So goes a popular German expression, literally translated as ‘we speak of God and the World’. It means to discuss a limitless range of issues seeking to discern their meaning.

It was a phrase appropriated for the title of a long-running news and documentary television series. And in its reference to both the esoteric and pragmatic, it is a uniquely appropriate frame to understand a suite of recent developments.

These matters ignited a blazing controversy, about the nature of freedom, about expression and about the exercise of religion. They challenge us to think about how we as members of a society and as citizens – as social and political beings – interact with one another. For liberals, these are matters of grave normative and practical importance.

Richard’s Bay, Monday, 21 October 2019

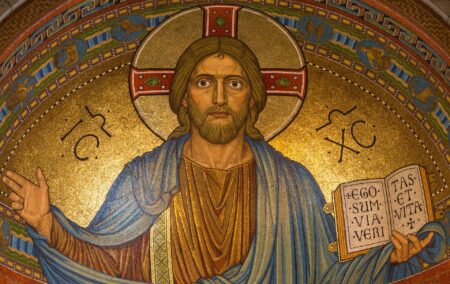

The story begins at Grantleigh School (part of the Curro group) in Richard’s Bay. On the evening of Monday, 21 October, an online video of an irate parent and an art display attracted widespread attention, on both conventional media platforms and on social media. Andrew Anderson, a Christian pastor, led viewers on a brief tour of the display, pointing out with disapproval the manner in which it had depicted Jesus Christ and Christianity.

The artwork (in a technical sense, quite impressive) parodied iconic religiously themed art such as The Last Supper and the Creation of Adam, and depicted Christ in the company of various grotesquely ghoulish and comic characters.

His voice choking, Pastor Anderson declared: ‘My god is no clown, my god is God Almighty’. He went on: ‘It broke my heart to see that you allowed this in this school, and I want to encourage parents, and parents to be to come to this school, not to come to this school.’

In an apparent reference to the dark spiritual influences that might infiltrate the school following this display, he warned: ‘If things go wrong from here onward, it is because of what you allowed to be part of the school.’ South Africa, he said, needed to ‘stand up strong against these things’.

The video ‘went viral’ (in the current parlance) with passionate responses both in support and in opposition.

Understandably and unsurprisingly, much of the criticism revolved around the sense that Pastor Anderson’s position implied a demand for respect, and in so doing, demanding an abridgement of the freedoms of others. As one Facebook comment summarised it in a set of rhetorical questions: ‘Freedom of expression? Freedom of belief?’

This is a concern that should speak clearly to us as liberals, since in the liberal worldview, freedom occupies a prominent and privileged place – and never more so than when the rights to hold opinions, to conscience and to express one’s views are at stake. The words of Danish scholar Dr Rikke Frank Jørgensen are hard to better in setting this out:

Freedom of expression is a fundamental human right that draws on values of personal autonomy and democracy. It is closely connected to freedom of thought and is a precondition for individuals’ self-expression and self-fulfilment. The European Court of Human Rights has described freedom of expression as one of the essential foundations of a democratic society, one of the basic conditions for its progress and for the development of every man. Since the ideas put forward during the Enlightenment, freedom of expression has been one of the fundamental human rights, and it has taken its place in all major international instruments protecting human rights.

We compromise this at our peril. For we hold as axiomatic that freedom to receive and impart information provides space to test and scrutinise ideas, which is necessary for learning. It is an important spur for creativity, and as a consequence, for progress. It enables us to challenge wrongdoing. It is a key dimension of what it means to act as a citizen – a member of a political community with agency – and not merely as a subject of a political authority.

That this controversy was taking place in relation to religion can only heighten the sense that something meaningful and significant was at issue. Religion has historically been a key marker of personal and communal identity – and more than that, something that expresses esoteric purposes and deep convictions. The right of people to accept or reject religious doctrines, and to align their life experiences accordingly, is something that is to be held dear, and defended as an inalienable right of each individual. And just as liberals value human freedom from overbearing state authority, so too are we cautious about the power of religious authorities.

Yet, religious belief is a feature of human life. For millions upon millions of people across the globe, it is an enriching and ennobling experience that affords them a sense of meaning like no other. There is no shortage of people of a generally liberal bent who hold religious beliefs. To reconcile the simultaneous oppressive potential and spiritual satisfaction that religion offers, we recognise the right of each person to decide on whether or not to hold a given set of beliefs, and – in conjunction with voluntarily constituted religious communities – whether or not to participate in formal religious life.

We trust to freedom, then, both because it is right and because it is pragmatic. And it is a seminal achievement of the liberal worldview that the importance of these freedoms has been accepted well beyond the community of self-described liberals.

Pushing back against the pastor…

The sight of a pastor attacking a school art project was instinctively jarring. Many who watched this video this would have read into it a holier-than-thou intolerance, a reactionary backlash against critical self-expression, an attempt to shut down dissenting views.

Other critics asserted that there was a demand for the Christian religion to be respected. The latter point was given credence by a statement from the African Christian Democratic Party, which said in part: ‘It is important that freedom of expression, which includes freedom of artistic creativity, must be balanced against the right of Christians to have their faith respected, as contained in the right to freedom of religion.’

All of this is problematic. As has been repeatedly noted, there is certainly no constitutional or legal right for one’s religion to be respected. It simply does not exist. Quite the contrary: there is extensive precedent for religion (Christianity probably more than most) being criticised, lampooned and ridiculed in South Africa. Forget Zapiro; no one less than Jacob Zuma, then the sitting president, blamed Christianity for many of the country’s woes. Thabo Mbeki referred to it obliquely as a ‘foreign religion’.

There is a growing chorus of opinion that simply dislikes religion (some of it specifically focused Christianity). The writings of the so-called ‘new atheism’ movement is readily available in bookstores, and its views are echoed by many high-powered thinkers in the country. Actually, I’m quite friendly with a couple of them. (As an aside: at different times I’ve been called stupid for holding religious beliefs, and been asked how someone as intelligent – allegedly – as I am could hold them…)

The argument for respect is a fallacy, and the language of rights attending it is absurd. Neither is there a moral right to do so. Respect is either earned or freely given. It cannot be mandated or demanded. The form of respect may be compelled – via laws, for instance – but that produces no more than an appearance. It does nothing to alter inner convictions, and if anything, it uses fear to tuck them away. It is the stuff of totalitarianism, and certainly not something that liberals should entertain.

In any event, if religion is to be free, it implies a proliferation of assertions about the nature of the divine, generally arational in nature (and hence, empirically unsubstantiatable) and in many cases in flat contradiction to one another. There are any number of instances in which fealty to one belief necessarily rejects as wrong, and even malign, the teachings of another. It is difficult to see how respect can exist among them.

And if we are indeed sincere about the value of freedom, we must allow these issues – in all their gaudy, disjointed, discomforting and contradictory glory – to be aired. Free expression, even where it hurts, underwrites free religion.

So we should stand foursquare against Pastor Anderson, right? No so fast. Watching the video, it is clear that he wanted the display gone. But he undertook no act of violence or destruction. He made no obvious threat to the school or to the artist. He expressed his views, explained his position and called for protest and boycott.

In doing so, he was acting entirely within his own rights as a citizen. He was, as we liberals like to put, countering bad speech (as he saw it) with more speech. If we are to stand for freedom of belief and expression as a good in itself, this must be extended to all, including (particularly?) where we might disagree with the perspective.

Indeed, boycotts and protests have a long and venerable place in political activism. They are a freedom-compatible alternative to violent coercion, conveying a message: we assert our legal and moral rights – we use our freedom – to object to your conduct and we voluntarily withdraw our support from you. The teenage Swedish environmental activist, Greta Thunberg, developed her following by doing just this. Whether he realises this or not – and whether or not his detractors do – freedom offers Pastor Anderson a space within which to push his concerns.

What has perhaps not received the attention it deserves is that this took place within a very distinct institutional space. Grantleigh bills itself as having a Christian character. ‘Our ethos,’ its High School flyer proclaimed, ‘is governed by Christian values (ethics and morals) where learners are encouraged to explore and express their individuality within acceptable boundaries, and ultimately take responsibility for their actions.’ Its motto is ‘To God be the Glory’.

If I as an outsider were to ascribe Pastor Anderson’s reaction to anything, one factor would have to be the sense that he had been betrayed by an institution to which he had entrusted his children’s education and with which he had had a hitherto positive relationship. By displaying this art, in his mind, it had repudiated its commitment to upholding Christian ethics, to honouring God, and had allowed one of its talented learners to stray outside ‘acceptable boundaries’.

This response too is not unreasonable, and another that liberals might understand on principle. For we recognise the importance of allowing people to associate freely in voluntary organisations, and to set their internal rules. This is the essence of civil society, groups operating distinctly from both the economy and state – from comedy clubs to think tanks – which is another indispensable element in maintaining a free society. The right to a free, private domain should be jealously guarded. (We at the Institute of Race Relations count as one of our most important achievements in the post-1994 period the defeat of the so-called ‘NGO Bill’, which would have established enormously intrusive powers for government over such bodies.)

Accepting this, we should be neither surprised nor concerned when there is contestation within such institutions. We on the outside have, of course, an interest in how they are resolved, and every right to express our views on them. But as a matter of principle, we must respect the rights of private organisations to manage their own affairs.

Indeed, where this case does raise concerns is in the approach of certain politicians. Dr Imran Keeka of the Democratic Alliance called for an official investigation of the matter – freedom of expression, he reminded us, was not unlimited. Kwazi Mshengu, KwaZulu-Natal MEC, for education said on television news that the constitution protects all religions other than Satanism, although it would be difficult for him to justify this.

No doubt, both of these sentiments would find support among much of the public. But be careful what you wish for: inviting the State to intervene in private institutions is a perilous game, and the influence it may enable could be insidious indeed. Christians who might be tempted to welcome it in these circumstances might think very differently if such a precedent were invoked down the line to examine the soteriology taught in Christian schools, and the offence it gives to their Muslim and Jewish neighbours…

None of this is necessarily to say that Pastor Anderson’s views are to be endorsed, merely that they should be seen in perspective. Is there a threat to freedom there? Perhaps there is. Any restriction of any freedom has the potential to set a precedent that others may seek to exploit. There is also a strong argument to be made for allowing more rather than less latitude to young people to develop their talents and intellect. And as a rule, we liberals would argue that when faced with the choice, the preference should be for more rather than less freedom.

A problem deeper than a controversy?

Yet this controversy seems to have been premised largely on the assumption that Pastor Anderson posed – or embodied – a clear and present threat to freedom in South Africa. As one online comment put it: ‘Religion as practiced by the pastor who publicly (and it seems virally) howled, growled and wept in outrage at this young person’s graphic expression of his thoughts, questions and ideas, surely represents the most profound threat to freedom of thought and expression.’

I’m not so sure. For the reasons set out above, this reading is questionable.

But what this might fruitfully prompt us to do is to reflect on some of the threats to our freedoms that have entrenched themselves, often with surprisingly little challenge. Sometimes to great acclaim.

The most important of these is the assumption that freedom is indeed a universal aspiration. That is implied in that Facebook comment: ‘Freedom of expression? Freedom of belief?’

True enough, as a political concept, freedom retains a great deal of moral power – who, after all, would champion being ‘unfree’? – but it is useful to interrogate what that means.

A couple of years ago, I wrote a piece entitled ‘Drawing a line through free speech’. In it, I drew attention to the preoccupation that many activists have today with the question of ‘where do we draw the line’. Where once activists for civil liberties – and here we’re talking about free societies, democracies – would advocate pushing boundaries and challenging ideas, a new generation seems to have taken the opposite view. Here, the project is to define the limits of the acceptable, to establish narratives within which certain ideas are to be vigorously expressed, while others are expressly shunned.

Interestingly enough, much of this drive revolves around issues connected with religious or other sectarian identity. My own piece centred on the disinviting of prominent evolutionary biologist and doyen of the ‘new atheist’ movement, Richard Dawkins, from an event hosted by a radio station based in Berkeley, Calfornia. The station in question, KPFA, described itself as committed to cultural diversity and pluralistic debate, to fostering understanding among people and to promoting ‘freedom of the press and (serving) as a forum for various viewpoints’. Despite this, it terminated the invite to Dawkins on the basis that he had expressed some unkind words about Islam some years previously: that it was the greatest force for evil in the world. KPFA declared itself unable to host Dawkins based on the hurt he had inflicted. It went on: ‘While KPFA emphatically supports serious free speech, we do not support abusive speech.’

This was an example of an understanding of free speech that restricts rather than expands. What, after all, is ‘serious free speech’? And why should his comments on Islam have disqualified him from discussing an acclaimed book on science – especially when he is in any event known as much for a general hostility to religion as he is for his scientific work.

One cannot help seeing in this an echo of the ‘respect’ argument for which Pastor Anderson and his defenders were attacked. They may have wanted the artist or the school to defer to their standards of religious sensitivity – while KPFA was unwilling to host a speaker for expressing a disrespectful opinion. And it is notable that scepticism of free expression was not being pushed in the latter instance by a (conservative?) Christian pastor, but by an eminently progressive, secular media outlet, based in a community with a consummately ‘progressive’ reputation.

This is a phenomenon that bears thinking about, for it demonstrates that threats to freedom can come from just about any ideological quarter. The academics, student activists and ‘progressive’ politicians who now argue for ‘drawing the line’, are the sorts who a generation or two back, might have energetically pushed that line back. (In the mid-1960s, the left-leaning protest movement at the University of California in Berkeley chose to style itself the ‘Free Speech Movement’.) And the constriction of these freedoms are not phrased in a language of rejecting rights and liberties, but of fortifying them.

Readers might, for example, be familiar with the on-air exchange in early 2018 between the Canadian academic and Youtube personality, Dr Jordan Peterson, and British journalist Cathy Newman. ‘Why,’ said Ms Newman, ‘should your right to freedom of speech trump a trans person’s right not to be offended?’ A very revealing statement, asserting avoiding offence as a ‘right’ on a par with free speech.

This is not unusual. John Whitehead, constitutional lawyer and president of the Rutherford Institute in the United States, has called attention to the manner in which sensitivities, rather than law and a respect for the robust exchange of ideas, have begun to make their way into legal decisions. Referring to the case of Nurre v. Whitehead – which, coincidentally, had to do with a school wishing to prevent ‘offence’ by removing religiously-themed music from a recital – he wrote:

We are witnessing the emergence of an unstated yet court-sanctioned right, one that makes no appearance in the Constitution and yet seems to trump the First Amendment at every turn: the right to not be offended. Yet there is no way to completely avoid giving offense. At some time or other, someone is going to take offense at something someone else says or does. It’s inevitable. Each time we allow political correctness to triumph over our constitutional freedoms and basic common sense, we are complicit in undermining the freedoms on which this nation was built.

In short, it is by no means clear that freedom of expression, freedom of religion – or for that matter any number of other freedoms – is regarded as universally desirable, or that a rhetorical commitment to freedom necessarily means an expansive understanding of it. Indeed, it is not difficult to find academic and popular comment online that pretty much dismisses the importance of free speech, and that censorship is necessary. There is, the argument goes, too dominant an influence by corporate interests/right wingers, a wave of fake news and a veritable tsunami of racist/sexist/Islamphobic/homophobic abuse. Freedom can be a dangerous thing. Once again, let it be emphasised that this is not from a ‘reactionary’, but from an eminently ‘progressive’, perspective. These arguments are carried on more-or-less respectable platforms, such as the Huffington Post.

Nor is this unknown to South Africa. There is a thread in our political culture that sees freedom as dispensable, or subject to the imperatives of higher priorities. In 1986, Conor Cruise O’Brien – an Irish statesman, socialist and no friend of the apartheid government – was prevented from speaking at the University of Cape Town, having derided as ‘Mickey Mouse stuff’ the academic boycott of South African universities. Writer and academic Ampie Coetsee responded thus:

There is no freedom in this country, we have to fight for it, and to attain it we have to accept that certain voices have to be silenced. One day in the future, perhaps, there can be talk of freedom of speech. But at a time of transition it is necessary to prevent those who are trying to block the forces of change – even if that action be considered a censorship.

The sentiments here are remarkable, not least because they were articulated by a writer with deep appreciation for the meaning of words. They not only justify shutting down dissenting voices as an expedient; ‘one day, perhaps’ it will be possible to ‘talk of freedom of speech’. No guarantees. It may or may not be the way we go as a society. This was – to quote the Professor – a struggle for ‘freedom’ that was under way. ‘Freedom’ and ‘free speech’, in this perspective, were not necessarily connected to each other. Words and meanings matter, and the liberal conception of these things is not the only one, or indeed the desired one.

We should remember that activists have their own goals. They may often find freedom inconvenient, if not offensive.

Post-apartheid South Africa has generally provided a good, if far from perfect, environment for civic freedoms. But there have been grounds for concern. One thinks of the investigation by the South African Human Rights Commission into racism in the media. Or the Secrecy Bill. Or the response to Brett Murray’s painting The Spear. Or the University of Cape Town’s rescinding an invitation to Flemming Rose, the Danish journalist whose paper caused a worldwide stir by publishing cartoons in 2005 of the Muslim prophet Mohammed. Then UCT Vice Chancellor Max Price justified this by warning that Rose being on a podium might disturb campus peace and that it might ‘retard rather than advance academic freedom on campus’. In other words, hosting a controversial newsman to discuss a contentious issue could prove cataclysmic to an institution dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge and understanding.

Perhaps the underappreciated apogee in respect of free speech was in May 2010, when the Mail and Guardian – South Africa’s edgy, provocative, intellectual paper-of-choice – carried its own cartoon of Mohammed. Such depictions are a sensitive and controversial matter within Islam, and South Africa may have forgotten just how loud the outcry was at the time; by comparison, it drowned out the Grantleigh furore. Not only had it been foreshadowed by an attempt by the Council of Muslim Theologians to interdict the paper from publishing the cartoon, it sparked a furious blaze of public commentary, and it earned the newspaper threats of violence.

Initially, the Mail and Guardian held its ground. Its editor at the time, Nic Dawes, declared the paper a ‘platform for debate’, and denied that the cartoon was racist or Islamophobic, or that it constituted ‘hate speech’. He even obliquely stood up for the principle that media should be able to offend. ‘If we had to pull every Zapiro cartoon that offended someone we wouldn’t have any Zapiro cartoons in the newspaper,’ he admonished.

Within a week, the tune had changed. Following a meeting with representatives of the Muslim community, the paper undertook not to publish any other depictions of Mohammed until a ‘consultation’ process had been undertaken. (I’m not sure what became of that, to be honest.)

Dawes himself penned a confusing piece. He apologised for the offence that had been caused, that his intentions had been honourable and that Muslims had every right to be angry, perhaps less with his paper than with their position in the world. He declared that his ‘register’ was ‘secular’, which allowed him to understand the political side of the controversy. He then went on to discuss the theological side, which seemed to be aimed at showing that in some sense at least, his actions were not really a violation of Islamic law (or, maybe, that with the help a smart Islamic jurist, he might be able to argue that). And he concluded with a stump for the Mail and Guardian: ‘I can’t imagine a better home for either cartoonist, a newspaper editor, or indeed for the devotees of an extraordinary prophet.’

This has the hum of sophistry about it. There is something rather incongruous about declaring one’s ‘register’ to be ‘secular’, and then measuring one’s actions within the framework of religious law. There is certainly no logic to declaring oneself a ‘non-believer’ and one’s ‘register’ as ‘secular’ before referring to a ‘remarkable prophet’. But to accept the idea of Mohammed as a prophet implies accepting the religious doctrine that holds him to be such, and to accept the message that he conveyed. To reject this – to maintain the ‘secular’ ‘register’ – is to believe that he was not a prophet at all (and probably that prophets are an entirely mythical concept), and quite possibly something worse. It made no sense. Personally, I found it rather patronising.

And however he may have chosen to present it, there is no escaping that Dawes was willing to give up a part of his newspaper’s prerogative to publish to mollify the religious sentiments of his critics. There isn’t a great deal to distinguish what he in fact did, and the supposed danger that Pastor Anderson and his demands posed.

And then, of course, there was the notorious ‘flag issue’. Still fresh in the public mind, it requires little explanation, except to note that the courts have banned the display of an object, even within essentially private spaces. That should provoke some concern, no matter how offensive one may find the pre-democracy flag itself. But the fact that the ban was greeted with near universal support by the media, with no objections for the dangerous precedent this might set, or for the principles that a ban would ride underfoot. It was rather as if many were determined to be part of a moral-ideological moment of catharsis, wherever that might lead.

We could well say that their professional backgrounds should make editors and journalists more cautious of intrusions into the freedom so necessary for their work. That they failed to see that this should concern us more than the words of a hitherto little-known Pastor.

And so…

We imbibe much of our experience of the world through popular culture, and from time to time something intended entirely as entertainment can convey important truths. In the Star Wars movie Revenge of the Sith, Padmé Amadala greets the announcement of the establishment of the Galactic Empire with the comment: ‘So this is how liberty dies … with thunderous applause’.

This is true. Too often we as a society misunderstand threats as they emerge, we engage them selectively and without reference to principle, but rather because they tickle a particular sentiment. And too often those who should know better choose not to.

Jordan Peterson, in responding to Cathy Newman’s challenge about the ‘right’ not be offended, put forward a powerful thought: ‘In order to be able to think, you have to risk being offensive. I mean, look at the conversation we’re having right now. You’re certainly willing to risk offending me in the pursuit of truth. Why should you have the right to do that? It’s been rather uncomfortable … You’re doing what you should do, which is digging a bit to see what the hell is going on. That is what you should do. But you’re exercising your freedom of speech to certainly risk offending me. And that’s fine. I think more power to you, as far as I’m concerned.’

Freedom is difficult. It is uncomfortable. None of us is a one-dimensional being, and cleaving hard to principle is tough. And in a dynamic world, this is a high-stakes game. Difficult as it is, it is a path worth travelling.

Postscript: An apology was issued by Curro for the ‘offence’ caused, and the display was taken down. Pastor Anderson said: ‘I think it’s from all the pressure, and all the unity of the Christian people sticking together, for these things to come down.’ Liberals may well feel uncomfortable with this outcome – it is no victory for free speech and at best an ambiguous one for the free exercise of religion. Yet there is some consolation in noting that this was due to the activism of ordinary people, not the diktat of the state.

The aspiring artist – eventually identified in the media as Gary Louw, one of the school’s top achievers – has said that his art was really about the ‘commercialisation of contemporary religion as well as the monetary exploitation of the faithful by greedy individuals who hide behind the guise of the church or similar pious institutions.’ He said that he had expected that there would be ‘some people who would be offended.’ He also indicated that he had been approached by people wanting to buy his work; he confirms that he will continue with his art.

Both Pastor Anderson and Gary Lou are part of South Africa, and each in his own way, they have made use of the freedoms available to its people. This is no bad thing.

Meanwhile, with some symmetry, on the day Pastor Anderson came to prominence in South Africa, a number of wooden carvings were stolen from the Church of Santa Maria in Traspontina in Rome. These were at the centre of a row in the Roman Catholic Church, which was holding a synod of bishops from the Amazon region. Depicting pregnant women with an Amazonian appearance, it was unclear what these carvings were intended to represent: the Virgin Mary, an undefined symbol of life (Paolo Ruffini, Vatican communications head, described them as ‘life, fertility, mother earth’), or a pagan deity…

These images are a matter of profound importance to many of the Catholic faithful, as the objects were used in what appeared to be acts of worship, most visibly in a ritual in the Vatican Gardens in which a group of people prostrated themselves before the statues.

The perpetrators of the theft recorded their actions, which culminated in the carvings being thrown into the River Tiber. A statement later appeared in which they said that they had acted in defence of their faith and out of concern for the souls of those who might be led astray by the false spirituality these statues represented: ‘Because we love humanity, we cannot accept that people of a certain region should not get baptized and therefore are being denied entrance into heaven. It is our duty to follow the words of God, like our holy Mother did. There is not a second way of salvation.’

These are hard words and even harder actions. They are also probably the words of very sincere faith. They have been harshly attacked. And they signify the stresses playing out within one of the world’s largest and oldest religious communities – an internationalised version of what happened at Grantleigh school.

Whether in Richard’s Bay or Rome, these are issues that will not soon disappear.