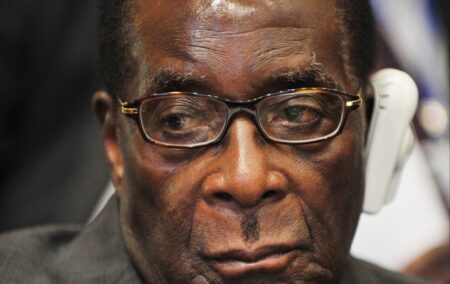

The career of Robert Mugabe makes one thing crystal clear: the international fame and reputation of a black African leader depends entirely on his treatment of white people; how he treats black people is of no consequence.

Mugabe murdered black people in their tens of thousands; he tortured, terrorised and humiliated many more; he caused hunger and starvation among the black working classes; he displaced more black people than Verwoerd; he caused millions of black people to flee Zimbabwe; and he wrecked the economy and brought about 90% unemployment among black Zimbabweans. None of this matters.

The only thing that matters is that he ‘liberated’ Zimbabwe from white minority rule and kicked some white farmers off their lands. This made him a great African hero. This made the African National Congress (ANC) worship him. This guaranteed him standing ovations at forums around the world. Following his death this week, our radio phone-in programmes were full of eulogies for Mugabe – except from Zimbabweans.

After coming to power in 1980, one of Mugabe’s first acts was to begin in 1983 a carefully organised slaughter of Ndebele people in Matabeleland. In the Gukurahundi massacre, over 20 000 black people were murdered, often by the most gruesome methods possible, with the deliberate intention of spreading terror. There are BBC video recordings of black men who witnessed the atrocities of Gukurahundi; they describe how Mugabe’s death squads would move into an Ndebele village, pull out pregnant women, say to each one, ‘You’re carrying the child of a dissident’, rip open her womb and cast the foetus onto a fire.

The outside world found this very boring. The same people who thought that the killing of 69 black people in Sharpeville in South Africa in 1960 by panicking white policemen was a monstrous atrocity just yawned at the cold-blooded slaughter of over 20 000 black people in Zimbabwe.

After Mugabe lost his referendum in 2000, he set about seizing the country’s commercial farms. About 750 000 black farm workers and their families were kicked out of their homes and livelihoods, and forced into destitution. Many were killed, black women were raped. Again, how uninteresting; the outside world said nothing.

In 2005, under Operation Murambatsvina (‘Operation Drive Out Rubbish’), Mugabe kicked over 700 000 black informal dwellers out of their dwellings and into starvation. Once again, silence from the outside world and the ANC.

But in 2000, Mugabe began to kick white farmers off their lands (most of them bought under his government). About 20 white farmers were killed. This was different! White people! People who matter! Instantly, it became headlines around the world and Mugabe became an even greater liberation hero. The ANC was ecstatic and gave Mugabe the most rapturous acclaim ever. There were editorials that began, ‘Well, of course, it is unfortunate that these white people were killed but ….’ Then followed drooling condemnations of these terribly interesting, terribly wicked white people who were really to blame for everything.

After that, the economy collapsed, Zimbabwe changed from a food exporter to a food importer, and ordinary black people starved or emigrated, while Mugabe’s cronies drove shining new limousines and lived in mansions. (Mugabe himself, who always tried to dress like an English gentleman and who despised everything African while worshipping everything European, always took to the road in a fleet of gleaming Mercedes vehicles with armed motorcycle outriders and wailing sirens. In contrast, his predecessor, Ian Smith, moved around in an old Peugeot with one chauffeur.) Leaders of the ruling Zanu party sent their children to private schools in Europe with white teachers.

I first went to Rhodesia in 1969. I was in final year physics at UCT and rode up on my motorbike (a 1960 BMW R50). I hated the regime of Ian Smith but was captivated by the country. The scenery was wonderful; my visit to the Victoria Falls by moonlight was the most haunting and beautiful experience of my life. The game reserves were wonderful. The people, black and white, were delightful: friendly, industrious, well-educated and peaceful (despite the civil war then in progress). The soil and climate combined to make the landscape very fertile – much more than South Africa’s. Everything, including electricity, small industry, farming, roads and railways, shops and services, worked well. On my return, I spoke to a Rhodesian fellow student, who said: ‘Andrew, mark my words, when this mess (Smith’s UDI) is sorted out, you’ll see our country boom as no country has ever boomed before.’ I believed him. I had seen the massive potential for prosperity and success.

Now all is in ruins. Robert Mugabe has wrecked Zimbabwe. He has also demonstrated his complete contempt for ordinary African people, whom he treated worse than a medieval lord treated his serfs. The chosen place of his death is fitting: a hospital in Singapore. He was far too superior to be treated by black doctors in Africa. The shocking fact is that life for black people under Ian Smith was better than it became under Robert Mugabe. Under Smith, ordinary black people did not flee the country; under Mugabe, millions did.

Julius Malema venerates Mugabe, and wishes to copy his policies here. Because of pressure from Malema, Cyril Ramaphosa has adopted Mugabe’s policy of taking over white-owned lands. He calls it ‘Expropriation without Compensation’. When Mugabe was under political pressure, he took the proven path of attacking the whites, and it turned him into a revolutionary hero. As South Africa’s economy fails and political unrest grows, will the ANC, following its mission of the National Democratic Revolution, decide to take Mugabe’s path to heroism?

Andrew Kenny is a writer, an engineer and a classical liberal.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the IRR.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.