Enterprise and self-sufficiency are the wellspring of economic recovery, if only policy makers would see it.

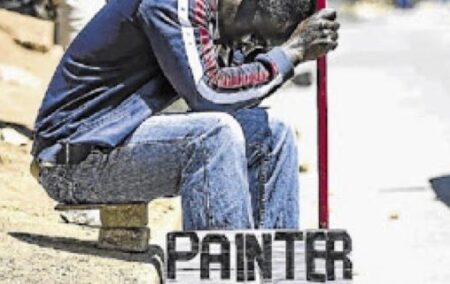

Bold, if misshapen, lettering on a crudely fashioned billboard spotted recently attracted the attention of peak-hour motorists to an offering it took a moment to decipher.

If it was obvious from the service proposition – ‘stumb removal/ruble removal’ – that the author’s entrepreneurialism did not extend to conventional standards of literacy, it was just as obvious that ingenuity doesn’t require it. Spelling hardly matters when it comes to removing a tree stump or a heap of rubble.

And far from advertising a deficiency, this signage – mounted on a trailer cheekily and conceivably illegally manhandled on to a traffic island in the middle of a busy freeway – speaks volumes for something else: enterprise and self-sufficiency.

I was reminded of this billboard in the first week of May when reading the engaging Agence France Presse report on Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) leader Julius Malema’s election campaign appearance ‘at a packed stadium in the township of Alexandra in Johannesburg’.

‘Like any crowd-puller,’ the piece began, Malema ‘knows how to build excitement: keep your audiences waiting, then tell them what they want to hear.’ After the obligatory delay, he ‘finally …appeared, emerging from a German limousine and taking a lap of honour around the venue, milking the roars of approval flooding down from the stands.’

But I was less interested in Malema and the theatre of politics he indulges in than a detail in the report about a woman sitting up in those stands who ‘lapped up’ the EFF leader’s speech, and went on to suggest why.

‘“We don’t have anything, we need jobs, we need houses, we need water, electricity, land, education,” she said. “We just want everything promised in our (post-apartheid) constitution – but nothing has changed yet.”’

The woman, who was born in the early 1970s, would have experienced the depredations of the Fortress Apartheid years, and the thrilling hope that attended the changes that began in 1990.

The promises of 1994 were, doubtless, lavish – and, many feel, remain undelivered.

But she is quite wrong in saying ‘nothing has changed’.

The democratic dividend has been immense – immeasurable in some senses, but materially measurable, too.

Our own research at the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) shows, among other things, that access to better housing, and basics such as water and electricity have soared; incomes have risen, poverty has been reduced.

In 2001, for example, nearly 40% of South Africans were estimated to live in the lower third of South Africa’s living standards spectrum. That percentage had fallen to just 10% in 2015.

The number of formal houses increased by 131% after 1996, the number of families with electricity by 192%, and the number with access to clean water by 110%.

The number of motor cars increased from 3.8 million in 1999 to 7.1 million in 2017, or by 85%. This increase reflects broadly an increase in the number of middle-class households and aligns with a series of other measures indicative of middle-class expansion.

The number of students at university has increased almost threefold since 1985, and by well over 100% since 1995. The the bulk of beneficiaries of expanding university enrolment are black, mostly from poor backgrounds where they were often the first people in their families to graduate with a university degree. In 1995, just under half the national university class was black, but by 2015 that proportion had increased to 70%.

There are many other positives.

But that woman in the stands perhaps intuitively appreciates another truth about our post-democracy trajectory.

From 2007, under Jacob Zuma’s presidency, much of the progress achieved after 1994 stalled as the governing African National Congress veered towards counterproductive policy – which deterred local and foreign investment, and made it harder for business to succeed and thus grow jobs – and resorted to racial nationalism (blaming minorities to distract attention from its own failures).

South Africa entered its longest downward business cycle since 1945. And while per capita income increased from R23 686 in 1994 to R31 460 in 2007, or by over 32%, it advanced by less than 10% over the subsequent decade.

Zuma has gone, but the policy trajectory continues to undermine growth, which means households – like that woman in the stands at Malema’s Alexandra rally – continue to feel ‘nothing has changed’.

This pessimism is widely interpreted as the cause of the low turnout in the 8 May election.

The National Association of Democratic Lawyers (Nadel) put it like this: ‘No longer do people … view the democratic electoral process as a means of delivering social and political goods….’

That seems a very worrying prospect – of either apathy or lawlessness. The former would drain the nation of vigour and enterprise. The latter might result in rules, conventions and finesse of reasoned argumentation giving way to mobs and inevitably conditions in which, as philosopher Thomas Hobbes expressed it, life would be ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’.

Certainly, the undergirding of political dysfunction, whether indifference or fury, is everywhere apparent – unemployment now at a near 15-year high (27.6%), and violent protests up since 2004 by 268%.

In a society in which political leaders have so much to do, and could do it, it is sobering that so few, relatively speaking, are willing to compel them to do so. The people do, after all, have the power. Have they really just given up?

Perhaps not, after all. If it is incontrovertible that South Africans are spurning the ‘democratic electoral process’ for its delivery failure, could it be because they’ve discovered that the democratic electoral process is not actually the deliverer?

We are not, after all, a collapsed society; for all the devastation of bad policy-making, unaddressed historical legacies, and incompetent administration, South Africans are not idling, but getting on with their lives as best they can. It’s not enough, and for most it’s very hard. But we are not imploding.

The sum of the daily efforts of millions – despite regulations that impede them, policies that hamper their enterprise, poorly run schools and ill-conceived labour laws that cruelly narrow their chances, and stolen billions that rob them of better healthcare, policing and reliable transport – could suggest that, for most people, the ‘democratic electoral process’ is not the deliverer, and that what counts for the majority is the amalgam of resources and opportunities they themselves strive to find, create and exploit on their own.

They are neglected by, and indifferent to, formal politics, but theirs is arguably the greater force, the real ‘people’s power’ of individuals making demonstrably better choices for themselves than the democratic electoral process has proved itself capable of.

Just one symbol of it is that sorely misspelled signage offering ‘stumb’ and ‘ruble’ removal.

At a guess, it was written by a man or a woman who might not have much, but does have a will to succeed and the energy and ingenuity to act on it. If policy makers could see this as the wellspring of economic recovery that it is, they would understand the urgent need for reform that is really capable of delivering the liberation promise of 1994.

Michael Morris is head of media at the IRR. This article incorporates elements of Morris’s Business Day column of 20 May.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.