One of the neatest political ripostes of the dying days of apartheid was the graffito that appeared in central Cape Town just hours after police had doused Mass Democratic Movement protesters with purple dye sprayed from a water cannon mounted on an anti-riot vehicle.

The rationale was that stained protesters – who were forced to flee when tear gas was fired into the crowd – could be easily identified, and quickly arrested.

The strategy was doubtful – not least because a lone protester managed to clamber on to the vehicle and redirect the nozzle at the nearby headquarters of the governing National Party. This counted as a symbol of the turning of the tide.

But the choicest slogan of the day was the graffito that read: ‘The Purple Shall Govern’.

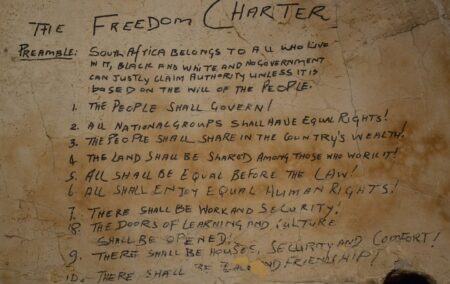

It was, of course, a deft play on the resounding demand – ‘The People Shall Govern!’ – that headed the Freedom Charter, ratified at Kliptown 65 years ago this week.

It came to pass, eventually, and not many years after the later 1989 purple spray affair.

What has remained contentious – and perhaps more intensely so today than at any time since 1994 – is just what is meant by ‘the people’.

It is doubtless foolish to judge the wording of the 65-year-old Freedom Charter on today’s political or cultural terms, but it is telling that it contains evidence of the lasting contradiction in the avowed commitment of the African National Congress (ANC) to ‘non-racialism’.

In its first section, the Charter states plainly enough: ‘The rights of the people shall be the same, regardless of race, colour or sex’.

‘National groups and races’

The heading of the next section, however, alerts the reader to a different order of things: ‘All National Groups Shall Have Equal Rights!’ And here we encounter a sense of a future South Africa society as being made up not of individual citizens, but of ‘national groups and races’.

It states: ‘All national groups shall be protected by law against insults to their race and national pride’, and that ‘(the) preaching and practice of national, race or colour discrimination and contempt shall be a punishable crime’.

Finally, in this section, there is a clause to bear in mind when considering the post-1994 policy landscape: ‘All apartheid laws and practices shall be set aside.’

The ANC’s organisational history reinforces suspicions about the party’s ambivalence about race.

A year after the Liberal Party had chosen to disband in the face of legislation forbidding non-racial parties, the ANC voted at its Morogoro conference in 1969 to allow ‘non-Africans’ to become members as individuals, but only at its 1985 Kabwe conference to allow ‘non-Africans’ to serve on its national executive.

Doubts about the depth, and honesty, of the ruling party’s stated commitment to non-racialism have been lavishly nourished since 1994 by its unashamed reliance on the racial categories defined for it by its unlamented predecessor in government – despite its conviction all the way back in 1955 that all apartheid ‘laws and practices shall be set aside’.

Fundamental to it was the loathed cornerstone of apartheid, the Population Registration Act of 1950, which set out who belonged to which group in quaintly simplistic terms.

‘Generally accepted as a white person’

The Act said ‘“white person” means a person who in appearance obviously is, or who is generally accepted as a white person, but does not include a person who, although in appearance obviously a white person, is generally accepted as a coloured person.’ (Hence the need for pencil tests and other such demeaning expedients). ‘“Coloured person” means a person who is not a white person or a native’, and ‘“native” means a person who in fact is or is generally accepted as a member of any aboriginal race or tribe of Africa’.

On this foundation, the entire edifice was built.

But it didn’t all come crashing down in 1994. (The incremental demolition, in fact, long preceded the election of the ANC in April that year; the Population Registration Act was repealed in 1991, and umpteen other apartheid laws were repealed earlier, between the mid-1980s and 1990).

Came democracy, however, and the question of race was, at best, fudged.

The closest the Constitution comes to dealing with it is a fairly oblique reference to ‘categories of persons’ in the Equality clause in the Bill of Rights.

After stating that ‘(everyone) is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law’, it goes on to say that while equality ‘includes the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms … legislative and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination may be taken’.

‘May not unfairly discriminate’

Some texture is added to what these ‘categories’ are. In setting down that the ‘state [or anyone else] may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone’ on a range of grounds, it says these include (apart from ‘gender, sex, pregnancy, marital status, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth’) not just ‘race’, but also ‘ethnic or social origin’ and ‘colour’.

(Discrimination on one or more of these grounds, the Constitution says, ‘is unfair unless it is established that the discrimination is fair’.)

Post-1994 legislation is more specific about what ‘race’ (or ethnicity and colour) might mean – if without providing any definition.

The Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act, 2002 uses the categories listed in the Constitution (‘race’, ‘ethnic or social origin’ and ‘colour’).

But others – such as the Employment Equity Act, 1998 and the Broad-Based Black Economic Empowerment Act, 2003 – offer the following as a definition: ‘“black people” is a generic term which means Africans, Coloureds and Indians’. (Laws also refer to ‘designated groups’, which might include women, disabled persons or youth.)

Everybody else, presumably, is ‘white’.

If what is meant by these terms is not the definitions of the expunged 70-year-old Population Registration Act, it is not clear what they might be.

These days, making a fuss about it is enough to attract accusations of racism – but only because much of the intelligentsia has caved in.

It wasn’t always so.

Until his death in 2012, one of the sternest and most persistent critics of the ANC’s unblushing adoption of apartheid race categories was former Robben Islander and Marxist academic Neville Alexander.

‘Irresponsible practice’

In a typically unabashed essay of 2006, he rounded on ‘the irresponsible practice on the part of political, cultural and other role models of referring unproblematically to “Blacks”, “Coloureds”, “Indians”, and “Whites” in their normal public discourse, well knowing that by so doing they are perpetuating the racial categories of apartheid South Africa and wittingly or unwittingly entrenching racial prejudice. This discourse is embedded in … legislation … and in the social practices and inter-group dynamics they give rise to or reinforce’.

He went on to make the case for dumping race as a means to measure disadvantage in favour of socio-economic status – which, incidentally, is the measure the government itself uses in delivering grants to millions of people every month, the one non-racial exception in its policy arsenal.

Alexander wrote that ‘there is no need to use the racial categories of the past in order to undertake affirmative action policies’.

The Institute of Race Relations has demonstrated in its Economic Empowerment for the Disadvantaged (EED) proposal how effective this could be.

As Alexander put it, a non-racial empowerment strategy ‘would be equally effective and more precisely targeted at the level of individual beneficiaries if class or income groups were used as the main driving force of the programme’.

‘Technical hocus pocus’

He went on to say that ‘the humiliating experience of racial self-classification and the entire replication of the technical hocus pocus of the apartheid racial ideologues required for the identification of citizens in terms of their “race” would be eliminated’.

‘Instead of subjecting institutional bureaucrats to the thankless task of becoming like their apartheid predecessors, without necessarily using “techniques” such as the “pencil test” or the test of linguistic shibboleths, the monitoring of the required shifts would become a comprehensible and generally acceptable practice.’

Yet, for all the repeated expressions of disquiet among senior government figures, for years now, about the failure and the costs of race-based ‘transformation’, we are not only still lumped with it, but are warned that such measures are to be intensified.

Given the uncertain precepts on which half a century of liberation politics was founded, perhaps it is no surprise that ‘the people’ – or, as President Cyril Ramaphosa is fond of saying, ‘our people’ – are not an indivisible and undivided citizenry so much as a society still riven by ‘race’, exactly as apartheid’s ideologues dreamed it always would be.

[Picture: PHParsons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28581038]

If you like what you have just read, subscribe to the Daily Friend