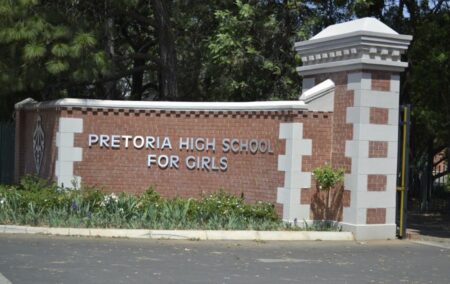

Twelve 12th grade pupils at Pretoria High School for Girls (PHSG) recently went through a public ordeal involving government officials, political parties, and the press media. They were accused of engaging in racism. Guilty or not, as a society we need to ask: why do we regard our children as legitimate items of political contestation?

If the twelve girls were found to be racist, they should at least have been disciplined, and more likely have been suspended and ultimately expelled. The school was right to investigate the allegations.

In this context, they were however found to be not guilty. This has not satisfied the bloodhounds, for whom only a guilty verdict would be a legitimate outcome. Therefore, the Gauteng Department of Education, which Panyaza Lesufi turned into a race-obsessed circus, will conduct its own ‘investigation.’

But the discrete allegation of racism is the less important aspect of this debacle. Even if the girls were racist, they should have been protected – first and foremost by their parents, and second by the school – from the political circus that followed.

Expelling them, quietly, for actual misbehaviour, is an appropriate remedy. Traumatising them in full view of the world is not.

Kids, often, are stupid – and perhaps even evil. But childhood is the time in our lives when we get to be stupid and evil, and discover the true meaning and implication of ‘consequences’. Children and teenagers should be allowed to be stupid and evil in relative safety, provided they do not cause real, quantifiable harm to the interests of others.

This safety should be guaranteed, under all circumstances, by their parents and daytime guardians at school.

This applies just as much to the dreadful girl who recorded herself saying her white peers should ‘bow’ before her, as it does to the other twelve girls.

Devastate those who seek to politicise children

If there is even the slightest hint that a political issue will be made of pupils, whose whole life awaiting them might be ruined, the parents must stop whatever else it is they are doing – their careers, hobbies, or further education – and bring absolute and uncompromising devastation to whoever initiated or enabled the politicisation.

They must start, of course, with the school.

Parents are forced, by law, to enrol their children in schools. There is no legal choice. In other words, parents are forced to part with their supervision of their kids for at least six hours of five days out of every week. Again – and this cannot be over-emphasised – there is no choice in this.

And because there is no choice, the school enters into a sacred pact with the parents: We will safeguard the interests of your children, who we take from you by force, with every fibre of our being. In all circumstances, the interests of your children will weigh more heavily than our own interests.

If the school fails to live up to this sacred pact, parents must exact a very costly vengeance. Even if the school did not instigate the trouble, it was the school’s sacred responsibility to shield its wards from the political abuse that followed. The school does not get to shift responsibility to the education department or even to the law. The school is where the rubber meets the road.

Agency and choice

While the girls in question are somewhere between 17 and 19, age is not entirely relevant in this context. Choice is relevant.

School is not a choice. Placing a bunch of kids and adults together in a situation that is necessarily characterised by coerced association means that different rules from what we expect in ordinary society do and must apply.

The kids, who are forced to be present, are not full agents, even if they are over 18. Their volition is limited by law.

The reason Hamas cannot legitimately say ‘they were soldiers’ is a valid justification for kidnapping, raping, and murdering unarmed 19-year-old women in civilian clothing – they were conscripts who had no choice but to serve occasionally in the Israeli Defence Force – is the same reason we cannot expect pupils to be completely volitional agents.

One expects that were compulsory schooling laws – a relatively novel innovation – to be absent, many parents and kids would choose not to place themselves in situations where they feel discriminated against; as the girls at PHSG alleged that they were. And kids who want to wear afro-styled hair or doeks would not go to places where afro-styled hair or doeks are prohibited (because they have a choice).

But because they have no choice, we cannot – at least not fully – hold kids accountable for the things they do to adapt to the involuntary situation they find themselves in. We certainly cannot ruin their lives for a ‘choice’ they made within the context of being forced into association with others.

The answer is known: We are abdicating responsibility

Of course, we already know the answer to the question I am posing with the title of this column.

The reason children are not off the table of political contestation is because we decided, long ago – and continue affirming this decision, every day – that our children are in fact the state’s responsibility rather than our own. We are, in fact, quite happy to abandon our responsibility for our children.

Only when this begins to sit uneasily with us can we start truly building the framework necessary to protect children from the increasingly abusive and all-encompassing realm of politics. And what begins as an unease must necessarily end with the abolition of compulsory schooling laws, the privatisation of public education, and restoring respect for the principle of freedom of association.

We all have a role to play in this endeavour, but for once it is not the job of think tanks, politicians, or officials to lead the charge. It is the sacred responsibility of parents qua parents.

[Photo: FaceBook]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend.