This Week in History recalls memorable and decisive events and personalities of the past.

September 28th 1928 – Discovery of penicillin

On 28 September 1928, Scottish physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming returned from holiday to an intriguing discovery. He found that of three samples of Staphylococci bacteria he had left in laboratory before going away, two were as he left them, but the third had been contaminated with fungus, and that the bacteria colonies around the fungus were dead. He later recalled remarking: ‘That’s funny.’ But it soon turned out he had stumbled on the first antibiotic, a discovery that would change the lives of all humanity.

Born in 1881 on a farm in Ayrshire, Scotland, Fleming moved to London as a teenager. He worked for a few years in a shipping office until, at 24, on the advice of his brother who was already a doctor, he enrolled at the St Mary’s Hospital Medical School in Paddington, where he graduated, with distinction, with a bachelor of medicine in 1906.

Fleming was a member of the rifle club at medical school and, as he was a good shot, the captain of the club was keen to keep him on the team after his graduation, and so suggested he join the research department at St Mary’s, where he became an assistant bacteriologist to Sir Almroth Wright, a pioneer in vaccine therapy and immunology.

At the outbreak of the First World War, Fleming enlisted with the Royal Army Medical Corps, and gained extensive hands-on experience with bacterial infection and sepsis. He discovered, for instance, that the incorrect use of anti-septic actually worsened sepsis in deep wounds as it killed beneficial agents without destroying the harmful bacteria.

After the war, Fleming continued work on anti-bacterial substances, discovering in 1922 that nasal mucus inhibited bacterial growth due to an enzyme called lysozyme, which is present in many bodily secretions.

In 1927, Fleming began to study Staphylococcus bacteria whose toxins are a common cause of food poisoning. It was during this period of study, in 1928, that he made the accidental discovery that particular types of mould could kill bacteria.

After some consultation with his lab assistant and his friends, Fleming identified the mould as being of the genus Penicillium. The specific species of mould he had found would only be definitively identified in 2011.

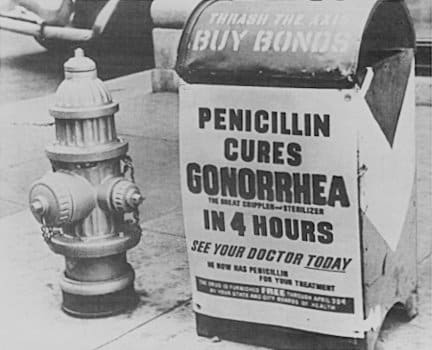

Further testing of Penicillium mould yielded the discovery that it could produce an anti-bacterial culture capable of killing the bacteria that cause scarlet fever, pneumonia, meningitis and diphtheria as well as gonorrhoea – but not typhoid fever or paratyphoid fever.

After toying with names such as ‘mould juice’ or ‘the inhibitor’, he eventually named the substance penicillin on 7 March 1929.

At first, the anti-bacterial agents proved difficult to isolate and Fleming worried that, due to the difficulty of producing the substance and because it seemed to work slowly, it would not be possible to use it as an effective medication. Early trials on penicillin were largely inconclusive; eventually Fleming abandoned his work on the substance, leaving it to two other men, Howard Florey and Ernst Boris Chain, to continue working on the substance with British and American government funding. By 1944, enough penicillin had been produced to treat all the wounded during the Allied invasion of France in the closing phase of the Second World War in Europe.

Fleming also discovered very early that bacteria developed antibiotic resistance whenever too little penicillin was used or when it was used for too short a period. He cautioned against the incorrect use of penicillin in his many speeches around the world, saying ‘the microbes are educated to resist penicillin and a host of penicillin-fast organisms is bred out … In such cases the thoughtless person playing with penicillin is morally responsible for the death of the man who finally succumbs to infection with the penicillin-resistant organism. I hope this evil can be averted.’

It is for this reason that antibiotics often require a prescription from a doctor before they are dispensed.

Penicillin would become the first antibiotic medication and would save the lives of millions of people across the world, as well as leading to the development of further antibiotics. This discovery is one of the main drivers of the enormous growth in quality of life and life expectancy across the world and has played a large role in the explosion of human flourishing since the end of the Second World War. In many ways, we owe much of what we enjoy today to the mould and its researchers.

September 29th 1911 – Italy declares war on the Ottoman Empire

In the early 20th century, Italy was a nation still hungry for imperial glory. After unification in 1861, Italian nationalists had sought to assert Italy’s place as a great power of Europe by developing its army, economy and culture, and by growing its colonial empire.

Unfortunately for the Italians, they were far behind their European rivals and struggled for much of the 19th century to catch up to France, Britain and, later, Germany. Italy had manged to snatch pieces of Africa in Eritrea and Somalia for themselves, but the nationalists demanded more. In 1894, Italy had attempted to conquer the ancient African kingdom of Ethiopia, a kingdom which had existed since 1270, and suffered a humiliating defeat against an Ethiopian army at the Battle of Adwa.

This defeat left a mark on Italian nationalism that made many Italians bitter, embarrassed and desperate to prove Italy’s strength in some other way.

During the 19th century, the Italians – through negotiations with France, Britain and Russia – had been promised a stake in the crumbling Ottoman Empire’s territory in modern-day Libya. However, they had failed to act on these claims and as such they lay dormant for the rest of the 19th century.

But when a wave of colonial favour gripped Italy in the early 20th century, some in the Italian media began lobbying in the early months of 1911 for an Italian invasion of Libya. Libya was depicted by many in the media as poorly defended by the Ottomans, rich in minerals, and with abundant water resources. It was also claimed – without much evidence – that the local population loved Italians and hated the Ottoman rulers.

The Italian government was reluctant to act on this at first, as their ally Germany was a supporter of the Ottoman Empire. However, after the French invaded Morocco and established a protectorate over the country, the Italian government began to view an invasion of Libya more favourably. Russia, France and Britain also promised to not intervene in any Italian action against the Ottomans.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire warned the Italians that attacking the Ottomans might set off a chain reaction that would destabilise the Balkans and cause an international crisis.

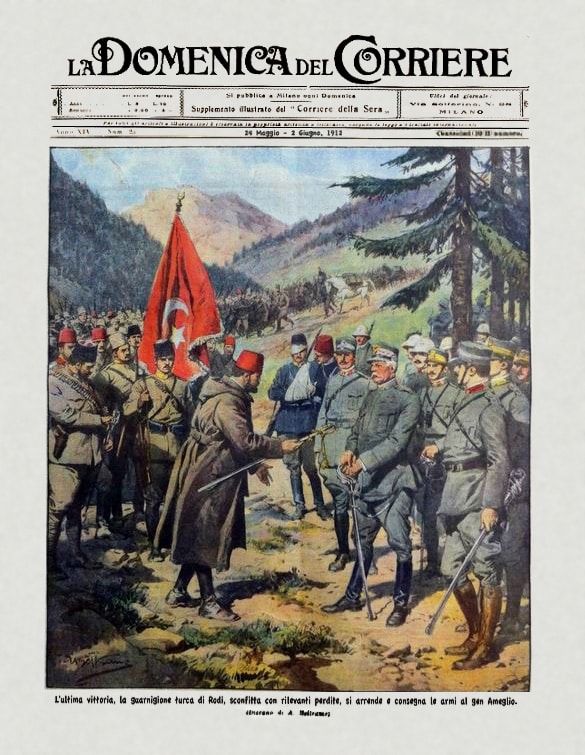

But, in September 1911, the Italian government decided to act, sending an ultimatum to the Ottomans demanding control of Libya. The Ottomans replied with a proposal to transfer control of Libya without war, maintaining a formal Ottoman suzerainty. This suggestion matched the situation in Egypt, which was under formal Ottoman suzerainty but was actually controlled by the United Kingdom. The Italians refused, perhaps because some in the government were seeking to restore national glory through war. War was declared on 29 September 1911.

