The story of China’s escape from poverty is remarkable, both for the outcomes achieved, and for the reforms that produced them.

China’s achievements are generally agreed on. We know from World Bank data that the proportion of people living in extreme poverty (income less than $1.90 per day) declined from 66% in 1990 to less than 1% by 2015. Using the poverty level of income of $1.25 a day, the bank calculates that the incidence of poverty in China declined from 85% in 1981 to 27% in 2004.

But the question of which reforms led to these happy outcomes is not uncontested. Those who support greater state control of the economy will point to Chinese state-owned companies and Chinese regulations restricting such things as the kind of businesses foreigners can open in China (reforms to lessen these restrictions are ongoing). The problem, of course, is that China before the 1978 3rd plenary session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party had an economy that was almost entirely controlled by the government.

Chinese land under the control of peasant farmers was subject to collectivisation and many of these farmers died simply because they could not sell their produce on the open market and were forced to produce according to government quotas. All industry was controlled from Beijing, with no space for private ownership. Import tariffs were set at a high level in order to ‘protect’ the domestic Chinese economy. All of this led to untold suffering and starvation.

“It doesn’t matter whether a cat is black or white, as long as it catches mice.”

Deng Xiaoping

Deng’s famous aphorism, uttered at a 1962 Communist Youth League conference, has come to symbolise the spirit of the Chinese economic reforms initiated under his leadership. The Chinese reforms marked a change in thinking for the Communist Party from being motivated primarily by ideological concerns towards an empirical approach that prioritised economic production, no matter how it was achieved.

Policy reform that is led by poor people

Most casual observers of China would have missed the fact that some of the reforms from the 1978 plenary, specifically the introduction of the household responsibility system, were simply a result of policy-makers taking their lead from what Chinese citizens had started doing illegally in order to survive. Under the Cultural Revolution, Chinese peasant farmers had faced starvation and so they started selling produce, over and above the government quota, on the black market. The household responsibility system formalised this by making families responsible for their own production, for losses as well as any profits.

African countries, with their large and dynamic informal sectors, could learn from this model of bottom-up reform. Such an approach would see African governments seeking to formalise informal trade simply by making legal those things that people were already doing, without requiring anything from the entrepreneur. In South Africa, this might mean legalising Mashonisas (so-called loan sharks, equivalent to medieval European money-lenders, the precursors to modern bankers) without adding any additional regulatory barriers to their industry.

The household responsibility system was later extended to other parts of the Chinese economy, including state-owned companies where managers were made responsible for the profits and losses of the company, and were given the freedom to trade in the open market. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) followed this up by allowing privately owned and run businesses. These two elements served to introduce accountability at two important levels. The first was the individual level, where managers and peasant farmers were no longer working towards government targets and quotas but rather working to meet the needs and wants of Chinese and global citizens through the market, leading to a more efficient economy.

The second was at the level of market competition. That ordinary Chinese could now own businesses meant that state-owned companies faced competition from private citizens.

In fact, economist Fan Gang has noted that, since the reforms, Chinese GDP went from being wholly under government control to the private sector’s making up 70% of GDP as of 2005. It is clear, therefore, that the Chinese miracle has been driven by a revolution in the ownership of the economy, from the government to private hands. This is the lesson from the Chinese miracle that Africa so badly needs in meeting the challenge of getting Africans out of poverty.

This is not to say that government should not provide a social safety net and services such as education and healthcare. It simply means, as in the case of Scandinavia, that governments should allow those who are willing and able to produce to do so. There is no more efficient means of finding these producers than a free market in which individuals are allowed to own property and businesses.

“There are no fundamental contradictions between a socialist system and a market economy.”

Deng Xiaoping

This quote comes from a Time magazine interview of 1985. It is less well-known, but it nonetheless serves to illustrate the thinking behind the reforms implemented under Deng’s leadership. Simply put, the emphasis in China was on maximising production in order to enable and then sustain the state’s redistributionist goals. This means a government being willing to let markets do their thing while simultaneously using the ever-increasing tax revenue to improve the lot of the worse-off in society.

The benefits of free markets

There’s little doubt that market economies are the most productive economies. The Fraser Institute’s index of economic freedom produces a score for each country by measuring things like the regulatory burden, the rule of law and private property rights protection, the size of government (spending as a share of GDP, the tax burden, transfers to state-owned companies etc), the stability of the currency and the freedom to trade with foreigners. The usefulness of the index lies in its being assembled from objective data (produced by governments and independent organisations, not the compilers of the index), and has been found to correlate with leading developmental indicators.

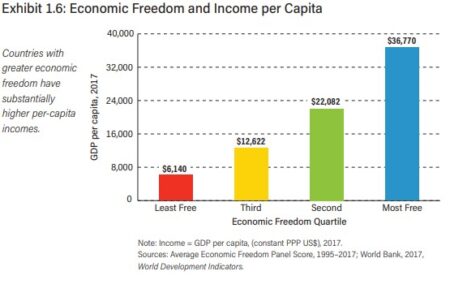

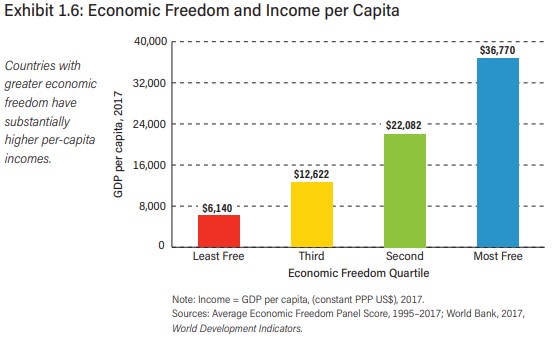

To give an example, the first quartile of the index comprises the 25% most economically free countries in the world, the 2nd quartile the next 25% and so on until the 4th quartile. The average GDP per capita of the most free quartile is $36,770 while the least free quartile has an average GDP per capita of $6,140. That is a difference of $30,670.

Source: Fraser Institute, Economic Freedom of the World Report (2019)

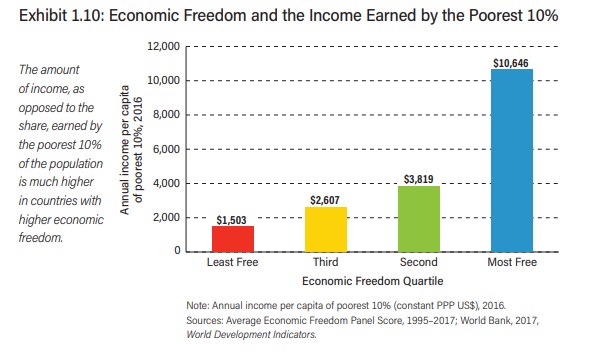

The remarkable thing is that not only is economic freedom a good predictor for average income, it is also a good predictor of the average income earned by the bottom 10% of income earners, and that is relevant in explaining why China has experienced the fastest decline in poverty levels in recorded history.

Source: Fraser Institute, Economic Freedom of the World Report (2019)

If you are among the bottom 10% in a country that is in the top 25% of economically free countries, you will earn an average of $9,143 more than a person in the bottom 10% of income within countries in the least free quartile of economic freedom.

China itself is in the third quartile, ranked 113th in the world. That is an impressive ranking for a communist country. (For comparison, Brazil is ranked 120th, while South Africa is ranked 101st in the world). What is even more impressive, is that Hong Kong which is part of China, is ranked 1st in the world. That is an indication of how well China has implemented its Special Economic Zones (SEZ) policy. Hong Kong can be considered to be the first Chinese SEZ due to the free-market policies implemented by the British and later continued under Chinese administration.

Africa on the other hand only has nine countries in the top two quartiles, with only Mauritius, ranked 9th in the world, in the first quartile.

African countries in the top two quartiles of economic freedom

| Country | Ranking | Quartile |

| Mauritius | 9th | 1st |

| Uganda | 48th | 2nd |

| Botswana | 49th | 2nd |

| Rwanda | 56th | 2nd |

| The Gambia | 60th | 2nd |

| Cape Verde | 63rd | 2nd |

| Seychelles | 63rd | 2nd |

| Kenya | 70th | 2nd |

| Nigeria | 81st | 2nd |

Source: Fraser Institute, Economic Freedom of the World Report (2019)

Perhaps, then, it shouldn’t be a surprise that African countries continue to lag behind the rest of the world when it comes to measures of human development. Productive individuals face regulatory barriers when they try to enter markets. They also, in many cases, do not have the legal certainty provided by secure private property rights. China has gone from being the worst example of this in the world to now being a world leader in terms of economic freedom when it comes to the most free SEZs.

Special Economic Zones: A lesson for Africa

Apart from the CCP allowing itself to be led by ordinary Chinese citizens who ignore rigid ideological constraints, reforms in China have a second distinguishing characteristic: they are based on empirical evidence. This is where the SEZ policy shines. According to the World Bank’s 2015 report, China’s Special Economic Zones: Experience gained, ‘China’s experience with SEZs has developed over time. It began in the early 1980s when market-oriented reforms were introduced in selected SEZ areas such as Shenzhen.’ ”

China’s SEZs have ‘contributed significantly to China’s development. They have permitted experimentation with market-oriented reforms, and acted as a catalyst for efficient allocation of domestic and international resources’, according to the same World Bank document. This demonstrates a commitment to evidence-based policy instead of policies judged primarily by their adherence to ideological principles. The latter is something Africa still struggles with, while China has shaken off ideological constraints in pursuit of a single goal: economic production.

China’s SEZ policy was also part of a package of reforms meant to attract capital from the rest of the world. Some of these reforms involved lowering import tariffs in order, first, to lower import inflation for Chinese consumers and producers, and also to encourage a reciprocal lowering of the tariffs levied on Chinese exporters by other countries. The Chinese government also took credible steps to ensure the security of property rights for foreigners.

As an indication of how far the Chinese reforms went, article 4 of the Chinese Law on Wholly Foreign-Owned Enterprises passed in 1986, guarantees the ‘investments, profits and other legitimate rights and interests of foreign investors in China’. Article 5 of the same law guarantees that the State ‘will not nationalize or expropriate enterprises with sole foreign investment’ except as required by the public interest and always with the payment of compensation. This is a communist government guaranteeing the security of property rights for companies owned by foreigners. This is an example of choosing prosperity (and defeating the poverty afflicting your people) over ideology.

Chinese investment and loans in Africa

The motives behind Chinese investment in Africa are the subject of intense speculation and debate in a way that is not true of investment from Western countries. This seems strange given the continent’s experience of Western colonialism.

This is not to say that African countries should naively assume that Chinese investors have our best interests at heart, but rather to recognise the Chinese appetite for investments in Africa as a potential win-win scenario. The people of this continent have become accustomed to blaming foreign nations for the poor negotiating skills of African politicians and their desire to finance their corrupt activities through foreign debt. It is not China’s fault that African leaders take on debt, not only from China but also the West.

Debt should never be taken on for consumption purposes, but only to finance projects that will yield greater returns than the interest on the debt. Otherwise African countries risk falling into a debt trap where the money is borrowed from Peter to pay Paul.

Indeed, private Chinese investment on the continent is largely motivated by objective economic reality, whereas government-to-government funding is largely motivated by political considerations – such as the Chinese government’s belt and road initiative. These political considerations lead directly to the ‘debt trap’ effect: African governments taking on more debt than they can repay. The lesson should be that trade with China is good, but trade between private Chinese individuals, companies and their African counterparts is even better.

Africa is blessed with more resources than the Chinese have access to. What this continent lacks is an empirical approach to policy-making. If we could learn just that one lesson from China, Africa’s future would be bright, as we could eliminate poverty through free markets and property rights, just as China has done so successfully. But that will require a commitment to empiricism over ideology.

If you like what you have just read, become a Friend of the IRR if you aren’t already one by SMSing your name to 32823 or clicking here. Each SMS costs R1.’ Terms & Conditions Apply.