controlling much of the nation’s wealth.” It is not, as economists interviewed by the New York Times would have it, “brutal capitalism”.

When a country’s level of economic freedom declines – expressed in policy choices that favour increasing state control over the economy and society – the incentives for corruption and suppression of political competition only multiply.

To be sure, more economic freedom is no guarantee of prosperity, but it makes economic growth and progress far more likely. What matters most is liberty, and the degree to which it is protected rather than infringed upon. It just so happens that countries that respect and strengthen liberty tend to deliver better quality of life for the people who live there, while those that pursue policies inspired by the teachings of Karl Marx inevitably do worse.

South Africa is no exception to the rules of economics, and indeed the rules and requirements of prosperity.

Material prosperity is not a given, something to be randomly stumbled upon. It is the result of making the right choices and taking the right actions. Economic activity, capital formation and investment, infrastructure builds, and delivery of services to citizens: these contributors to growth and prosperity need to be encouraged.

The brave people of Venezuela, their lives wrecked by Chávez and then Maduro, have taken to the streets with the hope that their country can be turned around. With every subverted election, and every dictator clinging to power, the feat becomes just that much more difficult to pull off.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.

To learn more about a CRA premium subscription, contact sherwin@cra-sa.com