The Italian army was not well prepared, and so was somewhat shambolic at the start of the war. The Ottomans, however, were even more poorly prepared, not having a proper army in Libya and being unable to send reinforcements through Egypt, as the British would not allow them through. The Ottoman navy was also too weak to contest the seas and so the Ottomans couldn’t send reinforcements be ship either. As such, the Ottomans had to organise many local Libyan tribesmen to defend the province from the Italians.

Initially, the Italians secured many of Libya’s coastal cities, but, due to Italian overconfidence, their force was small and came close to defeat several times at the hands of Arab cavalry and Ottoman troops.

Over the next few months, the Italians fortified themselves in the coastal cities and faced repeated assaults from Ottoman forces heavily supported by Muslims from modern Tunisia and Egypt, who smuggled supplies and weapons to the Ottomans. The war saw the first use in history of airplanes for scouting and for bombing, with the Italians using their air force to support their troops.

At sea, the Italians smashed the Ottoman navy and even occupied some islands in the Agean Sea off the western coast of Turkey. Both sides committed atrocities against prisoners and civilians during the war.

The Ottomans, unable to retake the coast from the Italians and unable to control the sea, agreed to peace talks. However, the weakening of the empire by the Italians, as predicted by the Austro-Hungarians, caused a shift in the balance of power, and the nations of the Balkans, which formed the Balkan League, launched an attack on the Ottomans ten days before peace was signed with the Italians. This conflict, known as the First Balkan War, would see the Ottomans almost entirely driven from Europe.

The resulting series of conflicts in the Balkans would lead to instability that would later contribute to the outbreak of the First World War.

In the peace agreement signed between Italy and the Ottomans, the Ottomans would agree to withdraw all troops from Libya in return for the Italians returning the Islands they had captured in the Agean Sea. Unfortunately for the Ottomans, subsequent conflicts and then the outbreak of the First World War saw the Italians gain control of Libya but not hand back the islands, which would eventually be given to Greece after the Second World War.

October 2nd 1552 – Russo-Kazan Wars: Russian troops enter Kazan

For centuries Russia’s princes had battled their nomadic neighbours to the east. The horse nomads and the Russians fought for control of the lucrative trade routes along the great rivers of Russia, which connected the Mediterranean with the Baltic.

The arrival of the Mongol hordes in Europe and the establishment of the Golden Horde successor state had compelled the Russian princes to pay tribute to their nomadic overlords for many centuries. During this time, one of the princes, the prince of Moscow, managed to gain the upper hand over the other Russians, by becoming the approved tax collector on behalf of their nomadic overlords.

Once they had consolidated their power, the Muscovites threw off the rule of the nomads as their empire disintegrated. Moscow then set about uniting the Russian princes under their banner and driving back the nomads. In 1547, the prince of Moscow, Ivan IV, would assume the title Tsar of Russia, founding the direct ancestor of modern Russia.

The nomads, once united under the banner of the Golden Horde, fractured as the horde grew weaker, and formed many smaller states, one of which was the khanate of Kazan, which emerged in 1438.

The territory of the Kazan Khanate lay on the confluence of the Volga and Kama River in what is today modern European Russia, consisting of many tribes of Turkic horse nomads, Finno-Ugric tribes and eastern Slavs. While some of the horse nomads remained nomadic, others settled down over the centuries to take advantage of the trade along the rivers, and the Khanate based its capital in one of these towns, Kazan, which is where the Khanate got its name.

Between the establishment of the Khanate and its destruction, the city of Kazan was besieged 10 times by the Russians; finally in 1552, the Russian Tsar, Ivan the Terrible, sent an enormous army of 150 000 to break the Khanate once and for all.

After a month-long siege – with the Russians using cannons and a ‘battery-tower’, which was a revolutionary design for a tower filled with cannons – the besiegers finally broke into the city. Tsar Ivan ordered his army to massacre the inhabitants and burn the city. Around 50 000 people were killed in the massacre that followed and almost all the buildings in the city, including its many mosques, were burned to the ground by the Russian troops.

The defeat at Kazan led to the disintegration of the Khanate’s power, and Russia began its move east in what would become its long slow conquest of the Eurasian steppe and Siberia.

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend