While not entirely unexpected, the speed and extent with which the prohibition on tobacco products has failed is startling. About 90% of surveyed smokers continued to buy cigarettes during the ban, and smokers hardly cut down on their habit at all.

On 27 March, when the National Command Council imposed house arrest on most South Africans, it also prohibited the sale of alcohol and tobacco products, on the grounds that these were not ‘essential products or services’.

Readers who have been following my columns on The Daily Friend will be aware that from the outset I argued that prohibitions do not work, and should be lifted. Last week, I reported that black markets in booze and cigarettes were thriving.

Now, there is independent verification of these claims, at least for tobacco products. Some 90% of the respondents to a survey published last week by researchers from the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP), at the University of Cape Town’s School of Economics, say that they have continued to buy cigarettes since the lockdown began, despite the ban on the sale of tobacco products.

The paper, entitled Lighting up the illicit market: Smoker’s responses to the cigarette sales ban in South Africa and authored by Professor Corné van Walbeek, Samantha Filby and Kirsten van der Zee, surveyed more than 16 000 smokers, and received 12 204 analysable responses. It was conducted between 29 April and 11 May, with results published on 15 May.

Smokers aren’t smoking much less

About 36% of the respondents said they smoked less than before the lockdown, but this was neatly counterbalanced by 33% of the respondents who reported that they smoked more. Daily cigarette consumption increased slightly during the initial lockdown period. During the extension, however, smoking rates returned to levels marginally (but not significantly) lower than before the lockdown. This, the authors suppose, reflects the dynamics of people who prepared for a three-week lockdown by stocking up before the ban, and began to run out when the extension was announced.

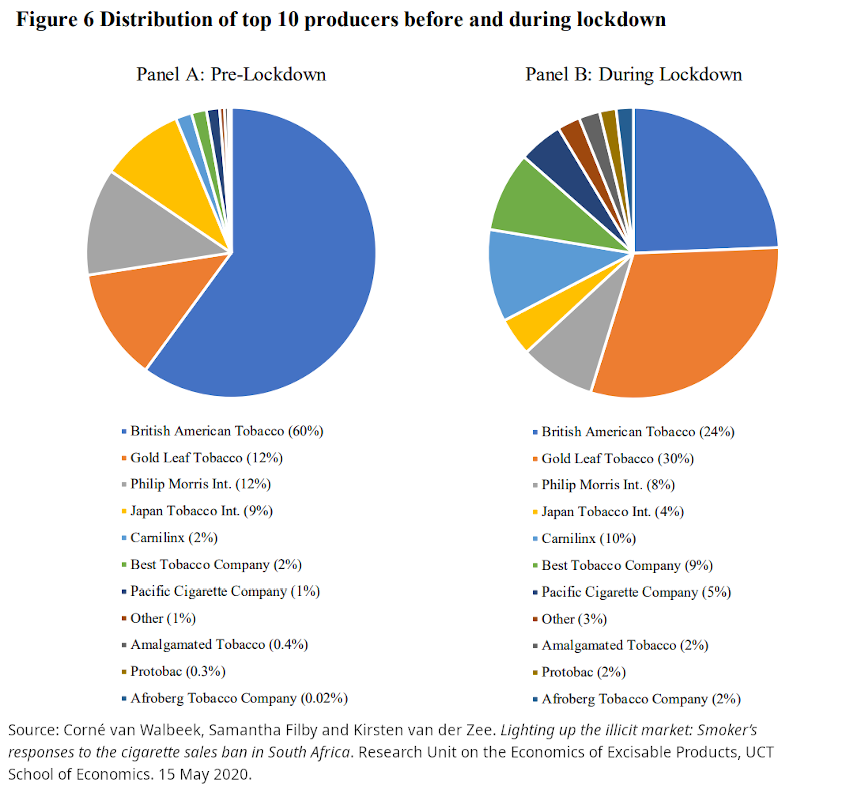

The survey found that many smokers were unable to obtain their usual brand manufactured by one of the large multinational tobacco companies. By necessity, 46% of smokers switched to a brand manufactured by local producers such as Gold Leaf Tobacco Company, Amalgamated Tobacco Company, Carnilinx and Best Tobacco Company.

This, the authors say, has dramatic implications for market shares in the South African cigarette market. Whereas before the lockdown, 81% of respondents smoked multinational brands, only 37% continued to do so after the lockdown.

The researchers report that the retail environment for cigarettes also changed dramatically after the prohibition was imposed. Before the lockdown, 56% of smokers purchased their cigarettes from formal retailers. Only 3% did so after the lockdown. The percentage of smokers who purchased from spaza shops increased from 34% to 44%, and from house shops from 4% to 18%. Sales outlets that either did not exist, or that were inconsequential before the lockdown, but that became important sources of cigarettes during the lockdown include street vendors (26% of smokers), friends and family (30%), WhatsApp groups (11%), and ‘essential worker’ acquaintances (10%).

The high price of a nicotine habit

The price of cigarettes increased steeply during the lockdown. During the course of the survey, a daily price increase of 4.4% was observed. Assuming that this price inflation holds for the entirety of the lockdown, it does not tally with the average price increase of 90% from the pre-lockdown period, as reported by the authors. At 4.4% per day, the increase from pre-lockdown pricing by the end of the survey should have been 594%, and would have topped 900% by the time of this writing. That would coincide with my own anecdotal observation.

The survey does, however, find that price increases varied a lot by where people live and by their own average income. Price increases correlate almost monotonically with income levels, the researchers found. This suggests opportunistic pricing on the part of retailers, who are aware that the competitive options facing customers have been substantially limited.

The Foundation for a Smoke-Free World (FSFW) is a lobby group funded by multinational tobacco maker Philip Morris International, which promotes smokeless tobacco and e-cigarettes as harm-reduction alternatives to combustible tobacco products.

It commissioned a survey conducted by Nielsen in five countries with different approaches to lockdown, namely Italy, India, South Africa, the United Kingdom and the United States. Of these countries, South Africa was the only country to ban tobacco products during the lockdown.

The study also found that smoking behaviour did not change appreciably in any of the countries, including South Africa, despite the ban. In fact, in-home smokers slightly increased their use of tobacco products during the lockdown period.

It also found that two out of three smokers in South Africa are misinformed about the risk of their habit with respect to Covid-19. Only 36.7% correctly answered that it increased their risk of getting seriously ill of Covid-19. The majority either thought that it does not increase risk (35.3%), or that it increases the risk of contracting Covid-19 (38.1%), both of which are false. (Multiple answers were allowed, tipping the total over 100%.)

In fact, as indicated by the scientific studies cited in a previous column, smoking appears to reduce the risk of contracting Covid-19 by about a factor of four, although once a smoker does get sick with Covid-19, smoking doubles the risk of severe illness.

About quitting…

There is one item that looks like good news in both surveys. The FSFW report found that more than half of South African smokers considered quitting, and 37% attempted to do so.

The independent REEP survey confirms this, finding that 41% of respondents tried to quit. Of those, 39% claimed to have succeeded by the time they completed the survey, which represents 16% of all smokers. Of those, 12% intend to start again after the prohibition has been lifted, which leaves around 13% of smokers who, if they can stick with quitting, might have quit as a result of the cigarette ban.

This translates to an extraordinary quitting success rate of 34%.

On the face of it, this might be trumpeted as a policy success, even if the ends did not justify the draconian means.

However, besides the success rate, these numbers are not terribly unusual, and it is extraordinarily unlikely that the 34% success rate will hold up over time. Nearly 70% of smokers routinely say that they want to quit. Every year, more than 50% attempt to do so. Their success rate, however, varies between 5% and 10%. In some countries, success rates have recently spiked as high as 20%. This is largely attributed to the availability of vaping as an alternative.

Even under ordinary circumstances, vaping is strongly discouraged and electronic cigarettes are regulated as if they were tobacco products. During the lockdown, vaping products are entirely prohibited in South Africa, so there is no reason to expect a long-term success rate any higher than, say 10%.

Given that 90% of smokers continued to buy cigarettes during the lockdown, it seems unlikely that high black market prices are a good motivator to quit smoking, either. That also undermines the public health rationale of raising sin taxes, and exposes such taxes as naked extortion from the victims of addiction.

All the tobacco ban appears to have achieved in South Africa is to funnel income from smokers who desperately need money to buy necessities for themselves and their families, to black market operators. This cannot possibly be deemed a policy success.

Smokers are fuming

Perhaps not surprisingly, the REEP study found high levels of anger among smokers, directed at the government. Analysing open-ended comments, two third of which represented black male respondents, the researchers concluded that 77% of them related to anger.

Among the sample comments selected by the researchers, we find these:

‘I am frustrated, angry, short tempered and have to smoke whatever I can get, the latest Ossum, what the hell…’

‘I feel angry, frustrated and irritated most of the time. I did not get the opportunity to stock up as the decision to ban cigarettes were 3 days before my pay day. I didn’t get a choice of my own to stop or continue smoking. My rights were taken away. A decision was made for me…’

‘The continuation of the ban is illogical – everyone is still smoking – just doing it illegally and at great cost while the government loses tax income and criminals make a fortune.’

And quite right they are. The prohibition on the sale of cigarettes has been a spectacular failure. Most smokers continue to smoke, and continue to have access to tobacco products on the black market. Only 16% have managed to quit, at least temporarily, but most of those are likely to resume smoking in the long run.

Prohibition is a go-to policy for authoritarian, moralistic despots, but it is always irrational, and it always fails. It is startling how quickly and comprehensively it has failed in this case. There can be no justification for extending the ban on tobacco products any longer.

The views of the writer are not necessarily the views of the Daily Friend or the IRR

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend