The South African Constitution’s clearly stated section 11: “Everyone has the right to life” should be carefully reviewed and, in my view, changed to read: “Everyone has the right to life, except those who take a life.”

My reasoning is straightforward: if someone is determined to end another’s life, why should their own life be spared? Particularly when the person taking the life of another is perfectly OK mentally, and it defies sense for them to take another person’s life.

It makes sense for someone at risk of losing their life to take the life of the person threatening them in order to protect themselves. However, it defies logic that our laws permit people who deliberately take another person’s life to live on after doing so, leaving the victim’s family devastated and traumatised for the rest of their lives.

As an instance, cash-in-transit heists are on the rise in our society, and criminals who plan and carry out these thefts have a specific goal in mind: to kill cash-in-transit truck drivers as well as any security guards assigned to watch over the money-laden vehicles.

We should be enraged that such criminals are allowed to continue living when their victims perish and their families suffer terrible wounds. These thugs kill people on purpose and knowingly in order to obtain money that they invariably spend ostentatiously on cars, designer clothing, alcohol, and other gaudy displays.

Another example is the horrifying phrase that is all too common in many of our townships, when a thug says to a victim, “Ke tla go pantitela tsotsi!” (“I will only go to prison for killing you!”). This is a common phrase when someone is robbing you. If you refuse to hand over your valuables to them, you can be confident that they will likely only “go to prison for killing you”, and soon come back to enjoy their life while you are dead.

In townships, people can lose their lives for the smallest things. In 2015, I nearly lost my life to a bunch of hoodlums in the Joza township in Grahamstown (now known as Makhanda) in the Eastern Cape, at a chilling spot called Kwa-Mandisa.

As student at Rhodes University, my friends and I had gone from downtown Grahamstown to the township. Our group included some really attractive females. Two of them caught the attention of another man, who expressed some interest in them. As they were not interested in him, both pretended to be my girlfriends, hoping he would lose interest.

I didn’t think anything of it, but out of the blue, as we leaving Kwa-Mandisa, I heard a friend of mine, Solomzi “Sol” Thabatha, scream: “Thotse, Thotse mchana! Bayeza! Baleka!” (“Thotse, Thotse my friend! They are coming! Run!”) (Solomzi is regrettably no longer with us; he was murdered on 16 December 2019, in Eastern Cape’s Queenstown township, over a silly argument with some fool).

As I turned to see what Sol was screaming about, I saw a gang of guys with knives charging towards me. One of them was the man who’d expressed an interest in the girls earlier on. I fled. Being asthmatic, I eventually ran out of breath and was unable to run very far. Fortunately, I had managed to turn into a lane without my pursuers spotting me. I ducked behind a tree, and the group soon passed by, running past my hiding place. Once they had done so, I leaped over the fence of a nearby house and hid there for almost two hours until I was pretty sure the thugs had given up looking for me. Nobody was in the house or yard. When I eventually made my way back to the city, I went straight to the police station.

I informed the officers on duty what had occurred. The police told me that my friends had reported the matter earlier but that as there had been no vehicles they hadn’t been to do anything to help.

I am fortunate to be alive. That incident could very well have been the end of me. And over what? Something so incredibly foolish! If those young men had been able to catch and kill me, should they have been allowed to live? What about my family? What about my future, that I’d have been robbed of, my dreams and aspirations, and the dreams and aspirations that my family and friends had for me? What about all of that?

It is insane that someone can choose to take all these things from someone for no apparent reason and yet still get to live, just as in my late friend Sol’s instance. Surely, we are not thinking clearly by not returning the death penalty to the statute book. Logic dictates that if someone who is fully functioning mentally decides to deliberately take the life of another while not acting in self-defence, he should be eliminated as well.

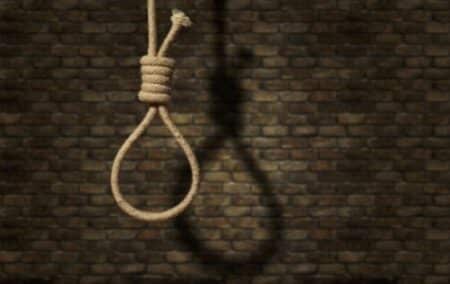

As a result, I wholeheartedly endorse Correctional Services Minister Pieter Groenewald’s suggestion that the death sentence be reintroduced. Strict, rational laws should be enacted to determine where the death penalty should be used and where it should not. In cases where someone murders someone who is not a threat to their life in front of an audience, in full view of cameras, or in such plain and unequivocal cases, those who kill must undoubtedly be slain as well.

Two common arguments against the reinstatement of the death penalty are:

1. That there is insufficient evidence, in countries where death penalty laws are in place, that they reduce homicide rates.

2. That, the death penalty as a statute would not work well in our country’s current environment, given that corruption is rampant in our society and innocent people will die as a result of bribes paid to the South African Police Services (SAPS) murder investigators to tamper with evidence and members of our judiciary.

To answer briefly to the arguments:

1. While it would be wonderful if the reintroduction of death penalty laws could help reduce our country’s high murder rate, the concern is not only about attempting to reduce the murder rate, but also about providing true justice to the families and loved ones whose loved ones’ lives are taken by people who currently continue to enjoy their own lives.

To take the life of another and carry on living your own is incomprehensible. Actions taken on one hand must necessitate action on the other. To ensure that the proper people are executed, however, there should be no question as to whether they actually committed the crime. There must be unambiguous evidence. Because of this, there needs to be very strong legislation governing this.

2. As above stated, executions should only occur in situations when there is absolute proof that the accused committed murder. In this case, anyone who rules under bribery that an accused person has to be put to death, even though there is the slightest possibility that the accused did not really commit the murder, will have to be held accountable. I venture to suggest, they themselves should be put to death.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend