South Africans are making their own alcohol, and the black market in cigarettes is making outrageous profits. Government says that its reasoning for not permitting tobacco sales is ‘classified’, but ban or no ban, the free market will find ways around it.

The first deaths due to bad homebrew alcohol have been reported: a Northern Cape couple who ‘loved each other dearly’ and died after drinking a bottle of tainted beer each. It seems likely that many more deaths would have occurred, but haven’t attracted media attention.

Although nobody has reported on the extent of the illegal alcohol market, anecdotal evidence suggests that everyone and his dog is either brewing or distilling for their own consumption, and that of their friends.

South Africans are whipping up a wide variety of concoctions, from traditional umqombothi, brewed made from maize meal and sorghum malt, to ginger beer, pineapple beer, apple cider, ordinary craft beer, and distilled liquor more commonly known as witblits.

General Fedora, the chief jackboot of the police, wants nothing more than to extend the alcohol ban in perpetuity. He has cracked down hard on home-brewed beer. Undaunted, however, newspapers and other media have happily been sharing recipes to make your own beer.

There are significant risks with making your own alcoholic drinks. Failure to sterilise brewing vessels and utensils can create the perfect environment for harmful bacteria to grow. Homemade beer also does not last long, before it goes bad. The results can be deadly.

Some people have also started to distil their own liquor, which is even more fraught with danger for the amateur. The science of distillation isn’t trivial. The first alcohol to boil off as the mash is heated up is methanol, also known as wood alcohol, which is toxic and can cause blindness and death. Only once the methanol is gone does the ethanol start to distil off, which is the stuff you want in your drink. Home distillers who don’t control their temperature properly, or fail to discard the early distillate produced before the mash reaches the boiling point of ethanol, risk methanol poisoning.

Entrepreneurial alcohol manufacturing

On Google, interest in terms such as ‘distilling’, ‘witblits’, ‘home brewing’, ‘cider’, ‘homemade beer’ and ‘pineapple beer’ has spiked since the start of the lockdown, suggesting that there’s a lot of, shall we say, entrepreneurial alcohol manufacturing going on in South Africa.

Some have turned to smuggling alcohol from neighbouring countries, or simply looting closed liquor stores.

A few weeks ago, I wrote that prohibitions don’t work, and should be lifted. I noted that Prohibition in the United States, which began 100 years ago this year, did not decrease drinking, increased the health risk to drinkers, increased crime rates, reduced tax revenues, and denied work opportunities to the unemployed.

SA Breweries (SAB), which has appealed to the government to permit alcohol sales under lockdown Level 4, echoed this sentiment. The company’s director of regulatory and public policy, Hellen Ndlovu, told IOL that ‘South Africa has a fully functional illicit alcohol market which is ready to capitalise on any ban implemented’.

The Mail & Guardian reported that black markets in alcohol operate both in the townships and in the suburbs, selling booze for roughly double the pre-lockdown retail prices. The illegal trade has even involved the very police officers charged with stamping it out.

Ndlovu also pointed out the ripple effects of the alcohol ban throughout industry, from glass makers to farmers: ‘SAB’s value chain is wide-reaching and incorporates a total of 3 739 suppliers, of which 1 345 are SMMEs, supporting in excess of 140 000 jobs. In addition, our business sources agricultural inputs from more than 1 277 farmers, of which 757 are emerging farmers.’

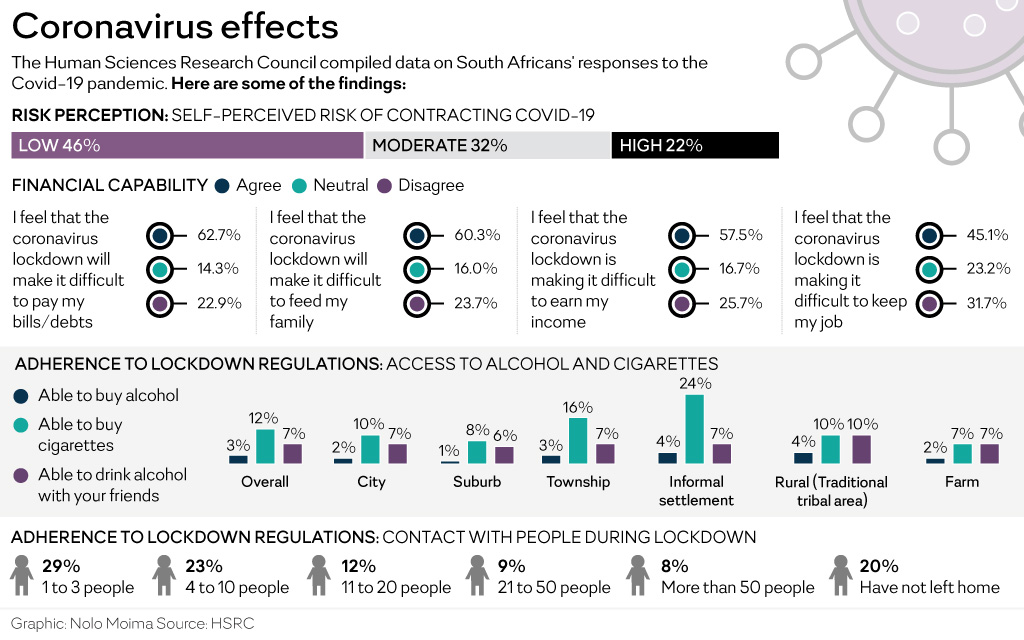

The Daily Dispatch published a graphic based on an HSRC survey conducted in April:

It indicates that very few people admitted to being able to buy alcohol during the lockdown. It seems very likely, however, that survey respondents were loath to admit to buying alcohol illegally. Not only the seller is at risk, but buyers of prohibited products are also guilty of a punishable offence. Moreover, few buyers are likely to jeopardise their own supply by putting their suppliers at risk of arrest.

As more people learn to brew their own beer or distil their own liquor, and discover that they will sell at outrageous prices, it seems only a matter of time before the black market is swollen with the addition of thousands of new suppliers.

The changing branding of litter

Meanwhile, the branding of litter has changed. Where once the pavements were decorated with empty packets of Camel, Dunhill, Peter Stuyvesant, Pall Mall, Kent, and Chesterfield, eight weeks of lockdown has turned up relatively unknown discount brands, such as Remington Gold, Sahawi, Premium International, Savannah, Shasha, Caesar, JFK, Stix, Chicago, Sharp, Voyager, Richman and Derby.

While the cats are away, the mice have come out to play.

The HSRC survey April found that one in four smokers in informal settlements are still able to obtain cigarettes, although suburban smokers seem less enterprising, with only one in twelve saying they can still buy cigarettes.

Chances are that, as with alcohol, many of the survey respondents didn’t admit to the crime of buying cigarettes on the black market. It is likely that far more nicotine addicts are finding ways and means to remain supplied than the HSRC survey suggests.

It took News24 reporters all of four minutes to find cigarettes for sale.

Price of cigarettes nears price of cocaine

In the first weeks of the lockdown, the general rule in the black market was that cigarettes sold for roughly double their pre-lockdown price. Regular brands would go for between R60 and R100 a pack, depending on the brand, while many discount brands sold for R30.

The higher price initially accounted for the increased risk that retailers incurred in breaking lockdown regulations to sell them.

Although it is still possible to get top brands from black market retailers, they are becoming more rare, and nowadays command up to R150 a pack, according to reports from smokers. Discount brands can command as much as R80 per pack these days. Soon, the price of cigarettes will rival the price of cocaine.

This time, the rising price probably indicates that supplies are beginning to run low. Those tobacco companies that replied to questions by News24 journalists Alex Mitchley and Murray Williams have denied selling cigarettes into the market, which, if true, would leave existing stocks at distributors and retailers as the only source for cigarettes. It is implausible to suppose, however, that a black market that can command such rich mark-ups will remain unsupplied for long.

The rise of ‘illicit’ cigarettes

In 2016, three multinationals, British American Tobacco South Africa (BATSA), Japan Tobacco International (JTI) and Phillip Morris International, controlled over 90% of the South African market, predominantly with imported brands manufactured locally under licence.

The rest of the market was supplied by local manufacturing or import companies, such as Carnilinx, Gold Leaf Tobacco, Best Tobacco Company, Amalgamated Tobacco Manufacturers, Pacific Cigarette Company, Protobac, Folha Manufacturers, Afroberg Tobacco Manufacturing and the intriguingly named Home of Cut Rag. Some of these companies are represented by the Fair-trade Independent Tobacco Association (FITA).

These lesser-known brands typically sell at a large discount compared with the better-known brands, and before the lockdown some brands sold at or below the R20 per pack which would account only for the excise duty of R17.40 plus 15% VAT. Given that the R20 threshold doesn’t account for manufacturing or distribution costs, one can safely assume that any cigarettes sold at this price level have not accounted for all the required taxes, and are therefore illicit.

The recently-dissolved Tobacco Institute of South Africa (TISA) represented the multinational majors, and relentlessly campaigned against the illicit cigarette market.

In November 2018 it published a tobacco market study (archive copy), conducted by market research firm Ipsos, which it claims proves that discount brand manufacturers, notably Gold Leaf Tobacco and Best Tobacco Company, were behind a steep rise in the sale of ‘illicit’ cigarettes in South Africa.

It found that the market share of illicit cigarettes (defined as those selling below R20 per pack) was as high as 42% in the informal market, and 33.1% in the overall market.

Gold Leaf’s Remington Gold (RG) brand was the single biggest seller in the market, with 21% of overall market share, narrowly pipping the country’s long-time market leader, Peter Stuyvesant, which lags on 20% share of the market. Two other discount brands make the top ten brands list by market share, namely Savannah, another Gold Leaf product, and Caesar, produced by Best Tobacco.

The industry majors have a long history of exaggerating the size of the illicit market, in the hope of discouraging further excise tax increases, but in recent years, the gap between its estimates of illicit market share and the estimates of academic researchers has closed.

Well-connected smugglers

FITA, which counts both Gold Leaf and Best Tobacco among its members, strongly denied that its members were complicit in selling cigarettes illegally and evading tax. It denounced the report commissioned by TISA as ‘biased’, intended as a smear by Big Tobacco against vigorous competition by lower-priced domestic rivals. It also challenged the removal of some of its members’ brands from major retail outlets on similar grounds.

While its argument about anti-competitive skulduggery is certainly plausible, FITA neglected to explain how it was possible that legal cigarettes could, according to the Ipsos report, be ‘73% cheaper than the reference price in the legal market used by Treasury to determine excise duties, and 44% cheaper than minimum taxes owed on each pack’.

FITA member Carnilinx, run by controversial businessman Adriano Mazzotti, has admitted to smuggling and tax evasion, and had its premises, and the house of its boss, raided by SARS to recover part of an alleged R71.9 million in unpaid taxes.

Mazzotti has also declared that he has donated generously to both the Economic Freedom Fighters and the ANC, that is, to the supporters of the socialist revolution that currently goes under the guise of ‘radical economic transformation’.

There are photographs placing Mazzotti together with the minister for cooperative governance and traditional affairs, Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, who is in charge of the Covid-19 lockdown and is one of the leading anti-tobacco advocates in government.

The Sunday Times believes the second of these photos, also depicting ‘gambling tycoon’ Philip Anastassopoulos, was taken on a trip the two sponsored for Dlamini-Zuma to the UK and Greece, to raise funds for her failed bid to beat Cyril Ramaphosa to the ANC presidency, and ultimately, the presidency of South Africa. At the time, Dlamini-Zuma denied that the photos indicate that she dealt with the people in them.

Reasons for tobacco ban ‘classified’

More recently, the president himself had to explain that the continued ban on tobacco products was not intended to serve anyone’s private interests. We’ll never know, however, because the government also said that the minutes of the meeting at which the decision to permit tobacco sales was reversed could not be released because they are ‘classified’.

Opposition politicians have called this a ‘disgusting cover-up’, and pointed out that whether or not to permit the sale of tobacco products is not a matter of national security.

This paranoid level of secrecy, which seems to apply to all lockdown decisions, certainly does not allay suspicions of corruption and self-dealing.

BATSA had threatened to take the government to court over extending the tobacco ban after Level 5 lockdown restrictions were lifted on 1 May. The announcement by Dlamini-Zuma contradicted an announcement a week earlier that tobacco sales would be permitted, made by the president himself. Since it is unlikely that the facts surrounding the relationship between smoking and Covid-19, if any, had changed during that week, this brings into question the rationality of the about-turn.

In the face of determined government opposition, BATSA has now backed down in favour of secret back-room discussions.

FITA, on the other hand, representing the local discount brands, is continuing with a court challenge against the regulations. The association recently received legal confirmation that it is permitted to manufacture cigarettes for export, but the association has also asked the court to overturn the prohibition on the domestic sale of tobacco products.

The government is opposing the action, black marketeers will be happy to know.

The market sees a ban as inefficient, and routes around it

There is an old saying in internet circles, attributed to John Gilmore in a 1993 Time magazine article, that ‘[t]he Net interprets censorship as damage and routes around it’.

The free market works the same way. It interprets prohibitions, high taxes and burdensome regulations as inefficient, and routes around it.

It seems clear that the black market in tobacco products was doing well and growing handsomely even before the lockdown, thanks to the government’s implementation of the UN Framework on Tobacco Control policy of imposing high excise taxes on tobacco products.

Now that retail prices have quadrupled, thanks to the Covid-19 ban, smuggled cigarettes have become nearly as valuable as illicit drugs, and the smugglers stand to become just as rich as drug barons.

The prohibition on alcohol in the US led to the rise of Al Capone and the mafia. The ‘war on drugs’ led to the rise of vastly wealthy and well-diversified criminal cartels.

Neither resulted in the hoped-for health benefits. Both resulted in increased availability of the prohibited products. Both resulted in unintended consequences, such as toxic dangers to consumer health and higher levels of violent crime.

There is no reason to believe that the continued prohibition of alcohol and tobacco in South Africa will not have exactly the same outcome. From homebrew alcohol to high-priced ‘illicit’ cigarettes, we’re already seeing clear signs of thriving black markets.

The only question now is how long the government wants to let them flourish, before lifting the misguided prohibition.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend