Market liberalism is one part of traditional liberalism which didn’t start out being about markets. Liberalism evolved over centuries of history and free markets came a bit later in the game.

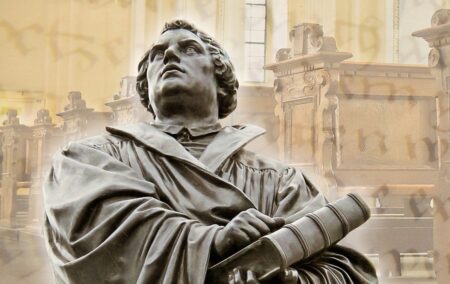

Liberalism evolved out of the religious wars where both Protestants and Catholics violently attempted to suppress beliefs they didn’t like. Martin Luther wrote, “Let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly and openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful or devilish than a rebel.” He argued the state was obligated “to repress blasphemy, false doctrine and heresy, and to inflict corporal punishment on those that support such things.”

Of course, what was true for Luther was true for the Vatican, Calvin, and other reformationists as well. The results were a couple centuries of mass genocide as each faith attempted to wipe out competitors. In total these religious wars killed more than Hitler’s genocide resulting some 7 to 11.5 million being killed.

Professor Perez Zagorian, in How the Idea of Religious Toleration Came to the West said no major faith was exempt, “None of the Protestant churches — neither the Lutheran Evangelical, The Zwinglian, the Calvinist Reformed nor the Anglican — were tolerant or acknowledged any freedom to dissent.”

England’s Catholic Queen Mary had some 300 Protestants burned at the stake and French Catholics massacred some 5,000 to 30,000 Protestants. Out of this astounding violence and genocide rose the idea of religious freedom. From that principle came support for freedom of thought in general, even for the non-religious. People simply grew tired of the killings and the poverty resulting from it.

Individual thought

One result was the rise in religious sects and with each new sect the powers of a dominant sect declined. This weakening meant less ability to impose controls on individual thought. Voltaire explained this process in 1734, “If one religion only were allowed in England, the Government would very possibly become arbitrary; if there were but two, the people would cut one another’s throats; but as there are such a multitude, they all live happy and in peace.”

Out of these newfound freedoms a fuller version of liberalism eventually evolved. Liberalism saw the connection between freedom of thought and free markets. Sir Samuel Brittan wrote, “The breakdown of theological authority, the rise of scientific spirit and the growth of capitalism were inter-related phenomena.”

Freedom of thought meant freedom of action which resulted in the evolution of market economies where production and mutual trade became more important. Seeing others as trading partners and not enemies was an important factor for markets. Importantly this greater market freedom reinforced free thought as well. Merchants found the most beneficial trade they could make was often with someone of a different faith or creed. Refusal to trade with them meant lost opportunities and foregone profits.

Voltaire again described this:

“Take a view of the Royal Exchange in London, a place more venerable than many courts of justice, where the representatives of all nations meet for the benefit of mankind. There the Jew, the Mahometan [Muslim], and the Christian transact together, as though they all professed the same religion, and give the name of infidel to none but bankrupts. There the Presbyterian confides in the Anabaptist, and the Churchman depends on the Quaker’s word.”

Prejudicial policies

Businessmen, who rely on voluntary exchange, have long been leaders of movements that undermine traditional prejudices. People who trade want more trading options, not less, and prejudicial policies limit the number of options. Henry Kamen, in The Rise of Toleration [McGraw Hill, 1967], wrote:

“The expansion of commercial capitalism, particularly in Europe’s two principal maritime powers, Holland and England, was a powerful factor in the destruction of religious restrictions. Trade was usually a stronger argument than religion. Catholic Venice in the sixteenth century was reluctant to close its ports to the ships of the Lutheran Hanseatic traders. The English wool interest spent the first half of the seventeenth century in energetic opposition to the anti-Spanish policy of the government. By the Restoration in 1660 it was widely held that trade knows no religious barriers; the important corollary that followed from this was that the abolition of religious barriers would promote trade.”

Sir Willian Petty in his Political Arithmetic from 1670 wrote: “For the advancement of trade… indulgence must be granted in matters of opinion.” Samuel Parker’s A Discourse on Ecclesiastical Politie [1669], said “tis notorious that there is not any sort of people so inclinable to seditious practices as the trading part of a nation.” The chaplain to the Earl of Berkeley complained, “that the great outcry for liberty of trade is near of kin to that of liberty of conscience.”

The link between freedom to think and freedom of trade is strong. From free thought evolved free trade which in turn strengthened diversity of thought.

[Image: Andreas Breitling from Pixabay]

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, support the Daily Friend